Looking at the overall picture of the service industry in those days, we find that Japanese immigrants with the right qualifications reported to be equal to the “splendid record of the older generation of black servants in the South” and thus, were placed in competition with the younger generation of African Americans in the industrious North. At the same time, Japanese people were not treated equally with whites in the polarized “black or white” society of America.

The Chicago Defender expressed their frustration with the competition as follows:

“… Orientals are coming largely into the field of hotel work and are being used as porters in railroad employ. Japanese and Chinese have been employed as cooks in hotels and cafes or engaged as servant in private homes. How embarrassing it must be for a lady guest in a hotel when she has called for the chamber maid to be confronted by a Japanese man!!! The Canadian Pacific has Japanese porters employed on their new transcontinental trains.”1

The Defender reported further frustration about Japanese staff on the Union Pacific Railroad, which they called “The Yellow Peril,” and decried that:

“We do not blame the Jap boys for edging in wherever they can, but the railroad officials who are constantly advertising ‘SEE AMERICA FIRST’ SHOULD EMPLOY AMERICANS FIRST.”2

Regardless of the racially-charged, competitive situation, some wealthy Americans did not hesitate to hire Japanese servants. For example, a banker who lived at 175 Sheridan Road hired six single Japanese staff, four men and two women: twenty-five-year-old M. Misawa, forty-year-old S. Shima as a cook, twenty-two-year-old Kosema as a horseman, twenty-three-year-old Issahora as an upstairsman, thirty-year-old Iaku M. as a ladies maid, and twenty-eight-year-old Fuji as a second maid.3

According to an article in the Chicago Tribune, servants at Franklin McMullin’s house in Highland Park were “almost all Japanese.” Mrs. McMullin had “a Japanese lady’s maid, whose native costume adds another note to the harmony of her beautiful home” and “the chef and his assistant, the butler, and one of the housemen” were all Japanese. The McMullins were “greatly in favor of Japanese help,” and they claimed, “the small, gentle people (were) quiet, quick and efficient.”4

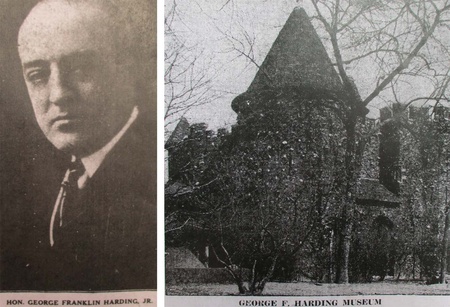

Most likely to keep their Japanese servants happy, one wealthy family even built a cottage for them to live and to cook Japanese food for themselves in.5 Even some of the richest and most prominent residents of Chicago did not hesitate to hire Japanese workers. For example, Milton Kaoru Ichikawa worked at the farm of Louis F. Swift, president of the meat packing firm, Swift and Co.6 Jintoku Higa and Kiyotsugu Tsuchiya worked at the “Castle Museum” of George F. Harding, Jr, a prominent figure in Chicago business and politics. Harding built the museum as an annex to his south side mansion at 4853 Lake Park in 1927,7 to exhibit his “enviable collection of arms and armor,”8 and Higa and Tsuchiya were hired to take care of the artwork.

In response to the number and popularity of Japanese servants, the Japanese Domestic Workers Home9 at 3200 Calumet Avenue was established in 1911 to help Japanese men with their job searches. The Home was managed by Genso Oye, a twenty-five-year-old single man who had lived at Takeda Shoten, a Japanese grocery store with a lodging facility10 in 1910,11 who would become a very successful restaurateur later in the 1920s. He charged “$4.50 per week board. Those out of work and without funds are given food and shelter until they are able to repay. The home’s capacity was 23 and self-supporting.”12 Ken Suzuki was recorded as a resident of the Home in 191113 and later became a chief cook in New Mexico.14 By 1918, the Home was renamed the Japanese Club,15, but was still in operation at 3118 Calumet Avenue, under the management of Toyo Kodaira.16

Japanese workers were also sought out for gardener positions at private homes. The July 3, 1913 Florists’ Review posted a “situation wanted” ad for a Japanese person who claimed that he was a “reliable, all round grower; single, five years experience, private place to take charge of greenhouse and garden preferred, Chicago or St. Louis desired.” Two years later, another ad was posted by a Japanese man who said he was “single, gardener and horticulturist, with nine years practical experience in all branches of gardening, nursery and landscape work, private place preferred.”17

Eminent sociologist Jesse F. Steiner, a protégé of Robert Park at the University of Chicago in the 1910s, explained the relational psychology of Japanese servants as follows:

In Japan the servant occupies a lowly position, but they are made to feel that they belong to the family and share in its interest. A striking characteristic of the industrial life of the Far East is the attitude of personal relationship between employers and workmen. When Japanese are permitted to work on this basis in American homes, they often manifest a spirit of loyalty that arouses the admiration of their employers…I could give a hundred instances of unselfish devotion and loyalty of Japanese servants that could be equaled only by the splendid record of the older generation of black servants in the South. One cannot treat them as one would an English, Swedish or German servant… Unfortunately the Japanese do not usually receive the kind of treatment that would develop this spirit of loyalty, and as a consequence these result in misunderstandings and friction which handicap the Japanese in their efforts to make a place for themselves in the industrial life of our nation.18

Differing somewhat with Steiner’s analysis is Choei Kondo, president of the Chicago Japanese Saving Association, who described Japanese domestic workers in Chicago as “people who are intelligent enough to think of self-improvement and development.”19

According to Kondo, there were four successful photographers, a restaurateur who ran three restaurants, two or three delicatessen businessmen and four tea/coffee merchants and four Chinese restaurant owners, all of whom had previously been domestic workers in Chicago,20 and in fact, in the 1910s, most Chicago Japanese shifted their profession from domestic service to the restaurant business.

Notes:

1. Chicago Defender, August 5, 1911.

2. Chicago Defender, Sept 16, 1916.

3. 1910 census.

4. Chicago Tribune August 25, 1907.

5. Ito, Kazuo, Shikago ni Moyu, page 140-141.

6. World War I registration.

7. Nichibei Jiho, April 21,1928, 1930 Census.

8. The Art Institute of Chicago, Arms and Armor, Highlights of the Permanent Collection, “The Legacy of George F. Harding, Jr.”

9. 1914 Chicago City Directory

10. Day, Takako, “The Chicago Shoyu Story—Shinsaku Nagano and the Japanese Entrepreneurs - Part 1.”

11. 1910 census.

12. Social Service Directory 1915 of Chicago, Department of Public Welfare, Page 98.

13. Chicago City Directory 1911.

14. World War I Registration.

15. Nichibei Nenkan, 1915.

16. Social Service Directory 1918 of Chicago, Department of Public Welfare, Page 105.

17. The Florists’ Review , March 15, 1915.

18. Jesse F. Steiner, The Japanese Invasion: A Study in the Psychology of Inter-Racial Contacts, a dissertation, University of Chicago, page 120.

19. Nichibei Shuho, July 20, 1918.

20. Ibid.

© 2022 Takako Day