One of the splendors of the city of Detroit is the Detroit Art Institute, a museum that boasts collections of painting, sculpture and objects drawn from around the world. A special highlight is the museum’s interior courtyard, site of the Detroit Industry murals. This series of 27 frescos, commissioned by museum director Wilhelm Valentiner with financing from automobile baron Edsel Ford, was created between 1932 and 1933 by the renowned Mexican artist Diego Rivera, who is said to have considered the work his finest achievement. The murals are comprised of two main panels that portray industrial laborers at the Ford Motor Company’s famed factory complex at River Rouge, along with a series of smaller adjoining panels.

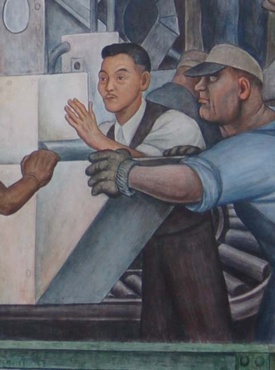

One scene in the mural depicts a group of black and white workers laboring together, their bodies caked with grease and dirt. Among them stands a man in white shirt and tie, whose face is unmistakably Japanese, and who is directing the crew.

The Rivera mural invites us to explore the hidden stories of the real-life man behind the image, engineer Masao Hirata, as well as the other Japanese who came to work in Detroit at the dawn of the 20th century and helped build the American auto industry.

One of the earliest Japanese in Detroit was Kaju Nakamura. According to a 1911 article in Los Angeles Times, he served an apprenticeship in Detroit with the Studebaker company on the E-N-M line. Nakamura thereafter sailed to Asia, where he took a position as a Studebaker dealer—the first native-born Japanese to sell and service American cars in Japan and China.

According to multiple sources, the first Japanese immigrant to actually settle in Detroit and work in the auto industry was Tadae James Shimoura. Born in Tokushima Prefecture, Japan in April 1885, he immigrated to the United States in 1912. By working as a coal stoker on ships, he both paid his passage and became acquainted with English. At first Shimoura travelled to Reading, Pennsylvania, where the Acme Motor Company was based. He met Acme’s president James Hervey Sternbergh. When the young Shimoura told Sternbergh that he wished to study automobiles, Sternbergh replied that he would do better to head to Detroit and check out the Ford Motor Company, which was developing its epochal assembly line process. Shimoura went to Detroit and met Henry Ford, who was delighted at the idea of a Japanese disciple, and who offered to allow Shimoura to go to any department of his factory and study for two years as a research student with Ford’s brother-in-law Milton Bryant.

In 1914, Shimoura’s two-year research period ended. The young man received an offer from Ford to concentrate on studying Jeeps and developing them further. However, Shimoura did not wish to work as an engineer in the greasy plant surroundings, and he instead took a job as a chemist at the Ford Chemical Laboratory. When the Ford Company thereafter bought land in the Amazon region of South America and began producing rubber, Shimoura was commissioned to undertake research on the rubber.

In 1931, in the depths of the Great Depression, the Ford laboratory faced cuts and layoffs. Though Shimoura had spent 21 years with the company and had greater job security, he resigned and began his own chemical business. Sometime around 1940, he created the Oriental Provision Company, which did wholesale grocery supply and catering. Shimoura’s wife Tsugi (a Waseda University graduate) and their four children appear to have helped in the business.

In 1971, near the end of his life, Shimoura and his wife were interviewed by the Detroit Free Press about their memories of the Pearl Harbor attack and the coming of the Pacific War. Shimoura recalled that he and the approximately 100 other Japanese nationals in Detroit faced suspicion and FBI raids. However, he offered praise for John S. Bugas, the head of the Detroit FBI, who he said had made sure that all Issei questioned by the FBI were treated courteously, with dignity, and were permitted to continue working in Detroit once their questioning was completed.

Throughout the war years, Shimoura continued to drive daily into war plants to provide supplies. According to author Rev. Gordon Nakayama, in a 1947 article in the Japanese Canadian newspaper The New Canadian, Shimoura’s business so prospered during this period that he owned three personal cars, as well as a fleet of delivery trucks. Mrs. Misao Kawamoto, who lived in Detroit in the 1950s, reported that Shimoura, by then in his 70s, was still working as a wholesaler who concentrated materials to make chop suey, which he sold to stores and hospitals.

James Shimoura retired from business in the late 1950s. In 1960, he honored by the Japanese government as one of the Issei pioneers who had contributed to better relations between Japan and the USA. James Shimoura died in Detroit in 1979. His family remained in the Detroit area after his death. His grandson James Shimoura would later serve as attorney for the family of Vincent Chin, the young Chinese American killed in a racist hate crime in Detroit in 1982.

In addition to his own career, James Tadae Shimoura helped make possible the entry of other Issei into the auto business. Shortly after arriving in Detroit, Shimoura recommended to Ford a friend from Japan, James Koichi Sasakura, who was duly hired as a research student. Born in Kobe, Japan in 1890, he emigrated to the United States as a young man. After his research stint, Sasakura would work for Ford for a time before going elsewhere. He would became legendary in Detroit for his ability with machinery. Working for the Ex-Cell-O corporation, he designed the machinery that forms and seals waxed milk cartons.

According to one source, he joined Tucker Motors to help develop the Tucker automobile (The Japanese character “Jimmy” in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1988 film Tucker: The Man and His Dream, portrayed by the actor Mako, is based on Sasakura). Sasakura married Charlotte Gilbert, who died in 1937, and four years later wed Chiyoko Matooka. James Koichi Sasakura died in January 1952.

James Shimoura also recommended to Ford a young engineer named Masao Hirata. Hirata, born in Japan on January 18, 1887, had arrived in the United States in the early years of the 20th century—like many of the young Issei men who emigrated during that time, he may have been seeking to escape conscription in the Russo-Japanese War. After his period as a research student, he became a full-time employee at the Ford company, and worked there for forty years.

Just what Hinata did at Ford is a matter of some uncertainty. He was generally described as a “tool and dye maker.” According to another source, he was assigned as a special technician in charge of all the glass rooms that contained precision gauges. Whatever it was, he was a sufficiently valued employee for his presence to be immortalized in Rivera’s mural, though it is uncertain whether he was recommended by his superiors or whether Rivera himself hit on the idea of including him. (Rivera would form a number of close connections with Nikkei artists, notably Foujita and Isamu Noguchi, and would later engage painters Hideo Noda and Mine Okubo to work as his assistants on mural projects).

Hirata also was featured in the nationwide press in 1938, when he appeared in a “Parade of the Nations” at River Rouge, and was photographed wearing Japanese costume alongside workers from diverse other nations in their native dress.

With the coming of World War II, Hirata became an “enemy alien” and faced restrictions on his employment. It is not clear whether or not he was actually laid off by Ford for a period—his draft card from early 1942 identifies him as an employee of Baldwin Harbor Works. Whatever the case, he was hired by Ford for work as an expert with Johannson gauges working on the B-29 bomber at the new Willow Run plant. According to one source, the government was uncomfortable with a Japanese immigrant working at the plant, but company director Edsel Ford insisted, “If I can’t have...Hirata working for me, you might as well shut down the plant.” Still, due to his status, Hirata was subjected to constant surveillance by the FBI. It may have been because of such harassment that sometime during this period, he adopted the American name “Jim.”

Following World War II, Hirata expressed his intention to retire from Ford, but company executives asked him to stay on, as there was no other worker who could take his place.

Thus it was that he served as guide to Eiji Toyota, legendary president of Toyota Motor Company, when the Japanese executive made a study tour of the Ford plant some five years after the end of the war. In 1953, around the time that he became a naturalized U.S. citizen, Hirata left the company and moved to Florida. Shortly after joining Ford, he married Martha Garber, an American from Pennsylvania. Their daughter Mildred Hirata was born some years after. After his wife Martha died, Hirata married Ellen Harber (apparently his late wife’s sister)

Another early Issei who worked in Detroit was Hachiro “Hatch” Kitamura. Born in Osaka, Japan in 1889, Okamura was the son of acrobats and circus performers. In 1898 his parents decided to move the family West, and try their luck as performers. The young Hachiro accompanied his parents and seven siblings to the United States, where his parents joined the B.E. Wallace Circus, They thereafter went to Europe, where the Kitamura family toured as headliners, then were featured in the famed Buffalo Bill Wild West show. After the family returned, they spent the following years touring in vaudeville. In 1916, the young Hatch married Edith Reed, a native of Michigan, with whom he would have four children.

By 1918 the young Hatch had formed his own troupe, the “Hatch Kitamura Japs,” a troupe of three tumblers. They toured Canada, receiving rave reviews in Calgary and Vancouver, then headed on to Wisconsin, Kansas, Nebraska, Texas and Arkansas. Still, he clearly had had enough of show business, as in 1919 he joined the Dodge division of the Chrysler corporation, where he remained as a laborer for 35 years. In August 1954, shortly after he became a naturalized U.S. Citizen, Kitamura retired. He later moved to Marine City, and he died in 1972.

It is perhaps symbolic that Linda Bank Downs’s 2016 book Diego Rivera: The Detroit Industry Murals, which can claim to be the definitive work on the Detroit Art Institute’s landmark artwork, does not once mention Rivera’s depiction of Masao Hirata. The contributions of Hirata and the other Japanese in Detroit remain understudied. To be sure, the available sources that I have found on them are rather incomplete, but even what I have turned up suggests that we need to broaden our understanding of the early history of the American auto industry to reflect their presence.

© 2023 Greg Robinson