China, for centuries adopted by Japanese poets and philosophers as their cultural beacon, had become a poor, filthy, confused, and opium-ridden mess, after years of autocratic government. After the death of the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908), little seemed left to unite the nation.1 Internally, ambitious and brutal warlords arose everywhere, each one aiming to become “top dog.” Externally, every swashbuckler country seemed intent on devouring the immense country, whether piecemeal through concessions2 or in a single gulp by colonization. By 1920, every colonialist country had its own extraterritorial heelin China.3

To prevent their country from becoming another “jewel in the crown,”4 many Chinese intellectuals decided to learn how to build a new, modern nation from scratch. It was cheaper to do this in Tokyo than in London or Boston. Although Japan had committed its own political goofs, it was the first Asian country to create a parliament; reform its economic, educational, and cultural systems; and encourage women to become formally educated. And, having confronted and defeated the largest autocracy in the world, Japan was also the place to learn to how mangle Western giants.

By the mid-1920s, more than 10,000 Chinese students and over 1,000 Chinese officials had enrolled in graduate or short-term study courses in Tokyo schools. Moreover, in much of whatever was left of the Chinese government, more than 600 Japanese were functioning as tutor-employees.

Many revolutionaries had cut their teeth in Japanese institutions and joined the Tongmenghui (Chinese United League). These included Sun Yat-sen, the father of modern China; Wang Ching-wei, his successor and head of the Kuomintang political party; warlord Chiang Kai-shek, future head of the Nationalists; and many others. Some of them were also openly financed by Japanese political institutions, industrialists, bankers, or all three.5

In turn, many a Japanese Sinophile had moved to the continent, hoping to help make China the gemstone of a Japanese Commonwealth of Asian Nations. Shocked at the ugly realities of a world of poverty, filth, and disorder, some of those “China-lovers” as they were called, began trying to improve the environment; others, however, became spiteful, oppressive, or exploitative.6 Some moderate-leaning members of the military viewed North China as the buffer against Russian expansionism and a treasure chest of raw materials; and then there were the ultra-conservative warriors who remained intoxicated with their three-decade-old crush of Russia.

One mangled remnant of Japanese feudalism, the ronin,7 were itching to move to China. Idle, penniless, and believing that Japan owed them a living, they began promoting the idea that Japan should conquer and crush China, and divvy up the booty with them.

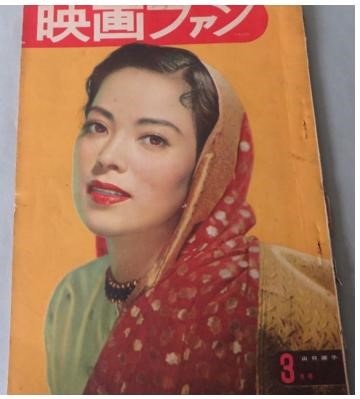

Finally, in the words of the film critic Akira Shimizu: “To Japanese youths of the time, the idea of advancing into the Asian continent held a mesmeric allure similar to the prospect of living in Europe or the United States for the young people today. Li Xianglan was the queen in their dreams, with visions of a colorful rainbow connecting Japan and the continent… The fact that she was Japanese was nothing short of an irony in history.”8

This was the milieu in which Yoshiko/Xianglan’s story would develop.

In the new Manchukuo, the Man’ei Studios were far better equipped than most Western film facilities. Most of the performers and technicians were Chinese, but all the executives were Japanese. Despite the differences in rank and pay, the relations between them were quite cordial.

According to Professor Chia-ning Chang: “Such an extraordinary assortment of strange bedfellows made Manchukuo’s most conspicuous ‘national policy’ organ an ideologically ambiguous, structurally clumsy, hierarchically divided, but nonetheless fascinating product of Japan’s cultural and political imagination.”9 And, one should add, a fabulous place to work.

Curiously, Manchuria’s Higher Police kept a close eye not just on Man’ei’s Chinese workers, but also on the activities of its directors, producers, and executives, disregarding that a good number of them were Japanese intelligence operatives.

Li Xianglan’s success continued unabated, both as a star in Man’ei’sfilms and in the various public events organized to feature her.

In 1944, she discontinued her association with Man’ei and moved to Shanghai to work for Kawakita Nagamasa Film Productions, officiallycreated to expand film production in China. Kawakita was a dedicated worker who sincerely loved the country and its people. By the time WWII ended, Yoshiko had starred in 19 films,10 been showcased in several concerts, and become the treasure of Kawakita Productions—the undisputed queen of Asian movies.

In May 1945, Yoshiko performed at the Shanghai Grand Theatre in a concert entitled “Rhapsody of the Evening Primrose,” another fantastic success. Her childhood friend Liuba suddenly reappeared, which made the event even more enjoyable. Liuba and her father were now working at the Soviet General Consulate in Shanghai; she was the Consulate’s Cultural Affairs Officer. After the concert, the two women renewed their old friendship, although with some caution due to Liuba’s new position.11 As we shall see, Liuba’s reappearance in Yoshiko’s life turned out to be providential.

On August 10, 1945, aware that Japan had surrendered, Li Xianglan went once more to entertain the Japanese troops stationed nearby. The soldiers, however, had been kept ignorant of Japan’s surrender. In that last heart-and-soul performance, Yoshiko couldn’t control her tears, wondering what would happen to those patriotic young folk.

On August 15, Yoshiko was called to the home of the Chief of the Shanghai Army’s Press Division, Lt. Col. Katsumi Shimada, who asked whether she intended to continue appearing as Chinese or preferred to reveal her Japanese nationality. Ending the masquerade would have its consequences, starting with internment in a relocation center in the Japanese concession until she could be repatriated. But remaining Chinese as Li Xianglan meant that she could be tried as a spy for the Japanese, and condemned to death.

“I want to reinstate myself as Japanese,”Yoshiko said.

She first moved to the flat of President Kawakita, who was on a tour. She would be alone because the servants had quit; they were trying to avoid being prosecuted for collaborating with the enemy.

Upon his return, Kawakita met with his Chinese employees and advised them that, if subjected to interrogation, they should say that they were just following orders. Then, he and his Japanese employees were moved to a row house in the Japanese concession. Finally, the Nationalist military decided to try Li Xianglan as a Chinese traitor.

A repellent character claiming to be a military officer approached her, saying that, for a bribe of 5,000 dollars—well, maybe just 3,000—she could go free. But Yoshiko was broke, and trusted neither proponent nor his proposal. Meanwhile, the editor of a Chinese newspaper friendly to the Japanese was planning to escape to the north and join the Chinese communists—would she join him? But the only place she wanted to move was to Japan.

A Chinese general known for his depravity and misfeasance jokingly suggested that she became his consort, which she adamantly refused. Someone else, either in the Nationalist Army’s Secret Service or in one of the gangs assisting it, asked her to spy for the Nationalists in Manchuria. She had never been a spy against the Chinese people, and she wasn’t about to start now.

The newspapers clamored for revenge: a prompt trial followed by her execution. However, her case kept going from one agency to another, until it landed at a formal court hearing attended by six judges and presided over by Chief Justice Ye Degui from the Bureau of Military Administration. The definitive proof of her Japanese citizenship was a copy of her Japanese birth registration, which she was able to obtain through the graces and finagling of her friend Liuba. Yoshiko was reprimanded. She apologized, and was allowed to repatriate.12

During the final inspection before she was to board her repatriation ship, a Chinese Police Officer held her back, certain that the Chinese traitor Li Xianglan was trying to escape to Japan. With the help of Justice Ye, Kawakita again saved the day for her. She finally went home in March of 1946.

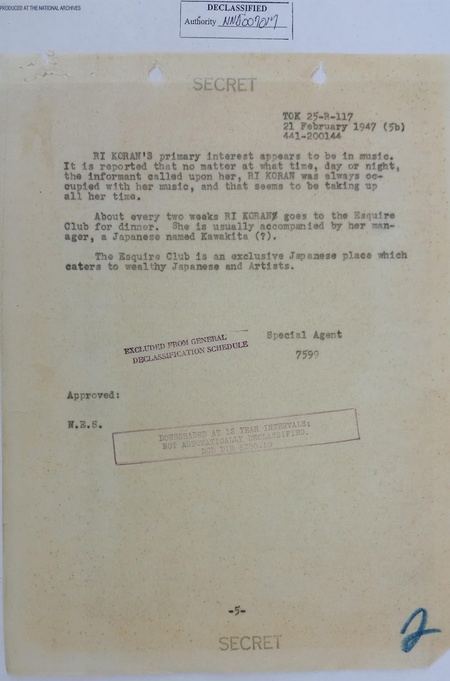

Shortly after debarking in Hakata, she landed on the records of the American intelligence agencies as a person of interest.13

The period after Yoshiko’s return to Japan was quite difficult. She became a vocalist, but the same newspapers that had glorified Li Xianglan just months ago were now chastising Yoshiko Yamaguchi with most unpleasant reviews. She responded by swearing never to make movies again. She then tried the stage, and had a mild success with Tolstoy’s “Resurrection.” Energized by the newspapers’ criticism, she joined a professional theatre group to hone her abilities.

Yoshiko’s family of eight was finally allowed to repatriate from China, after having all their possessions confiscated. Since her family was now penniless, she felt obliged to follow the Japanese tradition that as the oldest daughter, it was her duty to support them. So she broke her pledge and went back to moviemaking. Her first break came in1948, when she won the leading role in The Shining Day of My Life, an anti-war movie. She promptly regained her fame.

In 1950, Yoshiko held recitals in Hawaii, Fresno, and Los Angeles. She also made her Hollywood debut in Japanese War Bride, directed by King Vidor; she was credited as Shirley Yamaguchi.

In 1950, former Japanese Master Spy Yamaga Toru, her “discoverer” for Man’ei films, committed suicide. After the war, he was imprisoned for some time, but escaped when the prison was bombed. He managed to survive for several years in hiding, always afraid of being captured and executed. Unable to get help from anyone, Yamaga and the woman with whom he was living committed suicide together in a remote mountainous area. Several months after the suicide, their remains were found, badly mauled by wild dogs.14

Although this news affected Yoshiko severely, she continued to search for new successes. She would find much of it in an entirely different field: public service.

http://yoshikoyamaguchi.blogspot.com/2015/02/.html.

Notes:

1. Birnbaum, Phyllis, Manchu Princess, Japanese Spy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), 292–93.

2. The ruling GuanxuEmperor, 11th emperor of the Qing dynasty, was conveniently murdered the day before Cixi died; Puyi, her selection for the next emperor, was a weakling full of problems. See Empress Dowager Cixi (accessed 7-9-16).

3. Concessions were territories that China ceded to foreign powers under pressure. Such settlements enjoyed full extraterritorial privileges, including freedom from obeying any Chinese laws.

4. See Concessions in China (accessed 7-5-16).

5. “The jewel in the (British) crown” was a term applied to the British Raj in India for its enormous economical, geographical, and political value to Britain.

6. According to Sun Yat-sen, “Without Japan there would be no China; without China, there would be no Japan.” For an excellent overview of Sun’s relations with Japan, see Jansen, Marius B., The Japanese and Sun Yat-Sen (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1954) and Boyle, John Hunter, China and Japan at War, 1937–1945 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1972).

7. For an excellent post-colonial view of the Sino-Japanese “question,” see Boyd, James, Japanese-Mongolian Relations, 1873–1945 (Kent: Global Oriental, 2011); Harrell, Paula S., Asia for the Asians (Portland, ME: Merwin Asia, 2012); and Kleeman, Faye Yuan, In Transit (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2014).

8. The ronin were vagrant former samurai, readier to fight than to work.

9. In On Actresses: Collected Works on Japanese Film Actors (1980, Joyu-Hen), cited by Yamaguchi, 89.

10. Chang, Chia-ning, Introduction to Fragrant Orchid, pp. xvii-li. Dr. Chang is Professor of Japanese Literature at University of California, Davis.

11. Yoshiko always played the Chinese ingenue who falls in love with a good-hearted Japanese hero and lives happily ever after, despite rigors and troubles. The intent of such propaganda films was to help the Chinese public see the occupying Japanese as their saviors.

12. Eleven years earlier, while the family was still living in Fengtian, the Secret Police discovered that Liuba’s parents, alleged White Russianrefugees, were really active Bolsheviks.

13. In her autobiography, Ms. Yamaguchi details the entire odyssey, regaling the reader with a story that resembles part of a spy novel. See chapter 15, Farewell Li Xianlang, op.cit. 239–56.

14. For a detailed biography of Yoshiko Yamaguchi, see A Biography of Yamaguchi Yoshiko 山口淑子 also known as Li Xiang Lan 李香蘭 (Ri-Koran) (accessed 7/8/16). The blog could easily qualify as the online Yoshiko Yamaguchi museum. It houses an enormous amount of photos, reports, filmed materials, and copies of intelligence agencies’ documents, declassified under newer American laws. This substantial resource was put together by John M. Shubert, and it literally follows Ms. Yamaguchi from birth to death. Readers can review each period of Ms. Yamaguchi’s life in detail.

© 2016 Ed Moreno