Harry Kitano writes in his book Generations and Identity: The Japanese American that "the early Christian missionaries in Japan were unsuccessful in their mission work, and the Japanese immigrants who came to America were a good target for them to evangelize." However, Kitano's analysis does not really apply to the Japanese in Chicago. It seems as if he is saying that it was the success of mission work in Japan that led Japanese people to Chicago. One such person is Ogawa Michitaro, also known as Ongawa Michitaro.

Michitaro Ogawa came to Chicago in April 1871 at the age of 12. He was brought there by Julia Carothers, the wife of a Presbyterian missionary, Christopher Carothers, when she returned to the United States from Japan for a short time.

Carothers graduated from the University of Chicago in 1867 and Presbyterian Theological Seminary in Chicago in 1869, and traveled with Julia to Yokohama. The missionaries lived in the Yokohama concession and taught English and Christianity to the Japanese. Michitaro was one of Julia's students.

The church was planning to send the talented Michitaro back to Japan after he had been trained as a missionary in the United States, so Julia left him in the care of her father, Richard Dodge, who was also a Presbyterian minister, in Madison, Wisconsin. After a year's leave, Julia returned to Japan to be with her husband, leaving Michitaro behind.

Around this time, a group of four Japanese students came to the University of Chicago. They were led by Matsudaira Tadakazu, the former lord of the Shimazu clan, and had a letter of introduction from Carothers. There is a record that they attended partial courses in the Collegiate Department at the University of Chicago for one semester in the spring of 1872.

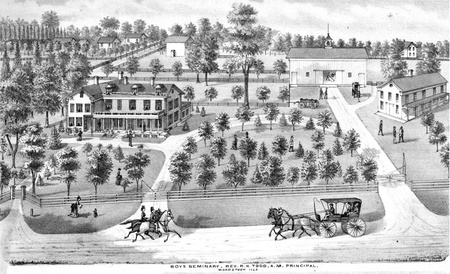

Michitaro lived under Reverend Dodge in Madison, Wisconsin for only about a year. In 1872, the year after taking care of Michitaro, Reverend Dodge was "transferred" to San Francisco, so he sent Michitaro to the Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, Illinois. This school was opened by Reverend Richard Todd, who, like Reverend Dodge, had graduated from Princeton Theological Seminary in New Jersey. Michitaro spent about five years there.

According to Julia, Michitaro liked to please people and was quite popular at school. During his time at the Todd School, Michitaro was invited by church officials to give many lectures. For example, at a lecture held on May 24, 1877 at Hershey Hall in Chicago, sponsored by the Ladies Foreign Missionary Board, Michitaro praised the work of female missionaries.

After graduating from the Todd School in 1878, Michitaro is recorded as enrolled at Lake Forest College, a Presbyterian college located north of Chicago, and at the University of Chicago in 1879, but it is unclear whether he graduated from either school.

The 1880 census recorded the first Japanese living in Illinois, and one of the three was Michitaro. At the time, Michitaro was 21 years old, single, and worked as a company clerk. In 1884, he obtained citizenship, becoming the first naturalized Japanese citizen of Illinois. At the time, naturalization was possible after five years of residence in the United States.

Did Michitaro, when he grew up, actually become a missionary as the church had hoped?

No. While working as a clerk in a bank and the Chamber of Commerce in Chicago, Michitaro began to pursue a career as an entertainer who "pleases people," rather than as a missionary. The catalyst for this may have been his meeting with Clara Page, a white woman who was a music teacher, and their marriage in 1891.

Clara was well known in the music world in and around Chicago, having appeared in the opera "The Mikado" in 1896, founded a Beethoven club in Austin, and directed a church chorus.

Around 1909, Clara was hired as a teacher at the Bliss School of Music to teach singing and harmony, and the couple moved to Oak Park, famous for the home and studio of architect Frank Lloyd Wright, while Michitaro was still working at the bank.

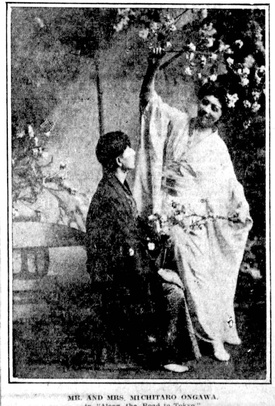

It was around the beginning of the 1910s. Pushed by the popularity of Japonism at the time, the two began to introduce Japanese culture and life to the Japanese by wearing kimonos, singing in Japanese, playing the shamisen, dancing, and performing musical-style plays in English. In 1913, they began touring towns in the Midwest, including Iowa, Missouri, and Kansas, performing their own English play, "Along the Road to Tokyo," which resembled the world of Lafcadio Hearn. Perhaps the combination of a white woman and a Japanese man was unusual. Their performances were so popular that they also participated in the Chautauqua mass education movement, which was popular from the early 20th century to the 1920s, signing a contract with a promotional company and touring the United States.

They expanded their repertoire with original plays such as "A Glimpse of Japan" and "Japanese Sketch," and in the 1920s, their plays were increasingly performed at higher educational institutions across the United States, including Columbia University in New York, the University of North Carolina, and Rice University in Texas. The Ongawas were what we would call multicultural education trainers today, and were pioneers of today's multicultural education.

What is interesting about Ongawa Michitaro is when we think about when he learned Japanese songs, dances, and the shamisen. When he went to America at the age of 12, he must have already acquired a basic set of skills. It is hard to imagine a 12-year-old boy going to America with a shamisen, and when we wonder where Michitaro got his shamisen, we can see that he may have been quite connected to the Japanese community in Chicago, though at a distance. In fact, it seems that Michitaro would occasionally show up at parties attended by the Japanese consul and small Japanese gatherings.

And then there's Clara. It must have been Michitaro who taught her Japanese songs, dances, and the shamisen. But was it difficult to learn? What kind of plays did the two of them perform? Am I the only one who is intrigued and wants to see what they were like over 100 years ago?

There is a Japanese man who met Ongawa Michitaro. Inoue Orio, who studied at the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago around 1899, said the following about Michitaro in New York 20 years later:

"He went overseas at the age of 12 and has been in America for over 30 years, so it is not surprising that he does not know Japanese. At the same time, he has completely forgotten Japan, his only uncle, and, in fact, that he himself is Japanese. From the standpoint of assimilation, this may be ideal, but I cannot hope that the children of our Korean compatriots in America will grow up to be like this in the future."

Masutō Kono, who came to Chicago in the 1920s and ran a restaurant, also noticed that Japanese people in Chicago were not very interested in teaching their children Japanese. What does Japanese mean to someone who lives with the feeling of being "alone in white society" as if it were a part of his or her body? Of course, each person will have their own answer. The diversity of answers may be what it means to live in America.

There is no gravestone in the cemetery number, section 43, lot 113 S1/2, given to me by the management office of Forest Home Cemetery in Forest Park, west of Chicago. Ongawa Michitaro was born in Tokyo on February 21, 1869, and died in Chicago on July 30, 1938, at the age of 79. A small, empty patch of ground that no one knows about is the grave of the first Japanese person to settle in Chicago.

During and after the war, Forest Home Cemetery decided to refuse burials of non-whites. The absence of a gravestone for Michitaro may have been the result of the removal of the gravestone. Even if that was the case, I stood on the soil where Michitaro was buried and put my hands together in prayer, believing that the "international marriage" of the first Japanese to settle in Chicago and bury his bones there was a happy one, fitting for Chicago, a metropolis built on the dynamism of immigration.

*This essay is based on the English version of " Michitaro Ongawa: The First Japanese American Chicagoan " (December 7, 2016).

© 2022 Takako Day