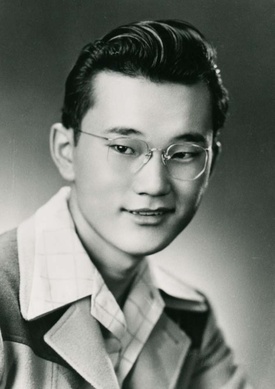

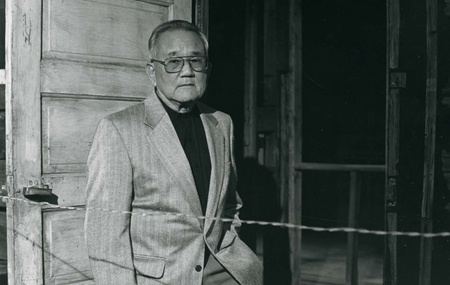

Yoshito Kuromiya was one of 63 Nisei who resisted being drafted during World War II from the Heart Mountain, Wyoming, incarceration camp for Japanese Americans (JAs). All were convicted of violating the Selective Service Act and imprisoned. Altogether, approximately 300 Nisei from eight of the 10 camps resisted the draft. Most served time in prison for it.

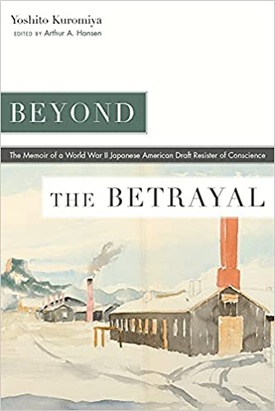

Kuromiya later went to college and became a landscape architect in Southern California. His memoir, Beyond the Betrayal, is the only one by a Nisei draft resister. It was initially submitted to an unnamed university press, which declined publishing it. Kuromiya then decided to self-publish, but only for his family and selected friends.

Fortunately, Kuromiya’s four adult daughters turned the text into a book before their father’s death in 2018. Arthur A. Hansen, a professor at California State University-Fullerton, was asked to write an introduction. Hansen volunteered to edit the book so that it could be published by University of Colorado Press. The handsome volume contains Kuromiya’s excellent watercolors and drawings and Hansen’s introduction and photographs.

Also provided are a preface by law professor Eric L. Muller, a poem dedicated to Kuromiya by Lawson Fusao Inada, a 1946 editorial from the Wyoming Eagle about the then upcoming trial of the Nisei draft resisters, an excerpt from a 1988 Pacific Citizen newspaper column quoting noted Nisei writer Bill Hosokawa, and an essay by Kuromiya from A Matter of Conscience: Essays on the WWII Heart Mountain Resistance Movement, a book published in 2002.

Kuromiya was not a “no-no boy.” He answered question 27 of the government’s loyalty questionnaire—was he willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty wherever ordered?—“yes,” on the condition that he be accorded the same rights as a Caucasian citizen.

As to question 28—would he swear unqualified allegiance to the US and faithfully defend it from any or all attacks by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?—Kuromiya also replied with an unconditional “yes.” This was even though he’d never had any allegiance to the Emperor of Japan.

But, while incarcerated at Heart Mountain, Kuromiya had joined its Fair Play Committee (FPC), founded to protest the drafting of Nisei men into the Army. Although Nisei reasons for resisting the draft were many, he felt that so long as the mainland US was not being invaded, he could not go to a foreign country to kill others to prove his loyalty to a government that had imprisoned him and his family without due process. He felt so strongly about this that he was willing to go to jail. So when his draft notice arrived, he refused to report for the required pre-induction physical examination.

After being arrested and while awaiting trial, Kuromiya was visited by Joe Grant Masaoka and Minoru Yasui. They tried to dissuade him from continuing his opposition to the draft, arguing that “draft dodgers” were “tarnishing the extremely precarious image of Japanese Americans and were doing our people a great disservice.”

Since Masaoka was a Japanese American Citizens League official and the JACL favored accommodating the federal government, Masaoka’s position was not surprising. However, Yasui’s stance was. Yasui had challenged the military curfew that had been imposed on West Coast JAs before their incarceration. His case went all the way to the US Supreme Court, which ruled against him in June 1943. Yasui’s presence at the meeting understandably was confusing to Kuromiya.

Kuromiya was convicted and spent most of his jail time at the federal prison on McNeil Island, Washington, working on its farm. One of his biggest disappointments was his belief that his case was never appealed to the US Supreme Court. Kuromiya believed that this was because FPC leaders’ priorities had changed once they had been indicted for conspiracy to violate, and for counseling others to violate, the Selective Service Act. Although their convictions were later overturned on appeal, neither the FPC nor Kuromiya’s lawyer ever consulted with him or other Nisei at McNeil about whether additional appeals of their convictions should be undertaken.

Kuromiya later wrote, “I inquired on several occasions what the meaning was of the oft-repeated FPC motto: ‘One for all, and all for one.’ I never received an explanation.”

In fact, the case of one of the Heart Mountain draft resisters had been appealed to the US Court of Appeals, which affirmed the conviction. The US Supreme Court refused to review the case further (Fujii v. United States, 148 F.2d 298, 10th Circuit, cert. certiorari — discretionary review — denied, 65 U.S. 1406, 1945).

As is often done with multiple similar cases, the lawyers and the court had agreed that the outcome of the Fujii case would govern the other cases including Kuromiya’s. Thus, the unfortunate result of the Fujii case was applied to Kuromiya’s case, even though he apparently was not advised of it.

In any event, because of “time off for good behavior,” Kuromiya and the other 62 draft resisters at McNeil Island were released two years later, in July 1946, one year short of their three-year sentences. President Truman pardoned all of them in late 1947. Surprisingly, no one told Kuromiya about the pardon until nearly three years later.

Kuromiya’s memoir voices his disappointment with other Nisei. He felt that many Nisei had abandoned Japanese culture because of their desire to be recognized as loyal Americans, so much so that, according to him, they had come to view their Issei parents as liabilities. He was critical of his generation for not becoming involved in the social change that occurred in the 1960s and 1970s. He accuses them of choosing “to play it safe by striving to become a self-proclaimed ‘model minority.’” Yet, at the same time, he believed that it was the shikata ga nai (“it can’t be helped”) culture that had caused JAs to yield to the government’s unconstitutional actions against them.

Kuromiya was even more disappointed with the JACL. He correctly pointed out that during the war, the organization had helped the government identify Issei who might have been spies for the Japanese government. Moreover, the JACL had taken the position that “loyalty” to the US meant complying with whatever the government said or did, regardless of constitutional issues.

As a result, resisters like Kuromiya became pariahs in the JA community. He believed that the JACL’s stance had led many JAs to decide it was “best to let sleeping dogs lie” by not speaking out.

Letting sleeping dogs lie was not something that Kuromiya believed in. He continued to speak out. Even in the late 1990s, after the JACL apologized to the draft resisters, whom it had denounced during and after the war, Kuromiya felt that the apology was insufficient. In his opinion, the JACL owed an apology to all JAs.

Kuromiya also was dissatisfied with the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. That Act had declared that the WWII incarceration of JAs was “a grave injustice” and granted reparations to all survivors of it. Kuromiya’s disappointment arose from the fact that the Act essentially nullified a class action lawsuit filed by the National Council for Japanese American Redress. That suit sought not only more substantial reparations. More importantly to Kuromiya, it sought a judicial declaration that would have prohibited the government from engaging in the unconstitutional and illegal conduct done to JAs with other ethnic groups.

Despite these sentiments, the book’s appendix contains an essay that Kuromiya wrote in the early 2000s. There he reiterates his belief in the FPC’s idea that each citizen has an “inescapable primary duty” to challenge in court government policies that blatantly violate the Constitution. Nonetheless, he concludes:

“But through subsequent acts like the presidential pardon of convicted draft resisters, the success of the coram nobis cases (that exonerated Fred Korematsu, Minoru Yasui and Gordon Hirabayashi, and in the Korematsu and Hirabayashi cases recognized that misconduct and racial bias led to the government’s actions), and the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 with the historic acknowledgment by the government of its massive civil rights violations, I feel our actions in placing our faith in the U.S. Constitution and the basic principles of our democracy have been more than vindicated. As the saying goes, ‘With so much manure, there HAD to be a pony in there somewhere.’ Happily, I think we found the pony.”

Perhaps in the 57 years that had passed since Kuromiya resisted the draft, he had finally come to terms with all that had happened before.

Sadly, the rift between JAs who resisted and dissented from the government’s actions and those who disagreed with them was never completely repaired. But over the years, many JAs today have come to believe that the Nisei dissenters—whether draft resisters, no-no boys or others who used the courts to protest against unjust measures that the government imposed on them during the war—were simply exhibiting patriotism and bravery in a different manner than the Nisei who served in the 100th Infantry Battalion, the 442nd Infantry Regiment, and the Military Intelligence Service (MIS). Those of us who think this way believe that the soldiers, the dissenters and the resisters all deserve our respect and admiration.

© 2023 Pamela A. Okano / The North American post