On August 2, 1949, legendary Nisei composer and musician Takeshi “Tak” Shindo penned an article for the Rafu Shimpo profiling the rise of a new Nisei musician in the jazz scene: Paul Higaki. Then just 25 years old, Higaki had earned a spot in Lionel Hampton’s orchestra as a top-notch trombone player, and was declared by Shindo to be “the top Nisei trombonist in the country.” To some, he was the one “who made it big” - the first Nisei jazz musician to become a full-time member of a nationally-known jazz orchestra. Between 1943 and 1953, Paul Higaki rose to prominence as one of the first high-profile Asian American jazz artists in the 20th century.

Paul Fumio Higaki was born in San Francisco on July 28, 1924. The son of Masuichi Higaki, an Issei dentist, and Kimiko, a Nisei dance instructor from Hawaii, Higaki grew up on Buchanan Street in San Francisco. As a boy, he joined his local Boy Scout troop, Troop 12, and had his first taste of music as a bugler for the troop’s drum and bugle corps (it was in this same drum and bugle corps that Higaki met a young Harry Kitano and introduced him to jazz).

Higaki switched to trombone while in middle school at the age of 12, and after falling in love with the instrument. Even from a young age, Higaki demonstrated a natural talent for the trombone. In high school, he joined the all-Nisei Sonichi Band. By age 17, he performed at the JACL’s “Show of Shows” in May 1941, and made several appearances on San Francisco radio station KGO. In September 1941, Higaki and several other Bay Area Nisei musicians organized the Bay Region Nisei Swing Band.

In April 1942, the Higakis were sent with other incarcerated Japanese American families from the Bay Area to the Merced Assembly Center. While there, he formed a popular jazz combo titled “The Stardusters.” Later that fall, the family was then sent to the Amache concentration camp in Colorado. His father Masuichi ran the camp’s dental clinic.

At Amache, Higaki immersed himself in music; he continued to perform with The Stardusters and gave several solo performances. On Christmas Eve 1942, he performed a solo piece for trombone at the camp talent show. For the same show, his mother Kimiko gave a presentation of “odoris and colorful kimonos.” He joined the high school band, gave several solo performances, and worked as an assistant to Amache music teacher Ted Hascall. Hascall later wrote a reflection about his time work at Amache with Higaki for The School Musician magazine in March 1943.

Only a few months after he arrived at Amache, Higaki’s time in camp came to an end. In May 1943, after graduating from Amache High School, he enlisted in the U.S Army’s newly-formed 442nd Regimental Combat Team and left Amache. While training at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, Higaki helped organize the first regimental swing band. On June 19, 1943, the nearby paper, The Hattiesburg American, reported on Sergeant Jun Yamamoto’s new band and the inclusion of two mainlanders – trombonist Higaki and trumpet player George Eto – among the majority-Hawaiian Nisei band. His service in the 442nd, however, was cut short when the army discharged him on medical grounds six months later. After leaving the service, he returned to Amache to reunite with his parents.

Soon after returning from Camp Shelby, another chapter in Higaki’s life opened when, on November 24, 1943, he received a telegram from Omaha, Nebraska. Addressed to Paul Lee – the stage name Higaki created to hide his Japanese surname and avoid anti-Japanese prejudice – the telegram offered him a spot in Jimmy Barnett’s Midwest swing orchestra with a salary of “50$ weekly” – a vast increase from the pitiful 19 dollars a month he earned in camp. Higaki seized upon the opportunity to make money and leave camp, and departed for the Midwest, ultimately settling in Chicago.

Higaki’s time in Chicago proved to be important chapter for his career. From 1944 to 1946, under his pseudonym Paul Lee, Higaki joined several jazz groups and toured throughout the Midwest, starting with Lee William’s Orchestra in 1944. In William’s orchestra, Higaki toured throughout the Midwest. In 1945, he briefly played with Bob Cross’s band, and shortly thereafter joined the Allen Reed All Girl’s Band. Although newspapers remarked on the odd choice of group, Higaki stated he enjoyed performing with Reed’s band.

His trombone skills then earned him a spot in Lucky Millinder’s orchestra. Millinder’s Chicago big band included performers such as trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, saxophonists Bull Moose Jackson, Tab Smith, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, and pianist Sir Charles Thompson. While in Chicago, Higaki met his first wife, Milly Dean Walls.

In December 1946, Higaki and Walls returned to San Francisco. There, Higaki organized an all-Nisei jazz combo that peformed regularly at community events. When band leader Jimmy Lunceford heared Higaki play at a local gig, he offered Higaki a spot in his orchestra. Lunceford’s orchestra, while small, was often considered equal to other big acts of the period, such as the orchestras of Duke Ellington, Earl “Fatha” Hines, and Count Basie. Higaki’s reputation as a gifted and hardworking performer established him within jazz circles and earned him mentions in Billboard and Down Beat magazine. Higaki continued to tour throughout the U.S. from 1946 to 1949 – still under the pseudonym “Paul Lee” – even as he commuted back to San Francisco to be with his wife and children.

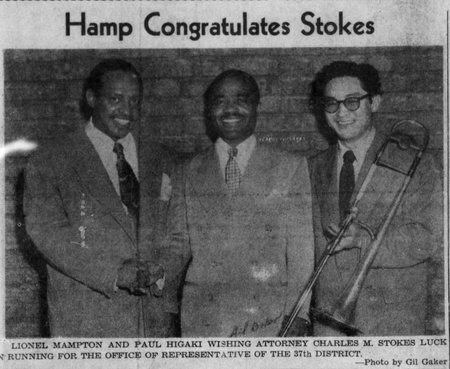

In June 1949, Higaki met Lionel Hampton during the bandleader’s visit to San Francisco. Impressed by Higaki’s abilities, Hampton hired Higaki to join his orchestra. Although Higaki was not the first Nisei to perform with Hampton – several, including Jimmie Araki and Susume Takao had performed with Hampton in Los Angeles – Higaki became the first Nisei to become a permanent member of a jazz orchestra. Higaki performed with Lionel Hampton’s orchestra from 1949 to 1952.

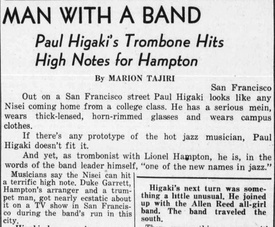

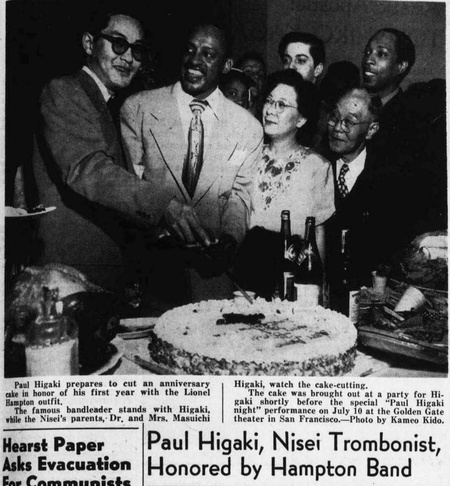

At the height of his career in 1950, Higaki was lauded as a success story, and was written up by the Japanese American press and several national news outlets as a prominent Asian American jazz cat. Hampton devoted significant attention to Higaki as a member of the orchestra. When the Hampton orchestra returned to San Francisco to perform at the Golden Gate Theater on July 10th, 1950, Hampton dedicated the program to Higaki as “one of San Francisco’s own.” The performance, which was televised live and recorded on radio, likely represents the first time a Nisei performed on television. Hampton singled out Higaki as “one of the new names in jazz today.” Higaki received congrats from several big-name celebrities, including Walter Winchell, Jackie Robinson, and Ed Sullivan.

Following up on the performance, Guyo Tajiri profiled Higaki’s new stardom for the July 22nd issue of the Pacific Citizen, noting in particular his humble origins and his cool attitude towards fame. Higaki spoke candidly about the discrimination he throughout his career. Ironically, the worst prejudice came from his being classified as “white.” When touring with Hampton in the Deep South, he was forced to find separate lodging from his fellow bandmates, and was told by white stage managers not to blow his trombone during concerts for fear of violating segregationist laws. He also spoke of how he was able to finally drop his stage name “Paul Lee” and use his real name once he had gained recognition with Hampton’s group.

During his time with the Hampton orchestra, Higaki also participated in several recording sessions with Decca Records. Higaki’s credits on Hampton recordings include (but not limited to) “Cobb’s Idea,” Vibe Boogie,” “Love Like You Made,” “I Wish I Knew,” “Ding Dong Baby,” and “These Foolish Things.” In a televised performance of “Cobbs Idea,” Higaki can be seen giving one of his signature solos in which he hits several high notes on the trombone – a feat praised by several professional musicians and that earned him the nickname “The Whistler.”

In September 1950, after a performance in Detroit, Higaki received an award from Hampton as the “Greatest Japanese jazz man in America.” The event was later reported in Billboard magazine.

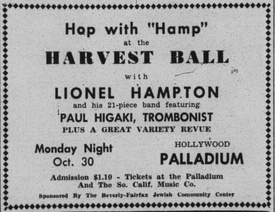

In November 1950, Higaki and the Orchestra performed at the Hollywood Palladium along with singer Karie Shindo, and later recorded a version of the jazz standard “These Foolish Things.” Hampton continued to tour with the group through March 1952, hitting major cities in the South and the East Coast.

Higaki’s time with Hampton’s Orchestra came to a sudden end sometime during the summer of 1952. According to George Yoshida in his book Reminiscing in Swingtime, Higaki and the trombonists for the orchestra were overworked after playing several gigs at the Latin Casino in Cleveland. Al Grey, one of the trombonists for the group, recalled that the whole section left mid-performance on the last night after Hampton and two others jammed for over an hour and a half overtime. When Hampton later began playing “Flying Home,” the program closer, Hampton realized his trombone section was absent. Gladys Hampton, Lionel’s wife, then fired the whole section for missing the end of the performance. While most of the section was later rehired, Higaki and several others were not. Yoshida does not provide an explanation, but he suggests that Higaki actually quit due to burnout after an exhausting few years of touring.

In the post-Hampton years, Higaki returned to playing local gigs back in San Francisco. At some point, Higaki transitioned from jazz to classical music, and auditioned several times for classical symphonies. Yoshida recounts a story by Kiyoshi Kawahata, a close friend of Higaki, that Higaki showed up to an audition for the San Francisco Symphony, but prepared the wrong piece for the audition. Devastated, Higaki failed the audition and searched for work elsewhere.

Higaki moved to Reno, Nevada to restart his life. He found work at several casinos – often working keno tables - and became a member of the Reno Symphony Orchestra and the Reno Opera Company. At the same time, he moonlighted as a musician for the casinos and was head of Reno Musicians’ Union Local 368. In 1967, he attended classes to earn teaching credentials to become a music teacher. He also became active in local politics, and campaigned for Eugene McCarthy’s presidential bid in 1968.

His life in Reno was tumultuous; at some point, his wife divorced him. He then remarried to Joan Mestayer, but the couple soon divorced within a few years. In July 1969, burglars broke into Higaki’s car and stole two of his trombones. In August 1971, the Reno Gazette-Journal listed Higaki as having filed for bankruptcy. In May 1973, Higaki remarried his third wife, Bonnie Smith, a co-worker at a casino.

On the night of December 20, 1973, tragedy struck: shortly following a performance of Handel’s Messiah at the Pioneer Auditorium in downtown Reno, Paul Higaki and Bonnie Smith Higaki were confronted by Smith’s ex-husband Edward Smith, who pulled out a hunting rifle and killed the couple on the spot. Higaki was 49 years old. The tragic murder of Higaki and Smith shocked the city of Reno, and led to a two-year jury trial. During the trial, Smith’s attorney cited his previous mental health history being a factor, whereas the prosecution used testimony from Smith’s son that Edward had created an abusive household that led his son and Bonnie to flee. On January 29, 1976, Smith was found guilty by the jury and sentenced to death.

In the years following Higaki’s murder, several fellow musicians celebrated Higaki’s legacy. UCLA professor Harry Kitano later recalled his friendship with Higaki in a piece in the Rafu Shimpo in October 1990. Like Paul, Harry played the trombone and also took the stage name “Harry Lee” during his musical career to avoid anti-Japanese discrimination: “We grew up in the bay area and played trombone in junior high school. He changed his name to Paul Lee and performed around the same area. As far as I know, we both were the only professional Asian American musicians to play in all Black bands.” Kiyoshi Kawahata, a friend of Higaki, recalled that Higaki inspired him to pursue his passion in music despite his parents’ objections: “While I was in high school, my father clearly opposed my electing music as a profession. A friend who actually did choose to become a working musicians was Paul Higaki. Paul always had inborn artistic qualities and was a nonconformist. He was a gifted trombonist and my first encounter with him as a professional was when I heard his band play a dance at the San Francisco Buddhist Church, ca. 1947.” Writer and City Lights Bookstore owner Paul Yamazaki recalled in an interview about his research on Nisei musicians that Higaki was unique: “out of that group of people not many went on to be professionals, but there was this one guy Paul Higaki, who after camp went on to work with Lionel Hampton for three years. He’s the first professional jazz musician that we’ve been able to trace.“ To honor Higaki, the University of Nevada Reno created a music scholarship in his name. In 1995, the magazine Nikkei Heritage devoted an article to Higaki’s career.

Although his tenure with Lionel Hampton’s orchestra was brief, Higaki left a considerable legacy. As one of the first Asian American jazz musicians who “made it big,” Higaki was a trailblazer who inspired several musicians to follow in his footsteps. Indeed, several Japanese American musicians, such as Paul Togawa, played with Hampton and found their own niche with the jazz world. Today, Higaki’s musical legacy lives on his recordings and television appearances with Hampton’s orchestra, several of which can be found on Youtube today.

© 2023 Jonathan van Harmelen