In 1921, Otsuka moved to 216 North Michigan Avenue1 following Maruyama’s next business move,2 although the new location was “a less desirable location (than 300 S Michigan Avenue.)”3 In addition, Maruyama changed his business name to the Toyo Importing Company because, according to Beth Cody, “the Toyo Art Shop no longer carried just high-end art, but also included common decorative and household items.”4

When Maruyama’s business began declining, Otsuka had to think of another means for survival and had found possibilities in Florida. Using Post Office Box 101 in the Yamato Japanese colony in Florida, where Susumu Kobayashi lived with his family, Otsuka placed the following ads in Tampa and West Palm Beach newspapers at the end of 1922: “Japanese Gardens Unique and Attractive. Skillfully and Quickly Constructed.”5

Otsuka and Yoneko celebrated their 25th anniversary in June 1922 at the JYMCI.6 After a destructive earthquake hit Japan in September 1923, the Toyo Importing Company was authorized to auction off Japanese and Chinese objects d’art “due to the home office of the Toyo Importing Company in Tokyo and Yokohama being destroyed by earthquake and fire and [the company is] compelled to realize immediate cash.”7

A year later, Maruyama held another auction because “the reconstruction of our home headquarters, Tokyo, Japan, necessitated a call upon us for immediate financial assistance.”8 Amid a city-wide call for Aid for Japan, Yoneko Otsuka participated in the community effort for Chicago Japanese Relief Fund.9

Otsuka’s situation did not improve. Finally, after living in Chicago for about sixteen years, he decided to move to New York City in March 1924. Nearly fifty friends, including Consul Yoshida, came to his farewell party, which was held at the JYMCI.10

Why would Otsuka want to live and work in New York? Because there was another key person who might have encouraged and helped him: a man named Ushinosuke Narahara, who was based in New York City. One source mentions that Ushinosuke Narahara once helped Otsuka improve his gardens with his professional training and knowledge in gardening, which might have been the beginning of their connection.11

Ushinosuke Narahara was born in January 1888,12 graduated from the School for Horticulture in Japan in 1912,13 and came to the U.S. in October 1914.14 He was originally based in New York City, and enlisted in the U.S. Army during WWI from May 1918 to July 1919.15 Before enlisting, in June 1917, he was a gardener working for C. T. Brown of Emerson Hill, Concord, New York.16 The New York address listed in Otsuka’s ad in Art World suggests a connection to Narahara’s business and encouragement for Otsuka to come to New York City.

After he was discharged from the Army, Narahara was employed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York from 1920 to 1943. In 1921, he was assigned to be a part-time curator in the Department of Botany in the newly opened Field Museum in Chicago.17 Narahara certainly could have helped and advised Otsuka during his visits to Chicago. Eventually, in 1924, Otsuka did leave for New York City.

Otsuka’s new Japanese garden business was located at 2021 Broadway in New York, but he didn't stay for long.18 He returned to Illinois in 1926 to build a Japanese garden for the D. Hill Nursery Company in Dundee19 and temporarily lived at 3605 Lake Park Avenue in Chicago.20 By 1930, however, Otsuka had settled in Florida and lived in Daytona Beach as a merchant of Japanese gift goods21 while keeping his landscaping job on a traveling basis.22

But the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition brought Otsuka back to Chicago. The Japanese Garden at the Exhibition was commissioned by Kiyoshi Inoue and based on original plans designed by Tatsui Teien Kenkyusho in Tokyo.23 The local contractor for the project, Masasuke Kawamoto,24 commissioned Taro Otsuka to do the technical work on the garden.25 While staying at Misaki Shimadzu’s JYMCI at 747 East 36th Street, Otsuka worked on constructing the Japanese garden, which was probably his final project in Chicago.

Masauke Kawamoto was a telephone engineer26 from Yamaguchi prefecture who came to the U.S. when he was 18 years old.27 After graduating from high school in Los Angeles,28 he attended the University of Southern California and received a Bachelor of Science degree in Electrical Engineering in 1916.29 It is not clear when he came to Chicago, but we know that he worked at Commonwealth Edison Company in Chicago as an electrical operator by 191830 while staying at Shimadzu’s JYMCI.31

He must have been Christian and was involved with the JYMCI as a board member in the 1920s.32 He returned to Japan in 192633 but came back to Chicago to work as an engineer at Westinghouse in 192934 and was assigned to work for the Century of Progress Fair in 1933.

We only know fragments of Otsuka’s story in the 1930s. He went to Oklahoma for a four month assignment to build a Japanese garden after the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago was over, but was hospitalized due to pneumonia.35

By then, his friend, Tomihei Maruyama had died in Los Angeles in July 1932,36 after closing the Toyo Importing Company in June 1927,37 moving to Los Angeles,38 and running the Cherry Inn in Culver City.39 As if he were following in Maruyama’s footsteps, Otsuka then tried to expand his landscaping business in Pasadena, California.40

Tragically, his wife Yoneko, after supporting her life with Otsuka by engaging in the retail and wholesale importing business for ten years in Florida alone, died in Miami in February 1937.41 After Yoneko’s body was sent back to Japan, Otsuka’s whereabouts are unknown.42

Dr. Keiji Uehara, an authority on Japanese gardening and landscaping whose books are still read in Japan today, visited several Japanese gardens in the U.S. in 1921. Uehara came to Chicago at the end of February 1921 and stayed more than three months to do research on public parks and female horticulturists.43

Uehara’s philosophy had several main points:

1) that gardens in general must be used, not just created to be looked at,

2) that Japanese gardens should be designed with structures that meet practical purposes in a Japanese style, and

3) that designing eclectic gardens that mix western and Japanese styles must be done by trained landscape architects.

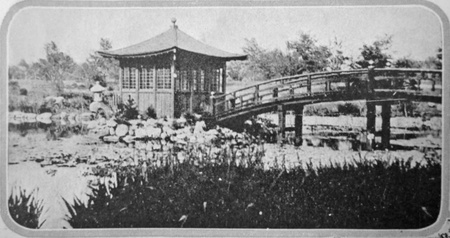

Uehara thought that most of the Japanese gardens in the U.S. were vulgar and unbearable, with a few exceptions. One Japanese garden builder (whose name is unknown) told him that these gardens should be acceptable, as long as they matched American tastes. Unsatisfied with this response, Uehara wrote that Americans who knew the essence of Japanese culture would never be satisfied with such vulgar gardens and that good gardens had harmony in eclecticism.44 One of the few good gardens Uehara praised in his book was located in Lake Forest, Illinois and built by Taro Otsuka for Louis F. Swift, one of the meat packing giants of Chicago.45

Taro Otsuka also used the word “harmony” in his advertisements, as demonstrated in the following example: “Japanese Gardens and Rockeries… planned and developed in perfect harmony in short time…. Gardens are a necessary part of world reconstruction.”46 According to Otsuka, building Japanese gardens was also a way of building world peace, and he thought that all Americans should be invited to Japan. He believed that even the stubbornest anti-Japan critics would become pro-Japan once they went to Japan and touched the warm heart of the Japanese people and the Japanese landscape.

In sum, he thought that aesthetic sentiments could win out over the ugliness of exclusivists.47 Despite his professional and scholarly knowledge, Dr. Uehara could never have understood the meaning that Otsuka, as an immigrant, invested into building Japanese gardens in the U.S.

Notes:

1. Asia, April 1923, Beth Cody unpublished manuscript.

2. Nichibei Jiho, July 1, 1922, 1923 Chicago City Directory, January 1925 Chicago telephone directory.

3. Beth Cody unpublished manuscript.

4. Ibid.

5. The Tampa Tribune, December 7, 1922, The Palm Beach Post, December 29, 1922.

6. Nichibei Jiho, July 1, 1922.

7. Chicago Tribune. October 8, 1923.

8. Chicago Tribune. October 15, 1924.

9. Chicago Tribune. September 9, 1923.

10. Nichibei Jiho.March 29 and April 5, 1924.

11. Japanese Wikipedia for Ushinosuke Narahara.

12. Narahara WWII Registration.

13. Japanese Wikipedia for Ushinosuke Narahara.

14. New York, State and Federal Naturalization Records, 1794-1943.

15. Ibid.

16. Narahara WWI Registration.

17. Shin Sekai March 16, 1921, NY Shimpo, March 5, 1921.

18. Nichibei Jiho, January 31, 1925, May 1, 1926, January 29, 1927.

19. The Herald, (Crystal Lake, IL) May 6, 1926.

20. 1928-29 Chicago City directory.

21. 1930 census.

22. 1932 Daytona Beach City Directory.

23. 1933-nen Shikago Shimpo Isseiki Bankoku Hakurankai Sanka Shuppin Jigyou Hokoku, page 268.

24. 1933-nen Shikago Shimpo Isseiki Bankoku Hakurankai Sanka Shuppin Jigyou Hokoku, page 270.

25. Ibid, page 268.

26. 1930 Census.

27. NY Shimpo, July 31, 1926.

28. Ibid.

29. The Japanese Student, 1917.

30. WWI Registration.

31. List of Visitors to the US Chicago Japanese YMCA.

32. Shimadzu’s letter to Parker/General Secretary of YMCA,February 20, 1924, Chicago YMCA Collection, Chicago History Museum.

33. NY Shimpo, July 4 & 31, 1926.

34. NY Shimpo, June 8, 1929.

35. Nichibei Jiho, December 9, 1933.

36. Rafu Shimpo, July 14, 1932.

37. Nichibei Jiho, June 18, 1927.

38. Ibid.

39. Rafu Shimpo, July 14, 1932.

40. The Pasadena Post, October 10, 1936.

41. Miami Herald Obituary, Feb 20, 1937.

42. Ibid.

43. Yomiuri Shimbun, June 7, 1921.

44. Uehara, Keiji, Tabi kara Tabi e Watari-dori, page 176.

45. Ibid, page 178.

46. The Japan Review, January 1920.

47. Nichibei Jiho, July 19, 1924.

© 2022 Takako Day