The life, hardships and resilience of the Tani family

As evening fell on July 18, 1926, a Dodge touring car packed with the nine-member Tani family came barreling down the road to Kahului. Mitsuzo, the patriarch, sat in the front passenger seat with his three-year-old daughter Yachiyo tucked beside him. Seven other family members filled the back seat, including Fusae, 11. The family was returning home from a Sunday outing to Pā‘ia Camp, where the children played while the men swapped stories and downed cups of sake. A family friend took the wheel on the drive home. As the car rounded a bend near Kanaha Camp, it veered suddenly and toppled over, pinning everyone. Mitsuzo, 54, was killed instantly. Daughters Yachiyo and Fusae died shortly after being rushed to Malulani Hospital. The horrific crash landed on the front page of Maui News and forever upended the fortunes of the Tani family.

Mother Sumi, 35, had no time to mourn the untimely deaths of her husband and daughters. She suddenly became both a widow and the sole provider for five children, the youngest just 18 months old. She didn’t have a lot of options, given her fourth-grade education and limited English language skills.

But over the next decades, through sheer grit, self-invention and perseverance, Sumi pieced together a life that kept her shattered family together. She found the will to survive. “My mother always said gambare or endure your hardship,” says Sally Shinobu, Sumi’s youngest child. “That’s what my name, Shinobu, means. And that’s what her whole life was.”

Sumi Tani was my grandmother. Her only son, James, was my father.

The road to Makawao stretches up the broad slopes of Haleakalā. My aunt, Sally Shinobu Kuba, lives in a cottage below the mountain’s imposing summit. She’s petite, with cropped gray hair and keen, crinkled eyes. At 97, she’s also the accident’s only remaining survivor. Settling herself into a wicker chair, she begins to recount our family’s story.

As a girl growing up in Yanai, Japan, Sumi Matsumoto was known as a skilled kimono maker. The eldest of four, she ran the household when her father, a caterer, and her mother, a midwife, were called away for work.

By age 20, the slender, reserved young woman had refused several proposals of marriage. But she’d also heard alluring tales of a place called Hawai‘i, so when her father handed her the photo of a young ex-priest from Yanai, who proposed marriage in Hawai‘i, she studied it with interest. He wore a Western suit with his hair parted to the side, and looked distinguished. She knew that if she turned down his proposal, she’d become an intolerable burden on her parents, but if she said yes, she’d have a chance at a promising new life. She said yes.

On Aug. 18, 1911, a steamship carrying Sumi and other shashin hanayome, or picture brides, docked at the port of Honolulu. They were among the initial wave of picture brides to arrive in Hawai‘i (more than 20,000 picture brides came to the islands between 1908-1924). Sumi, who’d been gripped by sea sickness throughout the voyage, walked unsteadily along the pier, clutching her bundle of possessions. The 4 foot, 10-inch bride-to-be wore a crisp cotton kimono with her hair swept into a pompadour.

After exiting the health screening, she looked nervously at the line of men who were waiting outside. One stepped forward, holding up her picture and calling her name. But it wasn’t the young man from the photo. Instead, before her stood a weather-beaten and balding man twice her age – this was Mitsuzo. The couple married in a group ceremony outside the immigration station, then boarded a boat for Napo‘opo‘o. Sumi cried for days.

Despite their initial rocky start, Mitsuzo and Sumi Tani led a bountiful life. Mitsuzo was the second of three sons born to a priestly family in Yanai, Yamaguchi-ken, in southwestern Honshu. At 26, he abandoned the Buddhist priesthood to work on Hawai‘i’s sugarcane fields, driven perhaps by Japan’s declining economy and by rumors of the vast fortunes to be made in this faraway “paradaisu.” He arrived by steamship in 1898, the year Hawai‘i was annexed by the U.S.

By the time of his arrival, the sugar industry had transformed Hawai‘i. Sugar exports fueled the economy and, in 1893, western sugar planters engineered the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Plantations initially brought in field laborers from China but soon turned to Japan and other nations for migrant workers. From 1885 to 1924, more than 200,000 Japanese immigrated to the islands. Roughly half chose to stay after their contracts ended.

Mitsuzo was one of them. He arranged for Sumi to join him as his wife in Napo‘opo‘o, Hawai‘i, where he ran a horse-drawn taxi and blacksmith operation. A restless entrepreneur, Mitsuzo seized an offer to take over a blacksmith’s shop on Maui. He moved his family, which then included daughters Doris Masayo and Fusae, to the bustling shipping hub of Kahului. There, Sumi gave birth to Yachiyo, Molly Kaoru, James Futoshi, Elizabeth Misaki, and Sally Shinobu. Mitsuzo, who spoke fluent Hawaiian, struck a deal with the native fishermen at Kahului Harbor: He’d fix their boats in exchange for fresh fish to feed his growing brood. The Tanis ate very well.

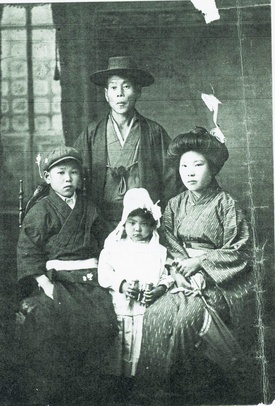

A studio portrait taken two years before the accident depicts a large, well-attired family. Sumi wears a formal kimono with a delicate bamboo design and holds year-old Yachiyo in her lap. The older girls are outfitted in ruffled dresses, tights and ankle-strap flats while James grins impishly and shows off his wristwatch. They were a family on the rise.

“In Kahului, because of my father’s educational background and his immense knowledge of kanji, he became a town leader,” said Sally, recalling the stories her mother would tell. “If people got letters from Japan with characters they couldn’t read, they’d go to my father—the village blacksmith!”

When Japanese silent films played on Vineyard St., Mitsuzo sometimes took the role of benshi, the narrator who explains the action and voices each character. “Imagine acting the role of the lady, the man, the child. Not everybody can do that but he did,” laughed Sally. “My father was a real ham, so whenever he was the benshi, the movie was exceptionally good.”

Mitsuzo’s close friends were Katsuhiro Miho, a Japanese-language school principal, and Tetsuichi Kaneshige, the owner of a watch and jewelry shop in Kahului (the store closed in 2004).

In the mid-1920s, automobiles began overtaking horses as the primary mode of transportation. Recognizing the threat to his blacksmith’s trade, Mitsuzo started a side business that converted flat-bed trucks into semi-enclosed “banana wagons.” Like many immigrants, he was vigilant to niche business opportunities and adept at retooling his skills to a changing market. “He planned to bring in a lot of Ford motor cars and have a slew of gas stations all over Maui,” Sally tells me. “But then the accident happened.”

An inquest into the accident faulted the car’s driver for operating recklessly without a license, but that did nothing to ease the family’s profound grief. In the accident’s aftermath, Sumi found herself shunned by other Japanese in Kahului. “They avoided her because they were afraid she’d ask for their help,” Sally explains. “Because everyone was struggling to make ends meet.”

The family moved into a shed on the slopes of ‘Īao Valley, which isolated Sumi even more. There were no family members or relatives who could help her or provide comfort. Instead, Sumi suffered in silence and in exile. Each day, she prayed before the butsudan but prayers and tears did not feed her family. So she worked.

Sumi began apprenticing at M.F. Amboy Tailor Shop on Market St. in Wailuku, where she learned to operate a treadle Singer sewing machine. She eventually earned 60 cents for a pair of men’s khaki trousers and $1.20 for gabardine pants. The work was tiring but preferable to toiling in the blazing hot sugarcane fields, where a woman might get $1.30 for a full day’s labor. Sumi worked 10-15 hours a day, six days a week, leaving her youngest in the care of a neighbor.

By 1930, several years after the accident, Wailuku was surrounded by 30,000 acres of sugarcane while its streets abounded with businesses catering to the plantations. Sumi was earning enough as a seamstress to move the family into a one-bedroom house behind ‘Īao Theater, in the heart of town. The children walked to nearby Wailuku Elementary and Wailuku Intermediate, and took Japanese language classes after school. Each Sunday the family worshiped at Wailuku Jodo Mission, where Sumi helped prepare food for festivities such as Obon. Sally loved her weekly lessons in mai Japanese classical dance, held above Yokouchi Bakery amid the tantalizing aroma of fresh-baked biscuits and bread.

* This article was originally published in The Hawaii Herald on July 15, 2022.

© 2022 Carlyn Leinani Tani