A number of scholars, including Nancy Matsumoto, Jasmine Alinder, and Elena Tajima Creef among others, have discussed photographer Ansel Adams’s landmark 1944 volume Born Free and Equal. The story behind the book remains fairly obscure, especially Adams’s connection with Harold Ickes.

Ansel Adams was nearly forty years old and already a famed photographer, renowned for his classic Western landscapes, when World War II broke out. Too old for military service, he took on various civilian functions.

Perhaps paradoxically, it was one of the jailers of Japanese Americans who first inspired Adams to take action on behalf of them. In 1943 Ralph Merritt, project director at Manzanar, who was a friend of Adams from their prewar participation in the Sierra Club, suggested that he come to Manzanar and document the camp site by his photographs. Manzanar was constructed in a key location in Southeastern California—within an easy drive of Death Valley, the lowest place in the Americas, and Mount Whitney, the highest—and it offered a striking field for a photographer of nature.

Adams also had powerful feelings of sympathy for Japanese Americans and outrage over their arbitrary confinement. Such a visit would thus represent a providential opportunity for him to join the professional and the personal. In fall 1943, Adams agreed to visit Manzanar. While Merritt promised him access, Adams refused all official sponsorship, whether government or institutional, and travelled at his own expense.

After his return from his visit, Adams developed the photographs he had taken and selected them for exhibition and publication. His initial plan was to release them in September 1944 by means of a show at the Museum of Modern Art and a book of photos, each to be titled Born Free and Equal. However, the planned MOMA exhibition was soon threatened with cancellation.

On the one hand, there was a real shortage of venues. The museum’s Photography Center had recently closed, as part of a full museum reorganization; while the Circulating Department's quota was already full. More broadly, due to wartime hostility to the Japanese enemy, some museum directors expressed opposition to showing any images of Japanese Americans. Under pressure from Adams and his allies, the museum finally relented and rescheduled the exhibition for fall 1944.

However, as a result of the controversy, Adams was forced to make compromises that weakened his presentation. First, his proposed title “Born Free and Equal” was changed to the more ambiguous “Manzanar.” Meanwhile, Adams was forced to excise several important parts of the text he had prepared to accompany the photos, such as the text of the Fourteenth Amendment, and the records of Japanese Americans in the armed services.

The exhibition opened at MOMA in November 1944. The museum’s official press release underlined that the photos were all of Japanese Americans of proven loyalty, and added that:

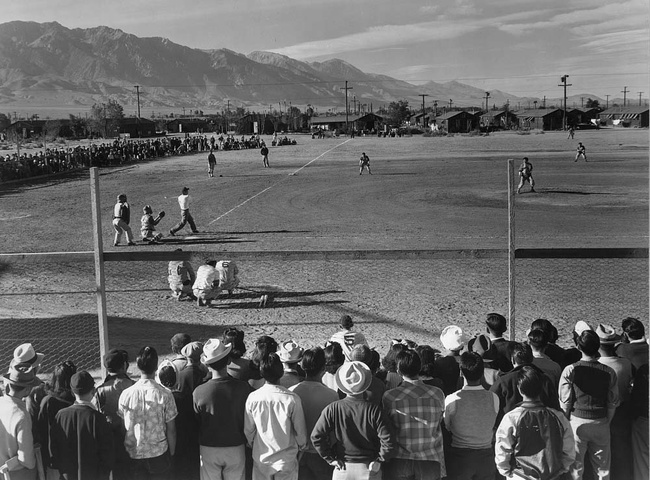

“These pictures of the flat desert expanse of the Manzanar valley between the saw-tooth wall of the Sierra Nevada along the West and the foothills of the Rockies toward the East, show a baseball field with a game in progress; young Japanese women learning to cut, fit and make clothes; children of high-school age playing volleyball; the even rows of the huge and well-tended community farm; the wide and dusty streets lined with barracks; bobby-socked girls on their way to school; interiors of homes made cheerful and livable by their temporary inhabitants; the office of the Free Press; and illuminating portraits of these loyal citizens—the faces of babies, youths, soldiers, nurses, parents and the very old.”

The book project also hit snags. Adams had offered the project to U.S. Camera, a magazine devoted to art and news photography to which he had long been a contributor. However, U.S. Camera had few resources for copy editing and layout. Adams was on the road and had to communicate by letter or telephone with the single assistant assigned to the project.

In the end, Born Free and Equal: Photographs of the Loyal Japanese Americans at Manzanar Relocation Center, was published in late 1944. The cheaply printed red paperback sold for two dollars and featured 64 of Adams's photographs.

The publication bears the mark of its hurried compilation. The text and photograph sequence is erratic, and Adams’s original text was cut down significantly. All the same, the book is a triumph. Adams's photographs, many of them close-up portraits, offer a powerful and profound representation of the humanity of Japanese Americans and their response to mass confinement.

It is worth underlining that Adams’s pamphlet was not a documentary, still less a nature photographer’s portrait of a human landscape. He did not take photos of protesting or recalcitrant inmates, or speak about “no-no boys” or draft resisters. Why? As his subtitle, “The Story of Loyal Japanese-Americans” indicates, Adams was a man with a mission.

Like Nisei author/artist Mine Okubo, who had recently illustrated the special issue of Fortune magazine on Japan that included an article on the camps, and who would publish the graphic memoir Citizen 13660 two years later, Adams’s principal goal was to to help publicize the need for re-integration of Japanese Americans into mainstream society after the war. In order to do that, he needed to show Issei and Nisei as good Americans.

In fact, the last part of the book, entitled “the problem.” focuses on Japanese Americans as representing the future of democracy in America. Adams is clear that their fight is that of all Americans, who should therefore support them:

“We as citizens can agitate for tolerance and fair play, but our agitation must be dynamic and persistent. It is easy for a fair weather lover of the constitution to favor tolerance, and mouth the principles of democracy, but it is quite another thing to stand up against opposition and fight for those principles.”

Whereas his initial trip to Manzanar had been carefully unofficial, Adams secured official support for publication of the final book. The War Relocation Authority performed fact-checking and approved the text and images. Adams secured a powerful ally, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, to write the introduction. At the time of Executive Order 9066, Ickes had privately deplored the proposed “evacuation” as an unnecessary and cruel gesture. Once president Roosevelt moved the WRA under the Department of Interior in early 1944, Ickes proved to be a resolute and forthright champion of the rights of Japanese Americans.

On April 13, 1944, Ickes made his first public statement about the WRA following the transfer. The Secretary of the Interior emphasized the rights of Japanese-American citizens and loyal aliens and asserted that they should not be confined any longer than the necessities of war demanded. He denounced anti-Japanese-American groups on the West Coast as “professional race-mongers” who hoped to resolve the situation of the Japanese Americans “on the basis of prejudice and hate,” and accused them of opposing the WRA in the past “for not engaging in this sort of lynching party.”

In the weeks that followed, during Spring 1944, Ickes and his deputy Abe Fortas worked to win the support of the War Department and Justice Department for the opening of the camps, and brought up to the president the injustice of continued confinement and the negative results for Japanese Americans in the camps, embittering those who would otherwise be “well-meaning and loyal.” However, President Roosevelt was wary of allowing return of Japanese Americans to the West Coast in a wartime climate of hostility, and amid a presidential election season. Instead, he ordered Ickes to continue the existing “resettlement” policy of scattering Japanese Americans in small groups around the country, and declined to lift exclusion.

Several months later, after the November 1944 election, Ickes again tried to press the President to take acton to lift exclusion and assist Japanese Americans in returning to the West Coast. It was at this point that Born Free and Equal came into play.

At Christmas 1944, Ickes sent Roosevelt an autographed copy of Born Free and Equal as a present, and recommended his own introduction as a guide to help the President plan policy on Japanese Americans. Roosevelt, who was nearing the end of his life and occupied with the direction of the war effort, seems not to have been interested. Instead, according to surviving memos in the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, he ordered the book placed in his library unread alongside other gifts.

In the end, according to the Library of Congress website, Born Free and Equal received positive reviews and actually made the San Francisco Chronicle's bestseller list for March and April of 1945—a remarkable achievement for a book about Japanese Americans. It was poorly distributed beyond the Bay Area, however.

Newer editions followed in later years. In 1988 a new book of Adams’s photos, titled Manzanar, was published, with text by Peter Wright and a foreword by famed journalist John Hersey. A hardcover edition of Born Free and Equal was produced in 2011 by Spotted Dog Press. It corrects surname and chronological errors found in the original and includes essays by two former inmates, photographer Archie Miyatake and activist Sue Kunitomi Embrey. In later decades, his original edition became a collector’s item. One of my proudest moments was when a dear friend, the author Sanae Kawaguchi, gifted me her copy.

Adams donated his collection of Manzanar photos to the Library of Congress in 1965. The book remains available in digitized form on the Library of Congress website.

© 2023 Greg Robinson