I had the honour of interviewing History Professor Masumi Izumi earlier this year.

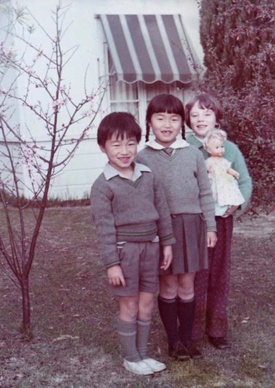

Dr. Izumi is Japanese. Her scientist doctor father’s work took the family to Australia, where she attended elementary school. Years later, she returned to Kyoto and attended public school.

She received her B.A. in Anglo-American Studies from Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, and went on to attend Queens University in Kingston, Ontario, for her Master’s studies in Political Science and International Studies. She also studied at the University of Victoria, BC, for two years under Professor Patricia E. Roy. She completed her PhD at the Graduate School of American Studies at Doshisha University in Kyoto, specializing in Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians. She is Professor of North American Studies in the Faculty of Global and Regional Studies at Doshisha University in Kyoto.

Dr. Izumi knows our Japanese Canadian story well. Throughout this interview, she opened up about factors that influenced her to become a scholar of Japanese Canadian and Japanese American history and what her own family went through during World War II.

Whenever I am in the elementary school classroom, I chuckle when my students insist that I am as “Japanese” as sushi, ramen, and anime like Naruto, Demon Slayer, and Pokemon. I enjoy feeling a momentary liberation of sorts when my Punjabi, Hindu, Gujarati, Black (African and Caribbean), Muslim, and east Asian students identify me this way.

However, I’ve lived in Japan for nine years and know that I am not “Japanese” per se, but that is the awkward label that I grew up with. Does “Canadian Nikkei” better fit the bill? It might for some, but, personally, not really. “Japanese Canadian” perhaps best describes who and what I am, but not entirely.

After the March Break, I usually pick up my copy of Righting Canada's Wrongs: Japanese Canadian Internment in the Second World War by Pamela Hickman and Masako Fukawa. I utilize its wonderful references to the early Punjabi and Black histories in BC, to begin the deconstruction process for my students. With education, it is my hope that they’ll begin the life-long process to better understand who we all are as Canadians.

Over recent years, I have had the privilege to get to know Professor Izumi in a roundabout way. My Canadian expat friend Stan Kirk in Kobe introduced me to her. They are both involved in the Mio-mura project in Wakayama-ken and its connection to the fishing village of Steveston, BC.

* * * * *

Upon following up with Izumi, I learned that she is currently at the University of Victoria, BC (UVic) as a member of the Past Wrongs, Future Choices (PWFC), an international collaborative research project on the ethnic Japanese experiences in several different countries and regions during World War II. She was selected to be a Scholar in Residence at the University of Victoria for this project, to exchange ideas and co-write research papers with UVic scholars and other Scholars in Residence. PWFC also sponsors Artists in Residence, and has met artists and scholars interested in the history of Japanese overseas, exchanging new ideas about how to develop this field of study.

Explaining her interest in Japanese Canadian history, Dr. Izumi explains:

“The direct factor that drew me to the study of Japanese Canadians was the severe ‘reverse culture shock’ that I suffered from, when I returned to Japan after studying two years in Canada and working for a year as a Japanese language instructor in the United States. I did my Master’s Degree in Political Studies at Queen’s University at Kingston, and I worked as a Japanese language instructor at Dartmouth College. Then I decided to return to Japan, but I was not happy. I moved away from Tokyo where my family lived, moved back to Kyoto where I grew up, and started living with my grandmother.

“I worked in a publishing company as a contract editor. I gradually adjusted back to my native culture, but I decided to analyze the cause of my discomfort.

“I first studied ‘Japanology,’ which was popular at the time in the early 1990s; but instead of learning what the essence of Japanese culture was, I started thinking about why ‘Japanology’ became so popular in the 1990s. I ended up writing an essay about the development of Japanology and the social and psychological factors for the popularity of the discipline. I won an essay contest for this piece. After that I started searching for what I should study next.”

She continues: “It just happened that the Japanese Association for Migration Studies held its first conference in Kyoto in 1991, and I attended it. Through this organization, I got to know scholars who studied Japanese Canadian history. I did not have any academic affiliation at that time, but I started studying under the guidance of Professor Toshiji Sasaki, who was a pioneer Japanese historian of Japanese Canadians.

“As I studied more deeply about Japanese Canadians, I got more interested, because the history touched upon many social and cultural issues—such as racism, human migration, cultural adjustments, forced relocation, human rights violations, multiculturalism, and the general issues related to social justice and social change.”

Speaking about her own family’s World War II experience, she explains:

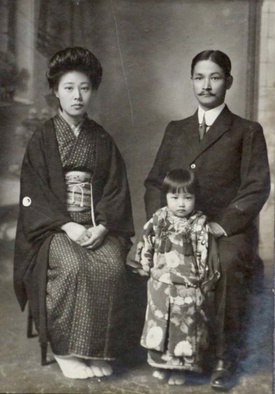

“My father was born in Manchuria. My grandparents’ family was from Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture. My grandfather worked for the Southern Manchurian Railway. My father was born in Changchun City in 1937, but I think they moved to Harbin during the Pacific War.

“On August 8, 1945, the Soviet Army occupied the town my father’s family lived in, and the Russian soldiers came into his house. My father told me that his mother had hidden all the jewelry and valuables inside a fusuma (paper door), so the Russian soldiers searched for valuables and left the house empty handed.

“My father’s family was poor, but his relatives were quite wealthy and they owned an antique store in Dalien. After the war they lost everything they had owned; but I have not heard any story about my father’s family or relatives being injured, killed, or raped, so that was very fortunate.”

Her father’s family stayed in China through the Revolution, as her grandfather was asked to train the Chinese in operating steam locomotives and help them expand the railway network. Her grandmother was a nurse. Her father’s family returned to Matsuyama in 1952.

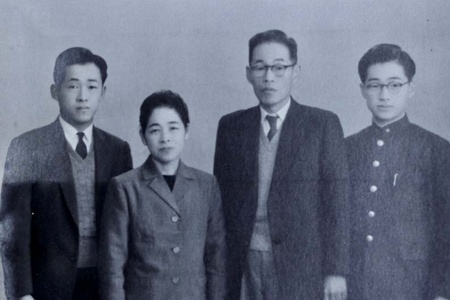

“My mother was born in Tokyo in 1937. Her father died of tuberculosis during the Pacific War. The area she lived in was not burned down by the Tokyo Air Raid on March 9, 1945, but the Harajuku area, where they lived, was flattened by an air raid on May 4. A week before this happened, my mother’s family was ordered by the Army to evacuate from Tokyo. My grandmother and her mother had to pack whatever they could carry, and took my mother and her three brothers, all still little kids, to a relatives’ place in Sanda, Hyogo Prefecture.

“My grandmother’s ancestors were originally from Kyushu, but she was born in Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture, where her father had worked on various businesses. My grandmother’s father could speak English, because his father worked for an English insurance company in Kobe. So my mother’s family lost all the property they owned in Tokyo during World War II, but the family survived the war.

“Shortly after the war ended, they moved to Kyoto. My mother told me that her grandmother saw the sky turn strangely dark in the western direction on August 6. She was in Kobe, so I think that was the atomic bomb.

“So I have in my family lines colonizers and complicit citizens of an aggressor state, revolutionaries in the early People’s Republic of China, survivors in war-torn nations who went through forced evacuation, dispossession, and repatriation, but all on the other side of the Pacific,” she says.

“One thing I don’t have in my family history is someone who served in the military and fought in World War II, because all the adult male members on my mother’s side of the family succumbed to tuberculosis before or during the war. One war story that is passed down in my family is that, when my maternal great-grandfather was conscripted and taken to Northern China during the Russo-Japanese War, he somehow negotiated with the Russian soldiers who could speak English and tricked them into surrendering.

“He bluffed that the Russian platoon was all surrounded and had no chance of survival, so they surrendered and the platoon my great-grandfather belonged to survived. I have the original copy of the letter of appreciation addressed to my great-grandfather from his fellow soldiers for saving their lives with his wit and language skill.

“Looking back, I realize that my lineage has a lot of transcultural experiences in it, which is continuing today.”

*All Photos Courtesy of Masumi Izumi

© 2023 Norm Masaji Ibuki