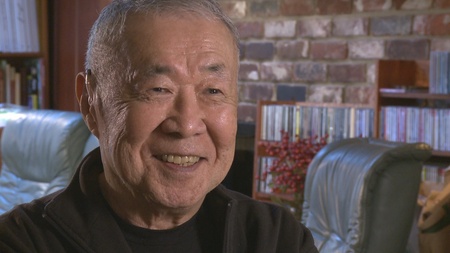

May 3, 2023 marks the 100th birthday of the late Bay Area scholar and advocate Paul Takagi. As professor at UC Berkeley, Paul helped shape the university’s School of Criminology, adopting the “crime and social justice” approach of Radical Criminology.

In Fall 1969, he taught the first course in Asian American Studies at Berkeley, helping usher in a new field of study nationwide. Meanwhile, Paul and his wife Mary Ann Takagi, together with Raymond Okamura, helped lead the fight to repeal Title II of the 1950 McCarran Internal Security Act, and provided support for Japanese American redress, as well as other civil rights causes. I have already written in these pages about Paul’s professional career. As we approach his centenary, I wish to speak about the private man I knew.

I first met Paul Takagi in June 2005. Some time before, as part of my researches on famed Nisei journalist Larry Tajiri, I had interviewed his partner Guyo Tajiri. She introduced me to her good friend Paul Okimoto, and we became a fond threesome, discussing opera and literature. They in turn kindly took me up and brought me into their circle of friends.

Paul Okimoto explained that there was a group of East Bay Nisei who met regularly for dinner at the house of the writer and performer Toru Saito and his wife Bessie, and he arranged for me to be invited when I was next in town. He told me that Paul Takagi would also be present. He added that Paul had admired By Order of the President, my book on Franklin Roosevelt and Japanese Americans, and wished to ask me questions about it.

I was flattered to hear of such interest, but uncertain what Paul Takagi might ask. While at conferences of the Association for Asian American Studies (AAAS) I had seen Paul’s daughter Dana Y. Takagi, an eminent sociologist and one-time president of AAAS, but I knew much less about her father’s work. What is more, my new friends told me that Paul could be bad-tempered and curmudgeonly, and that he had suffered serious hearing loss, which made for further troubles dealing with him.

The dinner turned out a very pleasant occasion. It was great fun to have a home-cooked Asian meal and meet a whole group of boisterous and colorful Nisei elders. At one point, I mentioned that I had performed in a high school production of Guys and Dolls. One of my hosts asked about a song from the show, “More I Cannot Wish You,” as they had trouble recalling the lyrics. They were delighted when I sang the song for them—my knowledge of musical theater stood me in good stead!

After the main meal was over, the dishes were cleared from the big table. Paul Takagi invited me to sit across the table from him and talk about my book. He put a microphone in front of me, and attached it to a pair of hearing aids in his ears. While it did give me a slight feeling of testifying before a legislative committee, at least that way he could hear without my having to shout. I explained what I had written in my book and answered his questions.

In response, Paul told stories about his life. Most notably, he recounted a poignant narrative of how, while confined at Manzanar as a teenager, he had worked as a medical orderly at the camp hospital. He was there in December 1942 when Jim Kanagawa, who had been shot by Military Police during the so-called “Manzanar riot,” was brought in. Takagi remained in the hospital all night, watching over Kanagawa as the young man’s life ebbed away.

When the dinner was over, I gave Paul Takagi a warm goodbye and told him I hoped to see him next time. Paul Okimoto told me afterwards that he was surprised at how open and warmhearted the curmudgeonly Paul Takagi had been during my visit. Apparently recounting his tale about Manzanar, which he had never shared with his friends, had led Takagi to feel depressed in the next days.

I wrote to Paul Takagi by email shortly afterwards to send some promised information. He wrote a long and fascinating response, which led to an extended correspondence. Our letters naturally dealt a lot with Japanese American history. I sent him some drafts of my new writings and read his drafts, or recommended books that I thought might interest him. Paul was absorbed by the connection between Eugenicist thinking and anti-Japanese official actions. I thought there was a case for it. I shared with him what I had found on the subject and gave my impressions.

In addition to our correspondence, I began the habit of meeting up with Paul Takagi when I would come to the Bay Area. It was easier for him to hear when we were alone together in a quiet place, and probably easier for him to face. While Paul always seemed pleased to see me, I knew from him and other friends that he struggled with poor health as well as with depression.

It was early in our friendship that Paul invited me to come visit his house in the upscale—and uphill—Bay Area community of Piedmont. Paul told me he had moved into the house in 1964. Surprised that a non-white family had been able to move into such a community at a time when racial discrimination in housing was both widespread and legal, I responded facetiously, “Yes, I’m sure the locals all came out to welcome you. Do you still have the spot on your lawn where they burned the cross?”

It was a nervy joke, but it cracked Paul up.

One aspect of our relations I treasured was Paul’s generosity in encouraging me. He expressed to me the hope that I could be recruited for a position in Asian American Studies at a West Coast university, and I know that he talked me up to other people. I was not only honored that he held my work in such high regard, but as a non-Asian in an Asian field, I thought that it was really high-minded of him to promote me.

I remember once Paul invited me over when he was receiving a visit from the eminent UC Berkeley sociologist Michael Omi, an old poker-playing buddy of his. Beyond the intellectual content, Paul may have hoped that Omi would use his professional influence on my behalf. I did not expect anything concrete to come of it, though it was quite a pleasant visit nonetheless.

Through his writing and our conversations, I learned a lot about life in general, and Paul’s life in particular. He defied so many easy stereotypes. For example, he told me, “I grew up on a farm so I’ve always had a fascination for hand guns—I have several—and power tools, weed cutters, and chain saws. Along with a fascination for power tools I drive a 4-wheel-drive pickup truck. Yup, I do wear cowboy boots.”

He also had a background as a manual laborer. Paul told me that after being released from Manzanar in 1943, he moved to Cleveland, where he worked as a “swamper” loading and unloading trucks, and joined an AFL union. “I was happy working out doors and meeting people I've only read about - Jews, Pollocks (not my word, theirs), Greeks, and people from the Ukraine - all of us getting the same pay,” he later recalled.

I was fascinated by Paul’s admiring references to his younger sister Hannah Tomiko (Takagi) Holmes, a deaf woman who became a prominent activist both on behalf of Japanese Americans and the handicapped. Indeed, Paul’s regard for his sister helped him to form a bond with S.I. Hayakawa, the future conservative college president and U.S. Senator, until they were separated by politics. Not only were Takagi and Hayakawa among the few Asian American academics at mainstream universities outside the sciences, and each had a passion for African American music, but they shared the experience of caring for handicapped family members. (Hayakawa’s son Mark was a Down’s Syndrome baby).

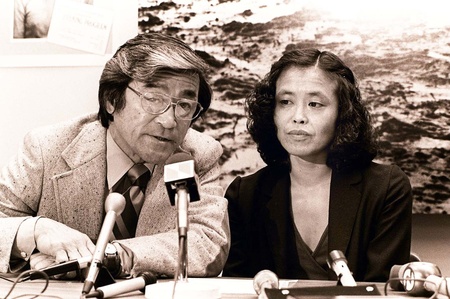

Regarding caring for people, I was amazed by Paul’s stories of helping Wendy Yoshimura when the young Sansei radical was arrested for being a member of the Symbionese Liberation Army. Paul saw the human being behind the politics—he expressed compassion for her as coming from a family that had been hard-hit and impoverishedd by mass removal. Paul guaranteed her good conduct after her arrest so that she could be released from prison on bail, and Wendy stayed at his house during her trial.

In addition to seeing Paul alone, I attended some more of the Nisei group dinners. (I recall that Toru Saito generously invited me to sing for the group at one such dinner, and I gamely did my best). Paul took the lead in cooking at those parties. He was famous for his chow fun. Once when I came in late fall, Paul served sukiyaki. I had only recently tasted sukiyaki for the first time, and Paul’s home-made version was quite memorable.

It may have been at that dinner that I had the pleasure of announcing confidentially to the group that Paul had been selected for a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Association for Asian American Studies. Because I was on the AAAS Executive Board, Paul and the other group members assumed that I had been chiefly responsible for the award. I countered that the AAAS leadership had in fact relied heavily on the advice of an esteemed scholar and former AAAS president. “What former president?” I was asked. “Dana Takagi!” I deadpanned, making the entire table break up with laughter.

Paul was deeply touched by the award, and despite my disclaiming of credit, he expressed fulsome gratitude to me. In Spring 2008, he made a trip to Chicago to accept the award at the AAAS annual meeting, and he invited me to join him and his family as a special guest for lunch and a tour of the city. It was an extraordinary experience to walk with Paul around Millenium Park. He told me of settling in Chicago in 1945, after being discharged from the legendary 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Paul told me that sometimes he had no money and would spend the night on a park bench. He also told me of the African American jazz clubs he frequented on the South Side.

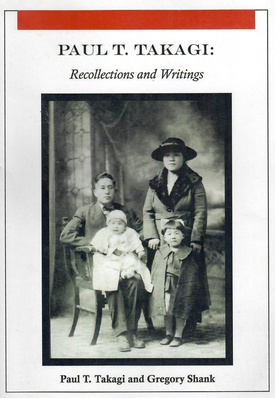

I had less contact with Paul after 2010. He was working with his collaborator Gregory Shank on the project that saw print in 2012 as Paul T. Takagi: Recollections and Writings. Meanwhile, as he neared his 90th birthday, Paul’s physical condition declined, and some reverses in his personal life left him deeply depressed.

At one point, I wrote Paul to say hello. I received a warm message from Paul. He thanked me for my friendship, but stated that he had been diagnosed with dementia and was going to have to withdraw from corresponding. Paul’s daughter Dana told me later that her father was secretive about his dementia, so the fact that he confided in me was a real mark of his trust and affection.

Paul died in 2015. I will always be glad that I had the chance to get to know him. Not only was he was an engaging and generous friend, but his brave struggles served as an inspiring human lesson in perseverance.

*If you want to know more about Paul Takagi, please read this other essay by Greg Robinson here.

© 2023 Greg Robinson