Market report broadcast begins

In the 1930s, Japanese farmers were the second largest group in California after whites, and Japanese farmers were responsible for producing vegetables and fruits for suburban markets in particular. According to statistics from 1930, 53% of employed Japanese were engaged in agriculture. The large amount of labor required for crop harvesting was met by advertising in Japanese newspapers and by hiring Mexican and Filipino workers.

In response to a strike by farm workers in 1933, representatives of 36 unions in Southern California came together to form the Southern California Central Agricultural Association in 1933 as an organization to bring them together. The Central Agricultural Association was responsible for adjusting production and shipments, entering into labor agreements with farm workers, and negotiating with other organizations.

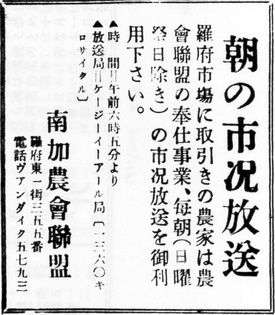

The Japanese program "Southern California Central Agricultural Association Market Report" sponsored by the Southern California Central Agricultural Association began on February 4, 1935 on KRKD in Los Angeles. It was broadcast for 15 minutes every morning.

Shinichi Kato, secretary of the Southern California Central Agricultural Association, was in charge of broadcasting, and Rihei Numata, a fellow reporter at the California Mainichi Newspaper, joined him in April 1936. As it was initially a one-month test broadcast, it had to be broadcast before 6:00 a.m. with low transmission output, making it an early morning program.

According to the California Mainichi Shimbun (January 29, 1935), the program content was as follows:

- Breaking news on market arrivals, market conditions, prices, and remaining stock on the morning of the day

- weather forecast

- Previous day's Eastern market conditions

- Broadcasting of reference materials (warnings on crackdowns on fraudulent packs, news on the US agricultural industry such as crop yields and cultivated areas in various regions that are relevant to Japanese farmers, etc.)

- News broadcast (World Major Events Compendium)

On the first day, the broadcast included a greeting from Katsuma Mukaida, president of the Central Japanese Association, and a market report from Shinichi Kato, executive director of the Southern California Central Agricultural Association. The broadcast was said to have been well received in many areas, including the Imperial Plains region.

The program got off to a good start and was well received by listeners, but because it was broadcast every day, they had difficulty coming up with the money to pay the radio station for the broadcast. One month after the program began, on March 2nd, the Central Agricultural Association's board of directors met to discuss the cost of broadcasting the market information, and it was resolved that the member organizations should cover the costs, that volunteers should make donations, and that donations should be requested from non-member organizations as well.

At the board meeting on March 19, it was decided that the dues should be paid promptly and that the request for donations should be made as soon as possible. When making the request for donations, it was decided that the agricultural association directors should take the initiative in making special donations, and about 250 dollars was immediately collected, including volunteers from Chairman Harutaro Takada and others.

Under these circumstances, the broadcast time was extended to 30 minutes from 5:30 a.m. on March 18. This freed up time, and in addition to market conditions, lectures related to agriculture, such as "About the Anti-Japanese Land Bill" and "Container Issues," began to be broadcast.

In June 1935, the Southern California Federation of Agricultural Associations was formed with the dissolution of the Southern California Central Agricultural Association, and the operation of the market report broadcasting was taken over by the Federation. However, from the summer of that year, the number of sponsors began to decrease, leading to a lack of operating funds, and the difficult decision was made to shorten the broadcast time to 15 minutes in mid-September. In order to further reduce costs, the station was changed in early October.

Change station

The Southern California Agricultural Association restarted its market report broadcast on KGER in Long Beach on October 7, 1935. Initially, the broadcast was planned to continue as a 15-minute program until a method for raising funds for the program was established, but due to dissatisfaction that 15 minutes was not enough to report market conditions, the program reverted to a 30-minute program on October 14.

However, the financial problem was not solved, and until the Agricultural Association Federation could come up with a method to cover the expenses, they decided to cover it through special donations from volunteers. Monthly expenses were estimated at $200 for a 15-minute broadcast and $300 for a 30-minute broadcast (California Mainichi Shimbun, October 10, 1935).

Fortunately, donations from local farmers kept pouring in, but there was a limit to how much they could support the station. Despite this financially unstable situation, Kato's efforts allowed the station to continue broadcasting.

On February 22, 1936, the Southern California Agricultural Association held a regular meeting of representatives and passed a resolution to "establish a radio broadcasting department." Starting March 16, the start time of broadcasting was changed to 5:30 a.m. The official reason given was that it was spring, when the sun rose earlier and farmers needed to get to their fields earlier, but in reality it may have been the result of choosing a time slot with cheaper broadcasting fees.

Feud with the California Mainichi Shimbun

When the program first began, the California Mainichi Shimbun sent words of encouragement to its former colleague, such as, "Finally, Kato's Arata-chan has become the announcer and is making an appearance, saying, 'Good morning everyone...'" (California Mainichi Shimbun, February 1, 1935). However, from around August 1936 the deterioration of the relationship between Nokai Renmei Broadcasting and the California Mainichi Shimbun became apparent, and the paper began to frequently publish criticism of Nokai Renmei Broadcasting (or Kato and Numata personally).

The background to this is the conflict over the policy issue when the issue of agricultural labor strikes came to light in 1936. The Agricultural Association Federation (Executive Director Kato) instructed its members to stick to their stance of refusing to recognize the labor union. On the other hand, there were local organizations that wanted to recognize the union and resolve the issue quickly, and the California Mainichi Shimbun supported them, arguing that instead of taking a uniform approach, the issue should be resolved according to the circumstances of each region.

At first, criticism of the California Mainichi Shimbun was limited to the fact that the broadcasting income and expenditures were unclear and that they should clarify how donations were used. However, in October, the Gardena Plains Agricultural Association protested against the Agricultural Association Federation's policies and withdrew from the federation, which led to an explosion of criticism of the California Mainichi Shimbun in its market report broadcasts. Here is one example from the California Mainichi Shimbun newspaper:

The news has been reporting that the manager of the Agricultural Union, Kato Shinichi, has been slandering and defaming the California Mainichi Newspaper and President Fujii for days on end, [omitted] and furthermore, our station extended its broadcast time to lash out at President Fujii with harsh and nasty language that is unbearable to listen to, and in connection with this, it also made shockingly abusive remarks against the farmers of Cardena Plain.

Manager Kato not only declared our article to be a "big lie," but also re-read the script he had written attacking President Fujii the day before and boasted that our article was a fake. However, what surprised me even more was that the script was serialised with even more slanderous words against President Fujii than the article in our newspaper.

For example, they casually broadcast statements such as "They are pawns of the communist newspapers" and "If you keep quiet, we will forgive you when the time comes." (...)

(California Mainichi Shimbun, October 20, 1936)

According to the broadcast by Manager Kato, he (Kato) represents the 3,000 farmers and is going to destroy the enemy of his fellow farmers, Fujii Sei, who is a worm in the lion's body, and the Gardena Plains farmers who are riding on his coattails and becoming pawns of the communists. He said that what he was saying was not just Kato Shinichi's alone, but was speaking on behalf of the entire Farmers' Union.

(California Mainichi Shimbun, October 21, 1936)

The so-called California Mainichi supporters who agreed with the claims of the California Mainichi Newspaper were not silent either. The San Gabriel Plains Industrial Association held an extraordinary general meeting in December 1936 and resolved three points: 1) to request the retirement of the Agricultural Association executives and General Manager Shinichi Kato, 2) to sever ties between the Agricultural Association and the California Agricultural Weekly, which Kato was in charge of editing, and 3) to improve the Agricultural Association broadcasting department.

Sunday night broadcast

On October 25, 1936, the Agricultural Association Federation began broadcasting on KGER every Sunday night at 8:30 p.m. The purpose of this broadcast was to convey the Agricultural Association Federation's position on the strike issue.

Representatives from around the country and Shinichi Kato appeared on the program and gave passionate speeches. On the November 8th broadcast, it was reported that "some enthusiasts counted that Manager Kato had aired the same thing about the union issue 78 times. Even the most patient person would get fed up with hearing the same thing 78 times" (California Mainichi Shimbun, November 10th, 1936).

Apparently aware that people would get bored with just his passionate speeches, he also broadcast popular songs and stand-up comedy. This nightly broadcast continued for about a month.

Terminal Topics

"Japan Telegraph News," sponsored by the Southern California Industrial Daily News, began in January 1937. Especially after the Sino-Japanese War, it was highly valued by listeners as the first source of Japanese information in the morning, as it broadcast breaking news.

In 1940, the station began reporting the results of Japanese sumo matches, much to the delight of sumo fans. In September, the station's broadcasting director, Rihei Numata, returned to Japan. His successor was Kunio Ono, a staff member of the Agricultural Association Federation who had traveled to the United States in 1936 after graduating from Aoyama Gakuin University.

The episode broadcast on Saturday, December 6, 1941 is believed to have been the final episode.

By the way, Shinichi Kato wrote "A Hundred Years of the Japanese American Life: A Record of the Development of Japanese American Life" in 1961. In it, he gives a brief history of Japanese language broadcasting in the section "Radio Japanese Language Broadcasting."

California Mainichi Broadcasting, which was run by the California Mainichi Shimbun, was broadcast for five years before the war, and although it is a program that should be mentioned, there is no mention of it. I think this shows Kato's feelings about the California Mainichi Shimbun.

References:

Yuko Matsumoto, "The 1936 Los Angeles Celery Strike and the Nikkei Farming Community" (from Shirin, 1992)

*This article is an excerpt from Japan Hour (2020).

© 2020 Tetsuya Hirahara