Back in the mid-1940s, a Mrs. Lopez called up Kashu Realty in L.A.’s Crenshaw district and asked to speak with real estate agent Kazuo K. Inouye. Lopez lived on Rimpau Blvd in Mid-City and told Inouye that she wanted to sell her house, but insisted that she would only sell it to a non-white homebuyer because, when she purchased the house years before, she suffered the wrath of her neighbors, who took her to court in an attempt to prove that a Mexican American was not legally “white.” (She won the case.) Inouye gladly found a Japanese American family to buy her home, put up a Kashu Realty sign that said “sold,” and that’s when the trouble started.

Soon, rocks were flying through windows of the house next door, which was owned by a Jewish couple. Apparently, a rival broker had hired four guys to break every window of the Lopez house, but in their haste and nervousness, the thugs had vandalized the wrong house. The Jewish couple suspected the man behind the bungled affair was the one they had witnessed standing across the street aring a ten-gallon hat. He stood beside his 1947 Terraplane car with the door wide open, surveying the damaged windows with a look of profound disappointment.

Inouye called the cops and discovered the man in the “Texan’s” hat was a broker on Adams Boulevard. “So, I found out who he was, and I called him,” Inouye recalled. “I says, ‘You know, I was overseas [serving in the U.S. Army during WWII], and I killed a bunch of Nazis and fought for democracy.’” Then Inouye growled, “‘If you step one foot on the property—I got a German luger that I brought back. I’m going to shoot you between the eyes.’ He said, ‘Don’t you threaten me.’ I said, ‘Look it. I’m going to sleep on the porch, and I’m going to wait for you. If you try it one more time, I’ll put you away. Have you heard of a kamikaze? That’s me. Are you afraid to die? I’m not afraid to die. Come on, try me out.’ He said, ‘Don’t you threaten me.’”

Inouye’s “kamikaze” stance apparently worked since he never saw the broker again.

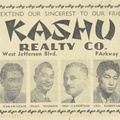

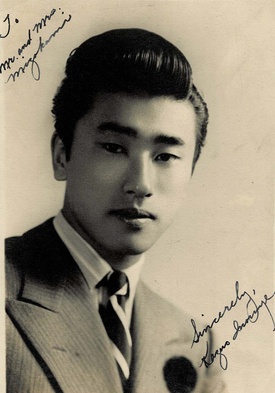

Kazuo K. Inouye was a second-generation Japanese American who made it his business to populate racially restricted Los Angeles neighborhoods with Angelenos of color, thus shaping the culture of the city block by block, for generations to come. He founded Kashu Realty in 1947 and sold a record number of homes to Japanese, Chinese, Black, and Latinx first-time homebuyers in Leimert Park, Venice, Culver City, Baldwin Hills, Monterey Park, and Crenshaw, helping to end decades of racial limitations to fair housing. His get-up-and-go mentality and abundant charm contributed heavily to the success of Kashu, where clients and staff alike described him as boisterous, good looking and ready with a story for every situation.

He was born in Los Angeles in 1922 to immigrant Japanese parents, Zenkichi and Toyo Inouye, and grew up between the cultural cacophony of multiracial Boyle Heights and the itinerant streets of Little Tokyo, where he worked as a produce market swamper. Inouye was determined from the start, learning sumo wrestling from his father and earning champion status as an All City gymnast and a 4th degree black belt in judo while in his teens. Nevertheless, Inouye faced constant racial discrimination, which only fueled his determination to persevere and be at the top. “My father always used to tell me that, ‘You’re just as good as any hakujin, which is American,’” Inouye once reminisced. “In fact, you’re better than them, because you’re Japanese.”

During World War II, he was drafted into the U.S. Army’s segregated, all Japanese American unit known as the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. When the war ended, Inouye was 23 years old. He returned to L.A. and two years later, recognizing his community’s hunger for stability and homes to call their own, he opened Kashu Realty, named for the old Japanese American moniker for “California.”

His real estate company would go on to help change the racial makeup of homeownership across Southern California. Sometime in the late ‘50s, Kashu Realty started to sell houses in West Adams and Leimert Park. The company placed ads in the Japanese American dailies and the African American newspapers like the California Eagle and Los Angeles Sentinel.

As Inouye explained, “One black would move in, and they get so shook up that the whole block would sell. When I went back to my 25 year high school reunion (chuckles), my friends found out that I was Kashu Realty. He says, ‘Hey, Kaz, you’re the blockbuster.’ I said, ‘No, no. I didn’t do that. One black moves in, everybody else wants to sell. I just helped them.’ (chuckles) At one time around the ‘60s, we were selling 50 and 60 houses a month. That’s every day, two and three houses.”

According to historian Scott Kurashige, from 1950 to 1960, the population of Blacks and Asians in the Leimert Park neighborhood grew from a combined 70 persons to roughly 4,200 of each group, plus about 400 Latinx. Over time, Kashu Realty had satellite branches on Wilshire Blvd, Beverly, Hillhurst, Lankershim, and E. 1st Street, plus offices in Sunland and San Gabriel/Monterey Park, where the firm performed similar feats.

Inouye certainly didn’t do it all alone. He recognized that he needed a multiethnic sales force committed to persevere. Over the years, he employed Japanese, Black, Jewish, and Chinese Americans, many of whom were immigrants working two or more jobs in addition to being on the Kashu salesforce. Encouraged, some Kashu office employees, like Florence Ochi and Victor Mizokami, pursued and obtained their realtor’s licenses.

In 1952, Chinese American Bill Chin joined Kashu Realty from his native Detroit and, in a few years, became Inouye’s partner and a real estate legend in his own time. Chin, now 92 and still a licensed realtor, became a fixture in the Japanese American community and married a Japanese American who was born at the WWII Japanese American concentration camp at Rohwer, Arkansas. He’s won all the industry awards, and in 1988, Chin became the first Asian American president of the Greater Los Angeles Realtors Association.

Angelenos of color have a long history of discrimination and displacement that has determined where they could claim their homes, businesses and cultural institutions and shaped their sense of local identity in a practice called redlining. By the time Kashu Realty was founded, racial covenants were still buried deep in the small print of home deeds. Federal law eventually banned the practice, but that didn’t stop vigilantes from committing arson and other acts of physical violence against new homeowners of color moving in, or even their white neighbors who were open to selling to nonwhites. Maintaining discriminatory lending practices through the banks and barring real estate agents from selling homes to Blacks, Asians, other non-whites assured that these redlining practices stayed firmly in place.

“First of all, we couldn’t get a loan from the savings and loan,” Inouye explained, “and the banks wouldn’t lend us no money,” but he learned ways to circumnavigate the system. He built a sales relationship with a wealthy white woman who loaned Kashu money on a first trust deed for early customers, before Western Federal Savings became the first mainstream bank to grant loans to Japanese Americans.

Inouye’s sister and brother in law, Tomiko and Roy Masao Mizokami, started an insurance company to secure fire insurance for new homes (which according to Inouye was necessary since they feared that their neighbors would burn their houses down). Since Tomiko was Inouye’s only sibling, he deeply trusted her with the business and through the years, employed her as an office manager in addition to working together to insure new homebuyers. In 1951, the Japanese community formalized a century-old practice of pooling funds and taking turns borrowing sums (known as “tanomoshi”) to start businesses or purchase property by forming the Japanese American Community Credit Union to assist people needing loans with competitive rates.

Inouye was also keen to work with homesellers who were sympathetic to racial integration. “It was a two-way street,” reminded Daro Inouye, Kazuo’s son, “He’s not just buying houses, he also had to find people willing to sell their houses. Racism can be named and shielded in many different ways and redlining was consistently practiced in the 1950s. Sometimes people would flat out tell you my neighbors won’t let me sell. My father had a lot of doors slammed in his face.” Meanwhile, the government subsidized countless projects constructing suburban homes for whites as they fled Los Angeles proper, yet most people of color struggled for space in either public housing or rentals.

To be continued ...

* This article was originally published on KCET on April 14, 2022.

© 2022 Patricia Wakida