In my 73rd year, I began to gather memories of 1973 and the moments leading up to that time. Fifty years have passed since the end of the war in Vietnam. I graduated from high school in 1968, a year behind most of my classmates, at age 19. Moving to California from Wyoming must have had something to do with me being older than everyone else in the class.

I was one of two Asians in the school, and I caused trouble by wearing a Navy watch cap. The principal threatened to expel me just before graduation and I learned that I had to be subservient to people in power to get what I wanted. The principal thought I should go to a military academy for college. Guess he thought the discipline would be beneficial. I wanted to get out of that school.

In the fall of 1968, I started college at the only campus to which I had applied. Once again, I was one of three Asians at the school at that time. I found that many students had transferred to Humboldt State because of the San Francisco State shutdown and the demonstrations there. San Francisco State students finally went on strike for ethnic studies and the San Francisco State campus was closed from November 1968 to March 1969.

There were too many students at Humboldt State that fall. The residence halls were filled, I was unable to find dorm space, and housing was scarce. Registration was shut down so more classes could be added to accommodate the number of students who increased enrollment.

I had not been very conscious of the war in Vietnam despite all the media coverage at the time. I remember a high school classmate telling me that he was interested in joining the Air Force, and I asked him if he would be comfortable bombing people indiscriminately. I was at least aware that the war had many, many casualties. My first fall semester in college, I heard of the demonstration by students at Humboldt regarding the war. A march through the town of Arcata by students was organized.

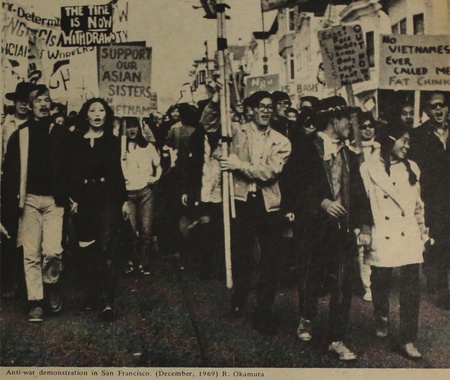

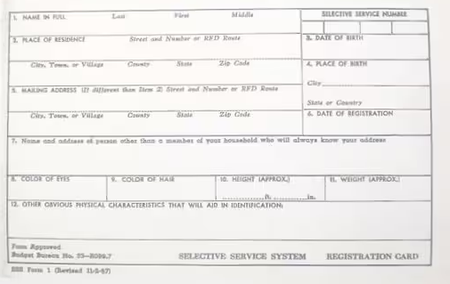

The next academic year, in December 1969, the draft lottery was implemented by the Selective Service. Based on birthdays, numbers were randomly assigned and males were drafted based on their lottery number. The system was put in place due to the many mass protests against the Vietnam War and universal conscription that was in place at the time.

Guys in the residence halls hung their lottery number out the windows of their rooms. Individuals were called and drafted into military service annually depending on the need of the military, starting with number 1 and going through 365 until the required number of draftees for that year was filled. The higher the number, the less likely to be drafted. My number was 94, a low number.

In the summer of 1970, I visited northeastern Oregon and the family of a friend I met at Humboldt State. I drove there with a couple friends. They continued on to the East Coast. I decided to hitchhike back to Los Angeles, and made it to San Francisco, where I decided to catch a flight to LA.

At the San Francisco airport, I encountered thousands of guys in uniform on their way to Vietnam. It was astounding. They were all my age, and I was one of the few civilians. I was feeling guilty. I saw an Asian guy walking through the airport in fatigues, and all the guys in uniform stared at him as he walked by.

After two years, I decided to transfer out of Humboldt for UCLA and went there in the fall of 1970 hoping to meet more Asians. I knew one Asian guy there. In March 1969, President Nixon began a bombing campaign in Cambodia, neighboring Vietnam, as part of the war. The bombing continued until May 1970.

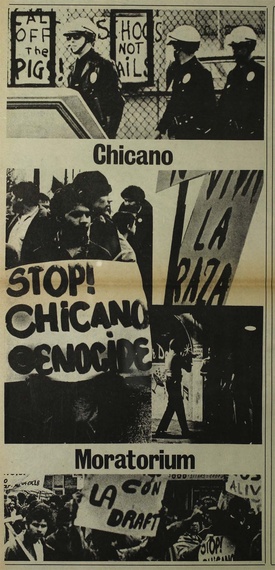

On August 29, 1970, Chicano students, including UCLA Student Body President Rosalio Muñoz, organized the Chicano Moratorium in East Los Angeles to protest the Vietnam War. Some 20,000–30,000 people marched and peacefully demonstrated in East LA against the war. Los Angeles County sheriffs responded and three people were killed, including Los Angeles Times journalist Ruben Salazar.

In 1972, police swept the UCLA campus due to the anti-war demonstrations that had taken place. A student there who I knew was just walking to class and was caught in the chaos of the sweep.

I was asked afterwards to pass out flyers about a teach-in and alternative classes being held to discuss the war. Some students took the flyers and thanked me, and other students refused and said “f**k you.” This surprised me, as I was only trying to pass on information. I went to Japanese class after passing out a few flyers, and a woman in the class just started shaking her head “no” as I began to explain what I was doing. People didn’t even want to hear about the war.

My four-year student deferment from the draft was to expire in 1973. My classification was Class IIS, for deferment due to activity in study. Because I transferred, had failing grades, and had administrative mistakes on my college record, I would not be able to graduate before the deferment ended.

My options were to leave the country for Canada as many had done, go underground and attempt to disappear, or actively become a draft resister. I could not claim to be a conscientious objector, as I had no history or religious affiliation to demonstrate that claim.

I had to register at the draft board office in Hollywood, California, and the next step would be induction to the military. The war was still ongoing. I was scared and did not want to end up in Vietnam in what seemed to be more and more a senseless war. I was certain I would be killed if I was drafted.

In the days before the Internet and such resources, I went to see draft counselors on campus. They were not helpful at all, so I went to the UCLA Law Library to read the draft law for myself. I discovered that if I was not called for the draft by December 31st of 1973 and my classification was 1-A instead of deferred, I would be placed in second priority. Class 1-A meant available for military service. Second priority meant that lottery numbers 1–365 would be called before the second-priority individuals.

I knew that the draft had been suspended in Los Angeles due to a suit by the ACLU regarding the draft. This injunction meant that no draftees would be taken from Los Angeles until the lawsuit was settled. I knew the lawsuit would take weeks or months to be settled. I took a chance and decided to change my status from Class IIS deferred to 1-A available, hoping that I would not be called before December 31st.

I wrote a letter to the draft board to request this change in status, and mailed it just before Thanksgiving, so it would be stuck in the mail over the holiday before being sent to the draft board. I hoped the holidays would further delay the processing of my status change, and that I would be declared 1-A, not drafted by December 31st of that year, and be placed in second priority.

I didn’t hear from the draft board until the following June, when I received a new draft card showing I was in second priority. I never had to serve in the military. In later years, I felt guilt over the many thousands of people who served, and especially those who were drafted and never made it back home.

Men who moved to Canada to avoid the draft were not given amnesty until many years later on January 21, 1977, by President Carter. An estimated 20,000 to 30,000 American men moved to Canada to avoid the draft.

In the late 1970s, I spoke to a student from Vietnam, one of a few at The University of California, Santa Barbara where I worked at the time, asking about the war. She said that all Vietnamese wanted was peace. Her statement struck me and stuck with me. I wrote a letter to the UCSB campus newspaper questioning how non-Asians adopting Vietnamese orphans would rear those children.

In those days, I also developed a lasting friendship with a Vietnam veteran, another student who served in the Marines. He was demoralized by the hostility he felt after returning to the US after his service during the war. He made me realize how much the men and women who served in the Vietnam War gave of themselves.

Many more years later in 2001, I listened to Japanese American men who were imprisoned at Heart Mountain, Wyoming. They remembered their time there and their protests against incarceration like it happened yesterday. They were still angry after 60 years.

For those who served in Vietnam, I honor their service; for those like me who didn’t serve, I honor their protests against a terrible war.

© 2023 Thomas M. Nishi