In 1912 Los Angeles, Leo Kumataro Hatakeyama, a Catholic veteran of the Russo-Japanese War, wrote to his bishop in Japan that he wanted to confess his sins by registered mail as he could not find a priest in his area who could understand his native Japanese language. Instead, Hakodate Bishop Alexander Berlioz, MEP sent Japanese-speaking Fr. Albert Breton to serve the 50 or so Catholic Japanese in Los Angeles. This mission work would be handed over to the Maryknoll Fathers in 1921. The Japanese Catholic Center remains active at 222 S. Hewitt Street in Little Tokyo.

Maryknoll is the first Catholic Congregation of Americans focused on foreign missions, although Little Tokyo is not “foreign.” In 1900, there were 17,000 Catholic priests in the United States with only 16 serving in other nations.1 The Catholic Mission Society of America, or the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers, was established in 1911, and the Maryknoll Sisters was established in 1912. Both are now headquartered in Ossining, about 40 miles north of New York City.

Southern California’s fresh air and warm weather were already attracting health seekers by the 1870s. Particularly, Dr. Francis Marion Pottenger’s 1910 Sanatorium in Monrovia would stand out. Dr. Pottenger determined that good nutrition, including fresh orange juice, rest, and the dry weather in the citrus groves along the San Gabriel Mountains was good for consumption—or tuberculosis—patients. Eventually, the 40-acre Pottenger Sanatorium gave hope to tuberculosis victims around the nation. By 1911, there were 23 such sanatoriums in California, many along the San Gabriel foothills in northeast Los Angeles.2

A devout Catholic and Japanese American doctor, Daishiro Kuroiwa, seeded Maryknoll $10,000 to find a tuberculosis sanatorium that would accept and treat patients of Japanese descent. In 1940, it was estimated that there were 500 Japanese American tuberculosis patients in the area.3 A letter from Maryknoll Fr. Lavery to Ossining, dated 29 Dec 1927, reads in part:

Because of hard work and improper food, many Japanese in this country become victims of the white plague. Recently Dr. Kuroiwa, one of my Catholic parishioners, discussed the situation with me here and brought out some facts that might interest you. One reason he assigned for the Japanese people not improving rapidly under the treatment given in State and County institutions is because they are obliged to eat American food there.4

Did this collaboration with Maryknoll exist, because the Japanese community was already battling the Alien Land Act in trying to establish the Japanese Hospital in Boyle Heights? In 1928, the case of Jordan v. Tashiro was decided in the U.S. Supreme Court. The 42-bed Japanese Hospital opened in 1929 at 101 S. Fickett. Interestingly, Dr. Kikuwo Tashiro later contracted tuberculosis and was himself a patient at the Maryknoll Sanatorium during the war years.5

After a 10-year search, Maryknoll Sisters took over the 15-bed Monrovia Sanatorium then at 727 Oak Park Lane (now 300 Norumbega Drive), previously owned and managed by Katherine Decker.6 It was renamed Maryknoll Sanatorium by 1932 and run by five Maryknoll Sisters under Sr. M. Edward Diener. Adjacent property and avocado groves were added on, and it expanded to 50-bed capacity on seven acres.

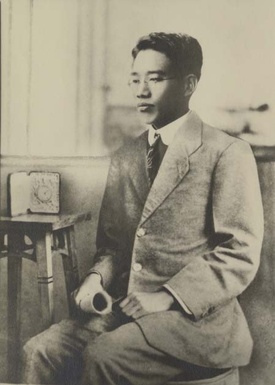

concentration camp, California, ca. 1944. (Photo courtesy of Maryknoll Mission Archives)

World War II’s Executive Order 9066 mandated the internment of Japanese Americans in the West. LA County authorities and the War Relocation Authority deemed 175 Japanese Americans too sick with tuberculosis to be moved. These individuals were isolated at the Hillcrest La Crescenta facility and the Maryknoll Monrovia facility – guarded by armed sentry.7

There were two Maryknoll nuns of Japanese descent: Sister M. Bernardette Yoshimochi and Sister M. Susana Hayashi. Both nuns chose to stay with their congregation rather than transfer to Ossining, New York and out of the reach of FDR’s evacuation order. The two Catholic nuns continued their service at the Manzanar Orphanage.

Maryknoll Father Hugh Lavery led other support efforts for Japanese Americans in these trying war years. Maryknollers helped Los Angeles Japanese organize for the evacuation, visited them at various camps, wrote letters of support, and helped families re-establish once the Japanese Americans were released.8

Another story should be told about the Maryknollers who managed a hospital in Kansas City, also not a “foreign” location. Maryknoll Sr. Madeline Marie Dorsey wrote, “On May 22, 1955, Queen of the World Hospital opened its doors to the sick of all creeds and races.”9 It was the first hospital in the region intentionally with two African American doctors, several Black nurses, and more to come. Sister Madeline Dorsey was also on the front lines of the 1965 Selma March and the 1970s El Salvador Civil War.

By the early 1950s, the original cottages of the Monrovia Sanatorium were deteriorating and new vaccine and antibiotics were slowing tuberculosis. In 1958, a new hospital facility was built. Maryknoll Hospital served the community until 1972 when it became a retirement center for Maryknoll Sisters. Maryknoll site in Monrovia reminds us of the long path it is taking to get healthcare—“to the sick of all creeds and races.”

Notes:

1. Harry Honda, “The Maryknoll Story in Little Tokyo,” Presentation to the Little Tokyo Historical Society on March 24, 2007, Los Angeles.

2. Lyra Kilston, “Dr. Southern California: Heading West for the Cure,” Cabinet Magazine, Spring 2018-Winter 2019.

3. Brian Niiya, “Hillcrest Sanitarium,” Densho Encyclopedia. Accessed June 3, 2022.

4. Private letter from the Maryknoll Mission Archives. Special thanks to Professor Mariko Omori, Hiroshima University.

5. Kristen Hayashi, “Kikuwo Tashiro,” Densho Encyclopedia, last updated Jan. 2021. Accessed June 3, 2022.

6. “Sister Louise Deiner, MM” Maryknoll Mission Archives. Accessed June 3, 2022.

7. Brian Niiya, “Hillcrest Sanitarium,” Densho Encyclopedia. Accessed June 3, 2022. Also “Act to Move Japanese from Two Hospitals” in Pacific Citizen, May 20, 1943, 6.

8. Jonathan van Harmelen, “Japanese Culture and Catholic Faith: Maryknoll’s Long History in Little Tokyo,” Rafu Shimpo, April 1, 2021. Van Harmelen also wrote about Sisters Bernadette Yoshimochi and Susanna Hayashi, and Father Hugh Lavery.

9. Vicky Diaz-Camacho, “How One Kansas City Hospital Treat Segregation in the ‘50s,” Flatland, February 20, 2019.

© 2022 Susie Ling