Toshia Mori was not the only performer from the Ichioka clan, nor the only family member to win renown. First, sister Mia was able to build her own film career outside Toshia’s shadow. Mizuye “Mia” Ichioka was born in Japan on Jan 28, 1916, and arrived in the United States as a small child. In the early 1930s, Mia studied at Los Angeles’s Poly High School, graduating in 1933.

Mia’s first film role (nilled as Media Ichioka) came when she appeared together with sister Toshiye in the silent film Streets of Shanghai (1927), playing the Chinese girl F'aien Shi. Mia may also have appeared in Mr. Wu. After returning from a year in Japan, she sought extra work. According to one source, she and her younger sister Sue (Shizuye) Ichioka, two years her junior, were extras in the 1933 Warner Bothers film Footlight Parade, while Mia appeared in the 1934 film Marie Galante.

Mia’s first identifiable role was as GeeGee in the 1934 film Wonder Bar, starring Al Jolson and Kay Francis. (The film, adapted from a Broadway musical and set in a Paris nightclub, is today known chiefly for a comic queer scene—a man asks a dancing couple if he can cut in and the female partner agrees, but he dances off with the male partner, much to the woman’s consternation, while Al Jolson quips, “Boys will be boys!”).

Mia received her greatest public notice for her performance in the 1936 film Love Before Breakfast, as Yuki, the maid to Kay (Carole Lombard). Although forced to use a broad Japanese accent and spout retrograde ideas, Mia showed fine comic timing in her dialogue with Lombard.

In multiple scenes, Yuki reads Kay’s fortune, using tea leaves. When Kay asks what they say, she responds, “They say you meet big strong dark man, Miss Kay. They say he give you black eye, then marry you.” She further explains, “When Japanese girl love Japanese man, she go to him and she say, ‘I love you...’ Then, everything right away fine.” Kay complains that the Japanese girl then gets shoved around, and Yuki retorts, “Japanese girls liking to be shoved around.”

Mia’s performance was singled out as “notable” in the Hollywood Reporter. Writing in the Chicago Tribune, critic Mae Tinee referred to Mia Ichioka as “a remarkably pretty Japanese girl with personality and a charming voice.”

Mia’s next role was as “Hua Mei,” opposite actor Tetsu Komai, in the 1937 film West of Shanghai, which starred Boris Karloff in yellowface as a Chinese warlord who abducts a Western businessman. She appeared in bit parts in two other movies, as a courtier in the 1938 film The Adventures of Marco Polo, starring Gary Cooper, and as a Japanese telephone operator in the 1939 film “Rio.” (she also claimed that she appeared in the 1940 film Forty Little Mothers.)

During this time, Mia and her sister Sue led personal lives that were uncommonly racy by the standards of teenage Nisei women of the period. In April 1934, newspapers reported that the sisters had left the Ichioka home in an automobile after a family quarrel, taking all their clothes and some money. Their father reported them to the local sheriff’s office as runaways, and police began a search. A month later Sue filed notice of her intent to marry Ken Ung, a Chinese-American college student and basketball player. Sue gave her age as 20, though she was actually 16.

While the marriage to Ung seems not to have taken place, interviewer Richard Potashin noted that in 1934 Sue married a man named Frank Yoshida, whom she then divorced in 1937. “[D]uring that time she had apparently some other relationships, one with a Chinese man who was referred to as Sam Tong or Frank Loi, there was all these different aliases.”

Sue gave birth to two children during this period. In an oral history interview, Celeste Teodor, Sue’s daughter, stated, “I was born June 24, 1936, at the Queen of Angels Hospital in Los Angeles…The only reason why I know this information is through my birth certificate. And at that time my mother was not living with her husband [whose] address was unknown. That's all it says...She was eighteen years old and I was the second [of two children], one baby had already died before I was born.”

Teodor added that on her birth certificate, her mother was listed as Shizue Yoshida, and Frank Loi was listed as the father. The baby who would be named Celeste Loi was immediately placed in an orphanage, and she did not learn who her birth mother was until she was ten years old.

Meanwhile, at some point Mia had also gotten married, to Tadashi Yoshizaki. In February 1935, aged 19, Mia gave birth to a son, who was originally named Tod Yoshizaki. Soon after the baby’s birth, Mia and Tadashi Yoshizaki petitioned for divorce. Mia moved to a residence next to her father’s house, where she lived with her son and her mentally handicapped sister Irene Futaba Ichioka. In the 1940 census, Mia Yoshizaki described her job as a check girl in a nightclub.

Sometime in the 1930s, Mia became romantically involved with actor and businessman Otto Yamaoka (himself the subject of a Discover Nikkei article). Yamaoka may have been the biological father of Mia’s son. Whatever the case, in 1942, when Otto and his family members were confined under Executive Order 9066 at Santa Anita Assembly Center and Heart Mountain, Mia and Tod joined them and shared their family identification number. Mia stayed with Otto for the rest of his life, and at some point she started using the professional name Mia Yamaoka, although it is unclear whether she and Otto were legally married. Otto adopted Mia’s son, who took the name Joseph Yamaoka.

In August 1943, Mia and Otto Yamaoka moved to New York, where Otto had family members. Mia and Otto opened the firm of Yamaoka & Co. Importers and Exporters, which was most notable for distributing Japanese films to the US market. In 1955, they distributed the Japanese film Hiroshima, a narrative about the atomic bombing of Japan, for which Mia created the English subtitles and narration.

They announced their intention to join with a Japanese studio to produce a color film in Japan based on the life of Tesshu Yamaoka, Otto’s grandfather, a celebrated samurai in the 19th century, and to produce a film on the life of Kokichi Mikimoto, the “cultured pearl” king, but neither project seems to have been realized.

Otto died in 1967. In later life, Mia Yamaoka worked as an analyst for the Value Line Merger Evaluation Service. She also copyrighted the script for a two-part commercial: “You don’t have to be having fun to enjoy our beer.” She died in New York on December 29, 1998.

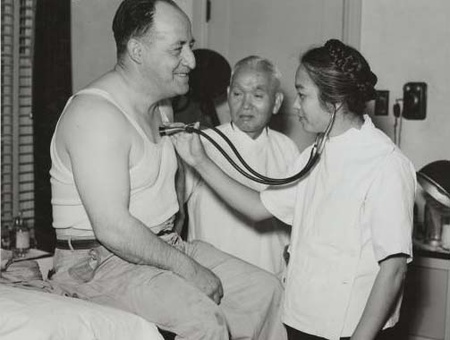

Beyond Toshia Mori and Mia Yamamoto, another notable woman connected to the Ichioka clan was Dr. Tsutayo Ichioka. Born Tsutayo Nakao in Hawaii in 1905, she graduated from nursing school. While working as a nurse at the Japanese Hospital in Boyle Heights, she met Dr. Toshio Ichioka. They married in July 1930. (Because Toshio Ichioka was an “immigrant ineligible to citizenship,” Tsutayo was stripped of her American citizenship under the Cable Act after marrying him, and had to petition for naturalization the following year).

Toshio inspired in Tsutayo an interest in studying medicine. There was some irony here: Toshio Ichioka succeeded to a family of doctors (“when they all get together,” Toshia Mori later cracked, “it sounds like a medical convention”) but none of his daughters studied medicine. However, when his young wife decided that she, too, wanted to become a physician, he agreed to fund her medical studies.

In 1935 Tsutayo became the first Japanese American woman in history to be admitted to USC’s School of Medicine. Her sister Satsuki Nakao, ten years younger, enrolled at USC pharmacy school, where she received her degree in 1940). Tsutayo graduated medical school in 1938, then went East to complete her residency in obstetrics and gynecology (according to reports from different sources, she went through internship and residency at University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in Pittsburgh, in New York, and in Vienna). Whatever the case, in mid-1941 she returned to Los Angeles and went into practice. Her sister Satsuki worked at the pharmacist at the Ichioka clinic.

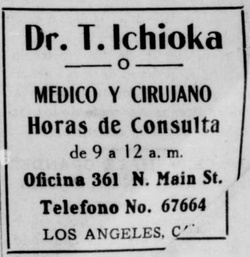

In February 1942, La Opinión ran a front–page story on Tsutayo Ichioka. It described her as the “wife of Dr. Toshio Ichioka, well known in our community,” who “following a voyage to the east of the country, where she studied and practiced in the most famous hospitals” was opening a new office. (The Drs. Ichioka continued to advertise regularly in the pages of La Opinión until they were forced to close their office in May).

In 1942, the Drs. Ichiokas were removed from Los Angeles under Executive Order 9066. They sealed three of their four houses and left the fourth with a caretaker. They were confined, together with Satsuki Nakao, at Pinedale and then Gila River. While in camp, by her own reckoning, Dr. Tsutayo Ichioka saw an average of 150 patients a day, and she delivered numerous babies.

In October 1943, the family group left camp and resettled in in Des Moines, Iowa. Tsutayo was hired as house physician at Mercy Hospital. In 1945, they returned to Los Angeles and reopened the clinic in Boyle Heights, by now a largely Hispanic neighborhood.

Dr. Toshio Ichioka seems to have ceased practicing medicine in the next years. Instead he became an investment broker with the Taiyo Securities company, as well as a pioneer in Japan’s fledgling television industry, serving as a director of the Japan Television Co. In 1958, he attracted publicity by sending a color television set to Japanese prime minister Nobusuke Kichi. Dr. Tsutayo Ichioka continued to practice medicine until her retirement in 1975.

In later years, she and her sister set up the Tsutayo Ichioka and Satsuki Nakao Scholarship at USC, a charitable trust designated to provide support for medical and pharmacy students who demonstrated financial need and interest in Japanese heritage. Dr. Tsutayo Ichioka died on November 26, 1996.

It is unclear what relations Toshio and Tsutayo Ichioka had with Toshio’s daughters. According to the 1930 census, all four sisters lived together with their widowed father. Presumably it was hard on the teenagers when Dr. Ichioka married a much younger woman soon after their mother’s passing. They did seemingly keep some connection. In 1933, Toshia fell ill and spent two weeks under her father’s care. While Mia and Sue were teenage runaways, as noted, Mia and her sister Irene lived next door to their father during the late 1930s.

The estrangement grew with time. The family members were in separate camps: Both parents went to Gila River, Irene was in Manzanar, and Mia in Heart Mountain. When Dr. Toshio Ichioka died in June 1960, his newspaper obituaries were silent on his well-known daughters, who later claimed that they had been barred from his house.

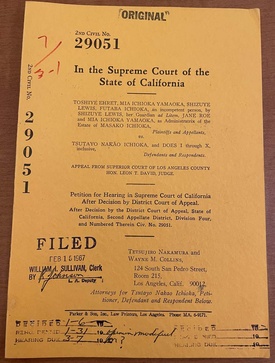

Following Dr. Toshio Ichioka’s passing, the estrangement between the sisters and their stepmother erupted into open conflict. In 1962, Toshiye Ehret, Mia Ichioka Yamaoka, Shizuye Lewis (as Sue was then called) and Futaba Ichioka brought suit in California court against Tsutayo, alleging that property of their late mother Masako, which had been held in trust for them by Toshio during his life, had been appropriated by Toshio and transferred to Tstutayo in violation of the trust.

In the trial court (where Tsutayo was represented by renowned civil liberties attorney Wayne Collins and Tetsujiro “Tex” Nakamura) the case was dismissed. Shizue, acting as her own attorney, brought an appeal. In January 1967, in the case of Ehret v. Ichioka, the California Court of Appeals overruled the trial court’s verdict. (I have not discovered the final disposition of the case).

While in the end their association degenerated into acrimony and legal conflict, the Ichioka women’s fascinating and revealing life histories help enrich and complexify the historical narrative of Japanese American women.

© 2022 Greg Robinson