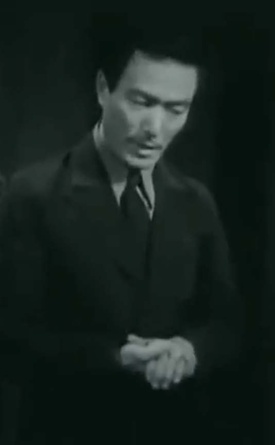

One of the most fascinating, and most poignant, stories of Nikkei performers in the “golden age” of Hollywood is that of Miki Morita (AKA Mike Morita). While he never achieved the stardom of Sessue Hayakawa, he appeared in some 50 films in 1930s Hollywood. He also distinguished himself by his campaign against hostile stereotyping.

Information on Morita’s early life is sparse and unverified. He was born Mitsugi Morita in Nagano, Japan on September 1, 1888, the son of Shinzaburo Morita. In 1907 the 18-year-old “Mitsuki Morita” arrived in Seattle, with his destination listed as Vancouver and his occupation as student. In 1913, when he travelled to Europe, he was listed as living in Ottawa, Canada. Four years later, his draft card identified him as living in suburban New York and working as a butler. By 1923, when he took a trip back to Japan, he was identified as a long-term resident in Los Angeles. According to one source, he performed in silent films such as Souls for Sables (1925) and Broadway Lady (1925), but this is uncertain.

What is known is that he served during this period as manager of a Brazil Study group in Los Angeles, devoted to encouraging Japanese emigration to Brazil. In mid-1927, Morita took a trip to Sao Paulo, Brazil to investigate possibilities for Japanese settlement, and stayed in South America for four months.

One source states that he ran a coffee plantation in South America and that he appeared on the New York stage, but I have found no corroboration for either statement. At some point he again returned to Japan, then arrived back in the United States in May 1931.

By 1931, Hollywood was at the beginning of the sound film era. Mori won bit parts in several movies, most often as a valet or servant (as “the proverbial Japanese butler” in Larry Tajiri’s acid words). He also played a small role as a bandit in the film War Correspondent.

However, Morita remained in obscurity until he was recruited to play a lead role in a Universal Studios production, Noguchi, a pictorial drama of the life of the famous Japanese-born doctor and research scientist Dr. Hideyo Noguchi (which had been the subject of a popular biography by Gustav Eckstein the previous year). Some 45 Japanese actors applied to studio officials to test for the coveted role. After a series of screen tests, Morita was selected, both for his talent and his striking resemblance to the late scientist—one source states that Morita had met Noguchi in New York.

The original plan for a biographical drama gave way to a fictionalized version of the Noguchi story, entitled Nagana, with actor Melvyn Douglas as the main character and Morita in the supporting cast. Nagana is set in the interior of Africa, amid jungles, wild animals, and native Africans. Douglas and Morita play a pair of scientists who are seeking a cure for “nagana,” a deadly sleeping sickness. After developing a serum to combat the dread disease, Dr. Kobayashi heroically tests it on himself, and expires with the parting words, “In the fight of science against disease, some of us must die!”

Nagana was not a box office success, and reviewers divided over the film’s merits. However, Morita gained widespread plaudits for his performance. Critic E. de S. Melcher wrote in the Daily News that Morita “is consistently good and gives much to the dramatic moments of the picture...” Liberty magazine, which rated the picture as a two-star production over all, gushed that the “Best acting of all is done by Miki Morita.”

Despite these positive reviews, Morita was not offered further lead roles, and during 1933 he went back to playing valets and other bits. According to various sources, he appeared in such films as the Loretta Young vehicle She Had to Say Yes and in the political fantasy, Gabriel Over the White House. He also worked with the brothers Sueo and Ikuo Serisawa in their project to produce a community-based film that eventuated in the feature Nisei Parade (1935).

Within months of the release of Nagana, Fox Films approached Morita to star in a screen version of Jacques Deval's Marie Galante, a story of international intrigue and espionage (which would later be adapted into a musical by Kurt Weill). Before deciding on the role, Morita read a copy of Deval’s original novel. The book centers on the activities of Tokujiro Tsumatsui, a Japanese agent who secretly conducts an espionage network for Tokyo in the Panama Canal Zone, while passing himself off as a respectable merchant. Tsumatsui meets Marie, a beautiful French woman, who agrees to work for the Japanese business man to finance her passage back to France. Arrested by military police, she is finally killed. Tsumatsui, heartbroken by Marie’s tragic fate, sends her body home in a white Japanese casket that he had intended to be used after his own death.

Morita immediatelv objected to the project, claiming that Deval's story of Panama Canal intrigue and Japanese espionage would damage international relations. One scene in the book that Morita considered particularly dangerous was of Tsumatsui chartering a ship and purposely running it against the locks in the Canal, in an attempt to ascertain the strength of the sluicegate. Not only did Morita turn down the film, but he proceeded to risk his career by protesting to both American and Japanese authorities. In the process, he explicitly brought up the issue of the responsibility of artists from minority groups to ensure that their work did not reflect negatively on the larger group.

Stung by protests from Morita and the Japanese consulate, Fox executives ordered the script rewritten. The character Tsumatsui became a retired Japanese naval officer residing in the Canal Zone. Although suspected of being the ringleader of a gang plotting to blow up the canal locks (as he really is in the original) he instead cooperates with American agents to protect the Canal. In the end, Tsumatsui joins the brave American investigator, played by Spencer Tracy, to catch the real culprit, who has a gutteral German accent and who looks German. Despite these changes (which outraged author Deval), Morita still refused the role, and when no other Japanese would take it, the part was offered to a white actor, Leslie Fenton.

Morita’s next important project was the Columbia film, Death Flies East (1935) starring Conrad Nagel and Florence Rice, in which he was engaged for a key role as a produce dealer who is in fact a secret agent responsible for transmitting to Washington, D.C. a secret formula which will revolutionize the arms industry. He likewise was in the cast of Grand Exit, a 1935 mystery thriller featuring Ann Sothern, and appeared as “Fuji” in Front Page Woman, starring Bette Davis and George Brent.

Meanwhile, Morita was cast with other Nikkei performers in the screen adaptation of Oil for the Lamps of China (1935). In that film, Morita played a comic Japanese tailor in a scene set in Yokohama. He also played a comic role in the 1934 film The Captain Hates the Sea.

As journalist Larry Tajiri noted, referring to Morita’s performance in Front Page Woman, such was the actor’s talent that “he is given recognition for his brief bit by newspaper reviewers, something rare for the Japanese player who is usually nothing but a Mongoloid anonymity.” Indeed, in speaking of the film, It Couldn’t Have Happened (1936), the Hollywood Reporter noted, “Miki Morita gets laughs as [lead actor Reginald] Denny’s Japanese houseboy.”

The same year, in its review of Isle of Fury, starring Humphrey Bogart, The Hollywood Reporter noted, “There is a good bit by Miki Morita as a Chinese servant.” Soon after, the same newspaper praised Morita’s work in North of Nome as one of the “good supporting performances.” That year, Morita also performed in I live for Love, starring Dolores del Rio; The Spendthrift, with Henry Fonda; The Dark Hour (in which he played a key part as Chong, a budding Chinese chemist); I’ll Name the Murderer; and Kelly of the Secret Service.

The following year, 1937, Morita also carried off multiple roles comic and dramatic, including the inevitable servants. In Leo McCarey’s The Awful Truth, he plays a Japanese valet who exchanges jiujitsu flips with Cary Grant. In The House Across the Bay, he plays the houseboy of Lloyd Nolan’s character. In She Asked for It, he portrays Kaito, a valet. In Women of Glamour (where he was reunited with his “Nagana” costar Melvyn Douglas) he appears as Kito. In Warner Brothers’ The Singing Marine, he is Ah Ling. He acted more substantial roles in a pair of independent features. In Bulldog Drummond’s Revenge, starring John Barrymore, Morita plays Sumio Kanda, a Japanese secret agent. Hollywood Reporter praised him for his “useful bits” in the film.

Conversely, in Border Phantom, Morita appears as Chan Lee, the owner of a Chinese restaurant in a town on the US-Mexico border who is smuggling Chinese women across the border in soybean barrels to be “picture brides” for local Chinese men (the Hollywood Production code no doubt forbade reference to them as prostitutes). A critic in Film Daily referred to Morita’s character as a “suave, philosophical oriental.” Variety, meanwhile, celebrated his break from typecasting: “Morita, about the first time out of many starts [can] appear in a role which doesn’t call for him to be a houseboy or valet.”

After 1937, Morita’s screen appearances dwindled. As with other Nikkei performers, he may have been a victim of popular anti-Japanese sentiment following Tokyo’s invasion of China. In the 1938 film Pacific Liner, with Victor McLaglen, Morita plays a stowaway Chinese laborer. In Big Town Czar (1939) and The House Across the Bay (1940), he plays a domestic. His final screen role was in Hal Roach’s comedy Turnabout (1940).

In that film, as well as portraying Ito, a martial arts expert, he was an advisor for a martial arts scene. (A contemporary news article reported that after leading lady Carole Landis surprised the heavyset director Roach during rehearsals by executing a wrist flip on him, Morita stated proudly, “Miss Landis my very good pupil.”)

In November 1940, Rafu Shimpo reported that actor Miki Morita had received word of his mother’s illness, and had left for Japan. The larger reasons behind his departure are likely more complex. It is easy to imagine that he was frustrated or disillusioned. Whereas Morita resided in Hollywood in the mid-1930s, and worked in films almost without pause, by the time of the 1940 census he was recorded as a guest at the Edison Hotel in East Los Angeles, with no occupation listed. Morita had never put down many roots in the United States, where he faced prejudice and was blocked from naturalization. Conversely, reminiscences of Morita underline his passionate Japanese nationalism—which had once contributed to his support for emigration.

Whatever the case, according to Larry Tajiri, Morita was still in Japan at the time of Pearl Harbor, one year after his departure. Once war broke out, he supported Tokyo’s imperial war machine by becoming a broadcaster for Radio Tokyo. There is little information about his subsequent life, but Tajiri reports that Morita was sent to the Philippines, where he died in 1945.

Miki Morita went swiftly from Hollywood renown to decline and exile. His career as both performer and activist demonstrates both the limited possibilities for prewar Japanese performers in the US film industry and the talent of those who did enter it. It is unclear whether Morita’s challenge to the studio over Marie Galante, and his uncompromising refusal to play Tsumatsui even after the rewrites, hurt his career. True, he was never again cast in a leading role by any major studio. But then, neither was any other Japanese actor of the period. Conversely, Morita continued to be cast in a variety of supporting parts. While viewers can still appreciate his surviving work, it also hints at what greater performances he could have delivered, had he been given greater opportunities.

© 2022 Greg Robinson