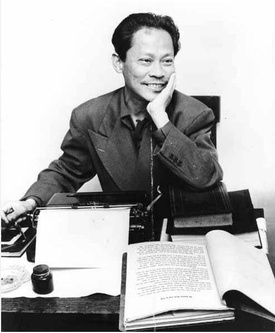

One of the first and most gifted writers to express an Asian American consciousness was Carlos Bulosan. Bulosan’s experience as a migrant laborer from the Philippines to the U.S. and his travels along the California coast during the era of the Great Depression inspired his work, most notably his autobiographical novel America is in the Heart (1946). The novel introduced the experience of Filipino migrants to American audiences. Bulosan’s incisive portraits of migrant farmworkers provided one of the first accounts for a mainstream audience of the prejudice and hardships that Filipino Americans faced in the “Land of the Free.” While America is in the Heart is considered Bulosan’s magnum opus, his larger corpus of writings, both fiction and nonfiction, is notable for embracing multiple genres and viewpoints.

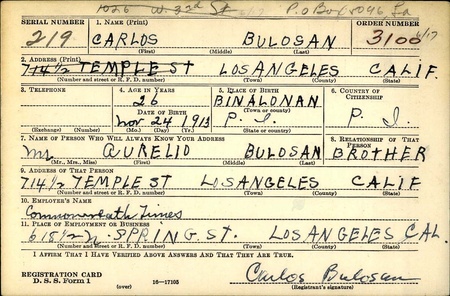

Born on November 24, 1913 in Binalonan, Philippines (the date later listed on his draft card), Carlos Sampayan Bulosan spent his youth living on his family’s farm. Like the vast majority of Filipinos outside the American-backed elites who controlled much of the nation’s wealth, Bulosan grew up in poverty.

On July 22, 1930, Bulosan migrated to the United States, hoping to find greater economic opportunity (the Philippines being an American colony at the time, its nationals enjoyed free entry to the mainland). Bulosan arrived in Seattle, where he was recruited to work in the Alaskan fish canneries, alongside Japanese American workers. He soon returned from Alaska to Seattle, then spent the subsequent years moving around the states of Washington and California working as a farm laborer, harvesting grapes and asparagus, and working as a dishwasher and at other odd jobs.

All along the West Coast, he faced relentless discrimination as a Filipino and witnessed the harsh effect of racism on Asian Americans, a set of experiences that would be recounted in America is in the Heart. In 1938 Bulosan helped form a new cannery workers union, the United Cannery and Packing House Workers of America (UCAPAWA), under the CIO. It represented fish cannery and packing house workers.

The period before World War II proved to be foundational for Bulosan, as he developed a political consciousness as a leftist writer. Bulosan began frequenting the Stanley Ross bookstore in Hollywood, where he met noted writers Carey McWilliams and Louis Adamic. Bulosan personally cited McWilliams and his book, Factories in the Fields, as an inspiration for his own writings. McWilliams, in turn, would provide an introduction for the first edition of America is in the Heart.

In 1934, Bulosan was named editor of The New Tide, a short-lived radical proletarian literature magazine. During these years, he began working for several Filipino community newspapers in Los Angeles, such as the Philippine Commonwealth Times and Manila Herald.

In 1936, Bulosan contracted tuberculosis, and was forced to spend two years convalescing in a hospital in Los Angeles. During this period, he began to read incessantly to improve his writing skills, and started writing poetry.

Following U.S. entry into the Pacific war in December 1941, Bulosan became active in supporting the U.S. war effort to liberate the Philippines, where his family members lived. In his speeches and articles in support of the war effort, he repeatedly referenced his brother’s capture by Japanese military forces at Bataan.

His political platform remained wide. In November 1942 he participated, as a representative of Philippine Americans, in a salute to Russian art that marked the 25th anniversary of the founding of the Soviet Union. In October 1943 he attended a Writers Congress held by the League of American Writers at UCLA, and spoke together with Carey McWilliams and NAACP Director Walter White at a “Minority groups” session (the session was chaired by UCLA professor Leonard Bloom, a leading supporter of Japanese Americans).

In February 1945, Bulosan was invited by the California Council of Republican Women to speak in Los Angeles on the occasion of Washington’s Birthday, with the subject being “George Washington in American Freedom.” (An article on the meeting in The Los Angeles Times made what is perhaps the first public reference to Bulosan as author of America is in the Heart, a book then in the works).

As in the case of other leftist writers and writers of color, Bulosan’s activities were monitored by agents of the FBI (his FBI file can be found on the website of the University of Washington). The FBI monitored Bulosan for a variety of reasons, ranging from his alleged membership in the Communist Party USA to his writings discussing racial discrimination.

One page in Bulosan’s file contains a report from an informant who had attended the Writers Congress at UCLA in October 1943. The informant reported a portion of the speech that Bulosan gave there, which he described as extremely moving and free from bitterness:

“You want to see an American Filipino soldier? Well, here is one. My body and mind are here. I have left one leg and a brother and a sister dead in Bataan…”

In addition to his speeches, the war era saw Bulosan break into mainstream periodicals, including The Saturday Review of Literature, Writer, and Scholastic, as well as the Leftist journal New Masses. Some of Bulosan’s most remarkable contributions from the wartime period are pieces that were published in mainstream magazines. In his article “Letter to a Philippine Woman,” which ran in The New Republic in November 1943, Bulosan underlined his inclusive vision of life in America:

“It is but fair to say that America is not a land of one race or one class of men. We are all America that have toiled and suffered and known oppression and defeat, from the first Indian that died in Manhattan to the last Filipino that bled to death in the foxholes of Bataan…America is also the nameless foreigner, the homeless refugee, the hungry boy begging for a job and the black body hanging from a tree.

America is the illiterate immigrant who is ashamed that the world of books and intellectual opportunities is closed to him. We are all that nameless foreigner, that homeless refugee, that hungry boy, that illiterate immigrant and that lynched black boy. All of us from the first Adams to the last Bulosan, native born or immigrant, educated or illiterate—We are America!”

Around the same time, Bulosan was commissioned by The Saturday Evening Post to contribute to a series of essays inspired by President Roosevelt’s January 1941 “Four Freedoms” speech. In March 1943, the Post published Bulosan’s essay on “Freedom From Want,” which it placed alongside Norman Rockwell’s famous image of a family at Thanksgiving. In the essay, Bulosan affirmed that the meaning of freedom was “that all men, whatever their color, race, religion or estate, should be given equal opportunity to serve themselves and each other according to their needs and abilities.” Yet he went on to link strongly the spiritual and material dimensions of liberty:

“So long as the fruit of our labor is denied us, so long will want manifest itself in a world of slaves. It is only when we have plenty to eat—plenty of everything—that we begin to understand what freedom means. To us, freedom is not an intangible thing. When we have enough to eat, then we are healthy enough to enjoy what we eat. Then we have the time and ability to read and think and discuss things. Then we are not merely living but also becoming a creative part of life. It is only then that we become a growing part of democracy.”

Although Bulosan’s essay was picked up by the Treasury Department and the Office of War Information to help sell war bonds, and reprinted in different media, it has been generally omitted from later editions of the Norman Rockwell series.

Bulosan was also active in writing for newspapers during the war era. He continued to contribute columns to Manila Post Herald and to a new publication, the The Philippines-Bataan Herald. In a piece for The Philippines-Bataan Herald celebrating V-J Day, Bulosan expressed his powerful sense of solidarity with other Asian Americans and other minorities.

“I sit here listening to the song of American freedom in the voices of many races—Anglo-Saxon, Filipinos, Mexicans, Chinese, Koreans, Negroes—Americans all, and immigrants all, but all lovers of freedom and equality.”

Meanwhile, In 1943 he sent letters to the Lompoc Record newspaper to remind its editors of his presence, explaining that he had been a dish washer in Lompoc and considered it his hometown. After noting his authorship of “Freedom from Want,” he added:

“This fact does not mean anything to you if you do not know that it was in Lompoc where I grew up. When I arrived from the Philippines some twelve years ago, I went to Lompoc and resided there for almost two years. I worked on the farm there, and also at the café called ‘Lind’s Café.”

Bulosan would write his “hometown” newspaper twice more in the following months to recount his news. His letters allowed him to revel in the success of his work and remind them of the need to pay attention to their nonwhite residents, in the process tacitly reproaching the town for ignoring him in his years as a young immigrant there.

During the war years, Bulosan also started publishing books. In 1942, he published a pair of volumes of poetry with small houses. Chorus For America: Six Filipino Poets, put out by Wagon and Star Publishers in Los Angeles, featured poems by Bulosan and five other poets of Philippine ancestry. A solo book of poems, Letter from America, followed soon after with the. Press of J.A. Decker in Illinois.

The Voice of Bataan, published by Coward-McCann in 1943 under the auspices of the American-Philippine Foundation (an organization which Bulosan served as vice president), was a cycle of Bulosan’s poems on the ordeal of the Philippines under Japanese occupation. It carried a preface by General Carlos Romulo, a statesman and author who soon after became “Resident Commissioner” (i.e. non-voting delegate) of the Philippines to the US House of Representatives.

Despite his posthumous reputation as a writer on racism, war, and other such serious subjects, Carlos Bulosan’s best-known works by far during his lifetime were his humorous sketches about his childhood in the Philippines. These works, written on the model of the Life with Father stories by Clarence Day, offered a light-hearted but loving portrait of the author’s family, from whom he was cut off by the war.

Beginning with the story “Laughter of my Father” in 1942, he published a half-dozen of these in The New Yorker. Bulosan then collected the stories into a book, which was published under the title Laughter of My Father in 1944 by the publishing house Harcourt Brace. It was widely reviewed, and the author received numerous plaudits for his talent as a storyteller and domestic humorist. Excerpts from the book appeared in Louis Untermeyer’s popular anthology A Feast for Laughter, while Bulosan’s sketch “My brother Osong’s Career in Politics,” was included in the prestigious anthology, The Best American Short Stories 1945.

Ironically, it was Bulosan’s success as a creator of humorous sketches that catapulted him to fame and that led Harcourt Brace to approve publication of his fictionalized memoir, America Is In the Heart, which appeared in 1946. Although the novel received respectful reviews upon publication in 1946, it did not sell well.

In the years after publication of America Is In the Heart, Bulosan reduced his literary work and concentrated on union organizing, notably with the International Longshore Workers Union. In 1953, Bulosan was elected Educational and Publicity Director of ILWU Local 937, a local with mostly Filipino members.

Duing these years, he faced blacklisting and poor health. He spent his final years in Seattle in and out of hospitals, and died in 1956 (according to his friend, union leader Chris Mensalvas, Bulosan died from a combination of tuberculosis and malnutrition).

© 2022 Jonathan van Harmelen; Greg Robinson