In Part 1 of Chapter 8 about the growth of Japanese Barbershop businesses, I wrote about the Japanese Barbershop Committee and the increase of the haircut price. In this part, I would like to share some articles about the Seattle general strike and the Nisei who strove to start their own barbershop businesses around 1939.

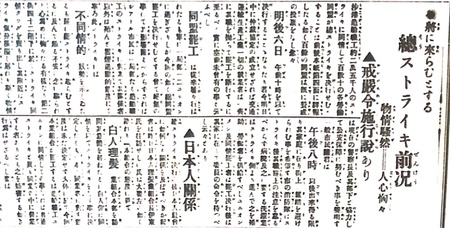

Seattle General Strike “Relation with the Japanese” (From the Feb. 4, 1919 issue)

In February 1919, in sympathy with the strike of approximately 25,000 shipyard workers in Seattle, more than 100 labor federations spread across Seattle went on general strike. At the time, to figure out how it would affect the Japanese community, a reporter from “The North American Times” visited the head of the Japanese Barbershop Committee Ito and conducted an interview. Here is what Ito said:

“Upon visiting the headquarters of the Caucasian Barbershop Committee and inquiring about their intention, we learned that they have decided to go on strike in sympathy with Caucasian workers. They have yet to decide what message to send to Japanese peers... They expect the Japanese to go along with the strike if and when the Caucasian Committee decides to also ask for their sympathy. Thus the Japanese Committee will have to make their own decision based on what the Caucasian Committee decides. Once the general strike begins, however, it is clear that even without a chance to negotiate shops will have fewer customers, and Japanese barbers will eventually have to close their shops if all the infrastructure including electricity and water gets halted. It is such a foolish turn of events and a pity on the otherwise growing economy and its productivity.”

The Japanese Barbershop Committee had no choice but to follow the Caucasian Committee and closed their businesses. They reopened on February 11 after the strike was over. There was an ad to inform readers of the reopening in the February 10 issue.

WE AGREE TO THE SAME BUSINESS HOURS

“Hokubei Nihonjin-kai Conference” (From the July 31, 1919 issue)

“The Japanese Barbershop Committee has been working closely with the Caucasian (peer) Committee and is in agreement with what they did. This time, the Japanese committee is being asked to agree to operate on the same hours that the Caucasian peers have started to adopt. Upon discussion, the committee has accepted the request of the times, and to show their willingness to cooperate as peers, announced the following...

On the last day of July 1919, by the Seattle Japanese Barbershop Committee:

‘We will operate from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m. and from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. on Saturdays only. Effective as of August 4.’"

Japanese barbershops had operated from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. every day until then. From the Caucasian perspective, the Japanese were working too much and were becoming a nuisance to their businesses. This was one trigger of the anti-Japan movement. To prevent it, the Japanese committee accepted the request from the Caucasian side and agreed to shorten their business hours.

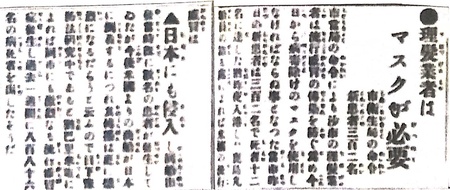

SPREAD OF SPANISH FLU

“Barbers Must Wear Masks” (From the Oct. 24, 1918 issue)

“Under the order of the city authorities, starting today all barbers are required to wear masks for disease avoidance to prevent the spread of the flu. There were 302 newly reported patients in Seattle yesterday, and 12 people have died so far. According to the information from Kashima-maru which arrived in port last night, the flu has entered Japan, and a few patients had been reported at the time of the ship’s departure... A telegraph from Paris has informed us of the raging flu in the city with 886 disease-related deaths reported in the past week.”

We can read a report on what life was like in Seattle at the time in the November 12, 1918 issue.

“We have been under the special order of the Washington State Department of Health since October 2 to have our faces covered at all times, but on November 11, the order was lifted, which was great news to us. As of yesterday, there have been a total of 485 deaths since October 2. The number of patients had reached a little over 10,000 by October 9. During this period, theaters, movie theaters, temples, schools, and many other places were all shut down. Retail stores opened from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., and all businesses except for food suppliers were closed on Saturdays.”

As a way to prevent the spread of infection, people had to live under such strict restrictions 100 years ago too. Barbers were required to shorten business hours and wear masks during this period.

In the November 16, 1918 issue, I found an article reporting on the strong recommendation for barbers to continue wearing masks to prevent another spread even after the restriction order was lifted.

NISEI SUCCESSORS

Beginning in 1930, more and more Nikkei returned to Japan due to the economic depression and the worsening of U.S.- Japan relations. The number of barbers decreased as well (see graph). On the other hand, some Nisei in the remaining families were making their own moves to take over their parents’ barbershop businesses. Let me introduce some articles about them.

“What a Delight: a Nisei Barber’s Daughter” (From the Jan. 13, 1939 issue)

“(1) There is Momoichi, who is the second son of Jitsuzo Nakata who runs a barbershop on Bainbridge Island. He graduated from Bainbridge High School last year. With the determination to take over his father’s business and explore the real world, he enrolled this early spring in Moler Barber College (MBC) which is located at 104 First Avenue (probably Seattle). He is looking forward to his day of graduation and using his hair clippers at work.

(2) There is another son by the name of Sumio, whose father — Kyusuke Tsubakihara — runs his barbershop business on Main Street. He, too, with a fresh mind decided to make a living with a pair of hair clippers — a tool with which his father raised his children. He is currently attending MBC as well.

(3) Michie (age 19) is the daughter of Masadome Shimokon, who owns Union Hotel on Washington Street. Having a realistic view on life, which is a rather rare trait of a young female, she thought that even as a Nisei, getting vocational training would come in handy in the future within the Japanese community. She studied at MBC and recently graduated, which is great news. She says that she wants to either work at a barbershop soon or open her own shop. A Nisei daughter becoming a barber – what a delight.

(4) Frank, who is the son of farmer Gokichi Tanikawa in Kent, is also a Nisei who plans to become a barber and went to MBC. He has already received his diploma and is currently preparing to open his shop.”

“Hokubei Shunjyu—The Nisei Barbers” by Ichiro Hanazono (From the Mar. 9, 1939 issue)

President of Hokubei Jijisha (North American Time Co.) Sumiyoshi Arima (under the pseudonym Ichiro Hanazono) commented in the column “Hokubei Shunjyu” (North American Spring and Autumn) about Nisei barbers.

“The barbershop business has played an important role in the development of our community. We could say that these days, though, its presence owes much to a mere habit from the past with no new apprentices or people opening their shops. This doesn’t mean, however, that the future of the business is marginal. I believe that it has enough potential to grow, if one can start with new equipment and new skills. It is a business suited to the Japanese. The Nisei’s jobs will not forever be limited to driving trucks. I had the most fun reading the story about the emergence of Nisei barbers among the recent articles in ‘The North American Times.’”

We should remember that there were some Nisei who decided to take over the barbershops that the Issei had built up with so much hard work.

This is how the Japanese barbershop business developed in Seattle; it took advantage of some cultural features unique to the Japanese. We can see from the articles of “The North American Times” that the Japanese Barbershop Committee, led by Chuzaburo Ito, was the one that supported its development, with dedication and effort despite persistent discrimination from their Caucasian peers and the anti-Japanese movement.

In the next part, I will introduce some articles about the Japanese hotel business, which also thrived in Seattle.

References:

Hokubei Nenkan (North American Yearbook), Hokubei Jijisha, 1913.

Kojiro Takeuchi, History of Japanese Immigrants in the Northwestern United States, Taihoku Nippo-sha, 1929.

Kazuo Ito, Hokubei Hyakunen Zakura (100-Year Cherry Blossoms in North America), Nichibou Shuppan, 1969.

*The English version of this series is a collaboration between Discover Nikkei and The North American Post, Seattle’s bilingual community newspaper. This article was originally publishd on June 11, 2022 in The North American Post and is expanded for Discover Nikkei.

© 2022 Ikuo Shinmasu