Life After Internment in Edmonton

“At age 14, I had no ambitions but once I left the internment camp, I had the good fortune to live in the Misericordia Hospital, as did my sister. We were relief elevator operators for which the nuns provided us with room and board for working on weekends. We were enrolled into Garneau high school, which was across High Level Bridge, a 2 km walk or 10 minutes, by streetcar. Another classmate and I walked daily across the bridge except in winter when in a blizzard the temperature could reach 20 to 30 below; that was cold even at a brisk walk. The education taught by the nun teachers at Notre Dame High school was superior.

“My sister and I went directly into a ‘big time’ high school directly from a small back country high school. Within three months, both of us were near the top of our respective classes. There was no doubt about the high quality of teaching we received at Notre Dame. They had at first some of New Denver internees build a kindergarten but the mothers said that they also needed a high school. The BC politicians said that they would fund elementary but not high school. So, the nuns went back to Quebec and after a meeting they returned and said that they would build a high school and there would be no religious studies at the school. There were only two families who were Catholic. But one sister in the Nishikaze family was a devout Catholic.

“We went to Edmonton from New Denver in 1946. The BCSC continued to prevent JCs from returning to the west coast until 1949. Papa had hoped to return to Prince Rupert. Edmonton was a great choice - it was the capital, had over 100,000 people and a good university with a first class faculty of medicine - the only one in the west. Two years after coming to Edmonton, I was accepted into the University of Alberta (UA) pre-med class, one of the first JCs admitted into medicine after the war. Once I was in, the UA was able to get me training in the US at one of the best training centres for plastic surgery. At the time, I could not train in Canada: it was a closed shop too out east in Canada. I was in medicine from 1950-1959, then in the US from 1960 until 1962.

Reflecting on Loss

“The economic loss and the future of the JCs was uncertain. As a west coast community, we were just starting to prosper. The internment was a tragedy and was not a national security problem as the RCMP and military said. But people were swayed to believe that there were enemy aliens and spies amongst the JCs. No JCs were ever charged as a spy or saboteur. In August 1944, PM Mackenzie King told the House of Commons that there had not been any National security need to remove the JCs from the coast, but that he wanted them dispersed anyway: A real oxymoron.

“Papa and George were doing so well that he bought three rental houses. They were very successful. The food was so good and very popular. When WWll started, the hotel and restaurant became even busier.

“My father and George intended to transfer the business to Shoiji Shimizu, my half-brother who was Canadian born and over 18. However, the BC Security Commission decided not to honour his ownership and confiscated the property, which was valued at over $80,000. They received $10,000. I am not sure what happened to the Prince Rupert rental houses.

“Papa never recovered although he did start an apartment and rental houses in Edmonton after internment. However, due to poor medical advice and neglect, he gradually became blind by the 1960s. He lived to be 95 and died in 1982. He and Kimiko did travel while he was blind - to Japan, the Holy Land, Egypt, and several times to Toronto and Montreal.

“George and family went to Montreal. George worked at the Ritz Carlton in Montreal. Like I said, he was a superior cook. After his wife died, he came to Edmonton to stay with the Shimizus for about six months during the late 1970s and returned to Japan where he died soon afterwards.

“I don’t feel that there is much you can do about the past but just the other day the NAJC Committee has negotiated another $100 million from the BC government for the internment survivors. Unfortunately, this does not include me because I have too much money. Besides, they are aware that as the chairman of the JC Redress Foundation, in 2002 the NAJC received $3 million and $350,000 each to foundations for education, community, and sports, which I hope has been wisely used.

“You should know that I did not receive any support for my paintings. I did receive lots of private help from friends though but none from the NAJC or local JC cultural groups. The NAJC needs more people with vision that goes beyond local interests.”

80 Years After Internment: A Yonsei Perspective

Commenting on the importance of art and memory, Marsh says:

“Art serves as a way to express emotions that are sometimes more impactful left unsaid. While we often try to create a single narrative around the internment experience, Dr. Henry Shimizu’s unique perspective taught me that all memories of internment are equally valid and deserve to be cherished. Henry’s choice to present his memories of internment through painting has helped make this history more accessible to an audience who would not have been reached otherwise. Henry’s artworks frequently portray complex and often conflicting themes and emotions. I have an increased appreciation for art's ability to navigate complexity.”

She points out that as an American, she sees some differences in how the internment is remembered in Canada versus in the US:

“There seem to be two historical differences that shape how internment is remembered and spoken about in Canadian versus the US. The first was the unconsented sale of Japanese Canadian property during internment. The second was the prevention of Japanese Canadians from returning to their homes on the west coast until 1949, four years after the war had ended. This combined loss of property/wealth and locational community after the internment years has irrevocably shaped the concentration of Japanese Canadians across the country. We see this difference most tangibly with the size and scale of ‘Japantowns’ in the US versus their counterparts in Canada.

“In my own experience talking with my JA relatives and members of the JC community, it appears that Japanese Canadians on the west coast talk more openly about internment than their JA counterparts. I must stress that this is anecdotal and is a topic that I want to further research. I would further like to add that there were huge differences in the JC community’s experience and therefore remembrance of internment based on their location. For example, the JC internment experience ranged from manual labour camps, sugar beet farms, to New Denver’s TB sanitorium.”

“Looking into the future, I hope that visitors make connections to issues affecting their own communities,” pointing out the intersectionalities with new generations of immigrants. “I see parallels with other communities in Canada that have faced racial injustice and displacement - the Chinese Head Tax, the Komagata Maru, Residential Schools, and so many more. A common saying around Japanese internment in Canada has been ‘Shikata ga nai’- it can't be helped. I think as we look at current injustices, we should challenge this concept.”

As a commentary about the internment experience 80 years later, Marsh says:

“This exhibition challenges the concept of a collective memory of JC internment. By using the direct quote of Issei, Nisei, and Sansei, the visitor is faced with the complex relationship these generations have with their community, country, and home. Something that will hopefully become striking to the visitor is that even within the same family and camp, the memories and experiences of internment can be vastly different.

“This year also marks an important memorial year for the Japanese Canadian community. In fact, on May 21, B.C. Premier John Horgan committed a $100-million endowment to address the lasting effects of the internment of Japanese Canadians in the province during the Second World War - what some are calling the second wave of Redress. This particularly connects with this exhibition, because Henry Shimizu played a crucial role in advocating for the Japanese Canadian community, including chairing the Japanese Canadian Redress Foundation from 1989 to 2001 and later receiving several awards, including the National Association of Japanese Canadians’ National Award (1999) and the Order of Canada (2004). With this memorial year, I believe it’s important more than ever to record the stories of survivors of internment.”

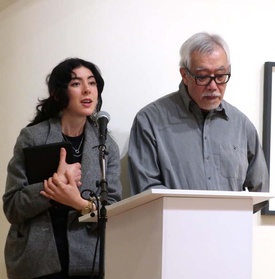

Although there are no confirmed plans to display the paintings elsewhere, both Dr. Shimizu and Samantha hope to take the exhibition to other centres across the country.

Marsh points out important learning opportunities for her throughout the research and outreach for this exhibition.

“I’ve had the pleasure to learn about and connect with numerous JC community organisers who generously shared their time, teachings, and guidance with me, particularly Bryce Kanbara who was my mentor throughout this exhibition process. His support and advice guided me through the curatorial process, and he has inspired and instilled confidence in me to pursue future curatorial work. I hope to continue to learn with and from Bryce and the numerous individuals and organisations I had the privilege of meeting.”

As a young Nikkei, Samantha recognizes that the arts and culture are powerful tools for community building.

“Art has the ability to bridge communities, and I have seen this exemplified with the Powell Street Festival Society. Now in its 46th year, the Powell Street Festival is the longest arts and culture festival in Vancouver and the largest Japanese Canadian festival in the country. This grass-roots annual festival was founded as a way to bring together the displaced JC community in the seventies, and it takes place in the Powell Street area, or as early JC immigrants called it, the Paueru Gai.

“The Festival has since developed into an organisation which offers year-round programs that collaborate with local organisations, artists, and communities to celebrate Japanese Canadian arts and culture for social good. This included establishing meaningful connections with other displaced communities, minorities, and under-advocated groups to foster allyship, resource sharing, and community supports such as the DTES Community Care Programs.

“Thus, I have seen first-hand how arts can be used by the JC community as a medium for establishing itself as an ally to numerous under-represented communities and groups facing hardships. Moving forward, I believe the JC community can further strengthen its connections with other communities through artistic and cultural collaborations and exchanges.”

*Learn more about Isshoni: Dr. Henry Shimizu’s Paintings of New Denver Internment at the University of Victoria’s Legacy Gallery, please check out this brochure.

© 2022 Norm Masaji Ibuki