Trades

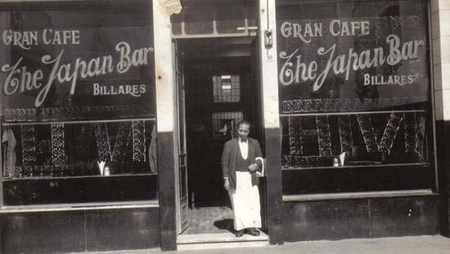

The trades carried out can be differentiated between those who settled in the cities and those who decided to go to the countryside. In the case of Salta, the jobs that predominated were cafes, dry cleaners, floriculture and work on farms (in the interior of the province). In the case of coffees, it was one of the most notable works of the Japanese during the 1920s. In Salta, there is a record, according to interviews, that there were several cafes where the Japanese owners hired their compatriots as waiters. Among those that can be named is the best known, “The Japan Bar”, by Minwa Higa, located at that time at Alberdi n° 90. The “Japanese Café”, by Kioshi Uchino; “Café Japonés”, by Tokichi Maehashi, located at Miter 283 and, finally, “Café Japonés”, by Mori Ryoshiro and Tai Yohei 1 . The best known, and where most of the migrants who had arrived in Salta were employed, were Minwa Higa and Tokichi Maehashi.

On the other hand, dry cleaners were one of the jobs that marked the Japanese community in all parts of the world. It had its beginnings in the 1920s, along with cafes, maintaining its success until the 1980s. To this day, very few are still active.

A good indicator of the success that the dry cleaners had is due to the fact that both the receiving society and the newcomers would move towards the development of a middle class whose formation was just hinted at (Leumonier, 2004). This responded to the typical phenomenon of the Japanese community and formed the basis of its achievements:

- Family labor contribution: it was very common for the entire family to work in the same field, thus both wife and children helped in the business. The contribution of the children was important in maintaining the family business (cafes or dry cleaners), although the Nisei began to access university degrees, thanks to the efforts of their parents. Furthermore, the economic and political circumstances at that time, along with the rights and contributions that they had to give to employees, was a difficulty for them, so they decided that the family circle would take over the business. It happened that many cafes closed because they could not keep employees.

- The call to compatriots: yobiyose 2 or “migration by call”, occurred mostly from 1923, the year the migration contracts ended, until 1936, when a decree was issued that established a limit number of immigrants per nationality. This type of migration occurred when the migrant achieved a better economic situation and called his family and friends to come, dividing into two modalities: the call of relatives and friends, and that of portrait marriage (shashin kekkon), in which which the spouses only knew each other through photographs. One can name the case of Seizo Hoshi, who had fellow citizens brought from Japan with the idea of creating an artificial paradise, spoken in Japanese, in the province of Mendoza.

- Closed circle loans: better known as tanomoshi, they consisted of a loan that was made between the Japanese themselves to be able to establish their own businesses. This group savings system allowed one member of the community to be financed each month and generated more confidence among them, especially for some who could not access bank loans.

- A quasi-mystical conception of work: the Japanese sought to raise capital to start their businesses, which shows how the issue of work is something more cultural for them. Thanks to all these efforts, they were going to be able to move forward and advance or, as they wished, “climb socially”, and this was the way the receiving society saw them, as a hard-working and effective community.

In Salta they set up dry cleaners with the capital they had been able to raise. The first ones who opened their businesses hired others, where they taught them the trade and thus they acquired experience and money until they could establish their own business. Among these cases we can name that of Tadashi Matsumoto, who worked with the Hamasakis for a time and then settled in Oran and opened his dry cleaning business, which remains to this day, but is managed by one of his sons.

Then, there is the case of Isamu and Mariko Hamasaki, Suminori's niece, who already had a dry cleaning shop. They worked there until they were able to establish themselves and open their own business, which is currently located at Balcarce 415, where she and her son run it. On the other hand, dry cleaners such as Suminori Hamasaki (Alvarado 956), Gensei Higa (Caseros 1725), Buhei Uchino (Acevedo 281) and Kana Ikehara (Rivadavia 962) are still active. Others were closed over time, due to the fact that no one could continue with the family business or they did not have the capital to maintain it, as happened with that of one of Saburo Onaga's sons. Currently, these dry cleaners are already run by the children or grandchildren of migrants.

In the case of those who settled in rural areas, such as Salta, the migrants went to the interior of the province, but they did not form colonies, as occurred in other provinces such as Buenos Aires or Misiones. In the case of Salta, they worked as laborers on farms and when they raised money they bought a piece of land and began to grow their food. This is how they dedicated themselves to floriculture. Among them we can name Shoji Sato, Zenshiro Heshiki (in Jujuy), Tadao Hisamatsu and Shigeki Maruyama, along with his wife Chiyo, who dedicated themselves to horticulture/floriculture and worked on farms in the province.

There were very few who were in a different field, as was the case of Hidehiko Iwai, who was a hairdresser; or Zenshiro Heshiki, who dedicated himself to carpentry in Salta. In addition to that, it should be noted that some not only carried out one activity, but also experimented and changed jobs, depending on economic needs or what they could get. It is observed that for a certain period of time they were gardeners or worked on farms, then, with the rise of coffee shops, they changed jobs to waiters or set up dry cleaners. For example, you can name Saburo Onaga, who worked on a farm for a while and then was a waiter in a cafe, or Eisuke Iwashita, who started working in a meat processing plant, was a gardener in Tucumán and, finally, ended up as a waiter and street vendor. (he sold picolé or ice cream, according to the interviews).

By the time the migrant had already completely settled in the province, they will begin to meet, first in cafes and then they will begin to look for their own containment spaces. In this migratory process, Japanese associations will emerge, in charge of agglomerating migrants in countries unknown and different to them. This is how the Japanese Association of Salta emerged in 1951, located in the macrocenter of the City of Salta, in the province of Salta.

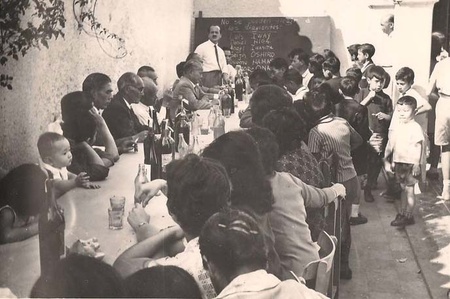

The idea of the Association arose in the meetings of the countrymen in some migrant cafes or in the houses of their compatriots, where they carried out some recreational activities, such as playing cards, singing karaoke, among others. Another activity was to go on a picnic every first of May to enjoy the outdoors and food. In this process, the need arose to have a place to meet and share among their peers. The main objective of this institution was and continues to be:

“Strengthen ties between associates for the progress and prosperity of the institution. The establishment will not take part in any political, religious or social movement. In addition to linking with other associations of the same nature to exchange knowledge about Japanese civilization, customs, arts, music, etc.” (Association minute book, regulations section).

It began as a space where they shared practices, remembered old times (some came from the same towns), transmitted their customs and functioned as a place of containment and recreation for the Japanese and their families for many years. The associations, apart from being spaces for the recreation of identity, in this case ethnic and cultural, were also spaces where the meanings of identities are negotiated and articulated in a migratory context and mutual aid between migrants (Montesinos and Rodrigo, 2011).

The Japanese Association and Nikkei Center of Salta played an important role within the Japanese families of Salta, being a place of meeting, friendship and refuge for migrants, as well as a space for descendants to share, learn and socialize. Currently, although it continues to function, it has lost its central role within the community. The low participation of the descendants led the institution to open its doors so that young people or adults who do not have Japanese ancestry can share with their peers the taste for Japanese culture and Japan, as a way for the association not to disappear.

Analyzing all of the above, it can be said that in Salta there were certain processes that occurred at the national level and that were repeated in the province, such as the reasons for migration, the jobs they dedicated themselves to, places of origin and the characteristics of the migration to Argentina (indirect and spontaneous). Likewise, the non-formation of Japanese neighborhoods, as in other countries such as Brazil or Peru, where migration was of a much greater nature. This is also because circumstances in Argentina did not force Japanese people to gather in neighborhoods due to discrimination, as happened in countries like the United States or Brazil.

On the other hand, there are processes that make a difference with respect to other provinces, such as the non-formation of Japanese agricultural colonies, linked to the low flow of migrants that arrived in Salta, compared to large cities like Buenos Aires. Furthermore, the phenomenon of dating agencies for young singles did not occur, as mentioned before. Finally, the low number of migrants who arrived after the Second World War, compared to other provinces where migration never had a break and continued to maintain a high number of Japanese entry. All these characteristics caused the Salta Japanese community to be small and disperse over the years, leaving the association as a memory of those days.

Grades:

1. The name and owners of the latter could only be known thanks to the book of the Japanese Immigrant in Argentina , since when interviewing the descendants they do not remember that this cafe ever existed.

2. 呼び寄せ( yobiyose ): migration by call. (呼[よ]び: yobi which means to call, require; and 寄[よ]せる: yoseru which means to approach, gather, collaborate).

Bibliography

Federation of Nikkei Associations in Argentina (FANA) (2004). History of the Japanese Immigrant in Argentina, Volume I. Prewar Period. Research and Writing Committee on the History of the Japanese Immigrant in Argentina. Bs. As.

Federation of Nikkei Associations in Argentina (FANA) (2005). History of the Japanese Immigrant in Argentina. Volume II. Postwar period. Research and writing committee on the History of the Japanese immigrant in Argentina. Bs. As.

Gómez, S. & Onaha, C. (2008). “Voluntary Associations and ethnic identity of Japanese immigrants and their descendants in Argentina” , Migraciones Magazine, number 23. Madrid.

Ichikawa, S. (2004). The historical and current evolution of Okinawa as seen by Oshiro Tatsuhiro. XI International Congress of ALADAA.

Labarthe, M. G. (1982). “The Japanese community in Salta and Jujuy: an anthropological study on its integration into the environment.” (Bachelor's thesis of the Anthropology degree). Faculty of Humanities, National University of Salta, Argentina.

Laumonier, I.J. (2004). “Cafes, dry cleaners and tango . ” In When the East Comes to America. Contributions of Chinese, Japanese and Korean immigrants, pp. 161-178. Inter-American Development Bank, Washington DC.

Matsuyama, L. S. (2010). “Nikkei experiences of Cultural Frontier: Argentine and Peruvian immigrants of Japanese descent in Okinawa, Japan”, in Naguare, no. 24. ISSN 0120-3045, pp. 157 - 193, National University of Colombia, Bogotá.

Montesinos, EG & Rodrigo, MA (2001). “Immigrant associationism and renegotiation of cultural identifications in politics and society”, Vol. 48, No. 1: 9-25.

Onaha, C. (2002). “Japanese immigrants and their descendants in the province of Buenos Aires” in Where are the immigrants? Sociocultural mapping of immigrant groups and their descendants in the province of Buenos Aires . Editions al Margen, La Plata.

Onaha, C. (2011). History of Japanese migration in Argentina. Diasporization and transnationalism.

© 2022 Sofia Garzon