In the literary world, bookseller Karen Maeda Allman is widely known and respected for the bestselling authors she has brought to the Seattle area, for her advocacy for BIPOC authors, as well as for the literary prizes she has judged. I have known Karen personally for a few years now, and always felt comfortable in her calm and assertive presence.

Imagine my delight when I recently found out that Karen had a previous life as the lead singer and lyricist of a Tucson-based hardcore punk rock band in the early 1980s! I had to find out more.

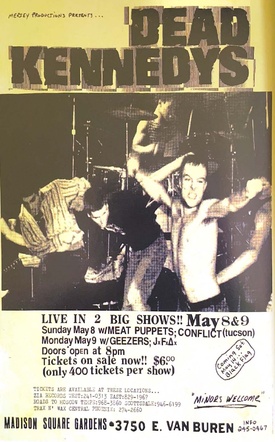

Through some research I found that Karen’s band was called Conflict (later Conflict US, to distinguish it from a similarly named UK band). “Things seemed so desperate at the time,” Karen recalled in an interview with Lance Hahn, “as if nuclear war were right around the corner.” Using the moniker “K Nurse”—she was a psychiatric nurse during these years—Karen wrote and sang lyrics for the band. Conflict US opened for popular punk bands including Husker Dü, Dead Kennedys, and Black Flag. The band is now known as an influential multiracial hardcore punk band, with their one EP Last Hour being reissued in 2015.

Throughout Karen’s life, she has navigated different degrees of inclusion and exclusion in various communities. In Tucson, some people exoticized her and her Japanese immigrant mother. After her punk rock band broke up and she moved to Seattle, some told her that as a biracial (Nikkei and White) woman, her existence “meant the end of the Japanese American community.”

She credits Mayumi Tsutakawa and Bob Shimabukuro as allies who helped her adjust to life in Seattle. The punk rock scene is often thought of as a largely White and male scene. And as a queer biracial woman, she felt excluded at times from predominantly White gay communities.

Nevertheless, Karen has made her own iconoclastic and fascinating path, and it was a great pleasure and honor to talk to her about this one. Because Karen already wrote about her early years and life in bookselling for the North American Post (reprinted on Discover Nikkei - Part 1 and Part 2), I have heavily edited and condensed our conversation here about her life in punk rock. Our conversation taught me about the multiracial (and often whitewashed) nature of punk, about punk fashion, and about the threads that connect her varied careers.

* * * * *

GETTING INTO THE PUNKC MUSIC SCENE, FORMING BANDS

Tamiko Nimura (TN): You have this background in marching band and music and the oboe, and so on. How did you make your way to punk?

Karen Maeda Allman (KMA): Well, my dad played in country western bands and he taught me a little bit about how to play the guitar. So I played the guitar a little bit and then I played at Girl Scout camp, like folk music, but at least I could play some chords.

But I got really interested in the Rocky Horror Picture Show when I was in college and enjoyed that. And I made this friend who lived in Los Angeles [who was] going to fashion design school and she played me some records one day when we were out visiting—a friend and I drove out to visit her—we listened to, I think, the Sex Pistols, maybe Boomtown Rats, and I was like, “Oh that's terrible. Play that again.” And then there was like the Talking Heads and everything and I just thought, “this is just really fun. I just really like this music.”

And I started seeing some shows and there was this bass player named Dianne Chai. It was in a band called the Alley Cats. Alley Cats were kind of the first generation punk rock and rock 'n' roll band, have you heard of them?

TN: I want to say I have, but I’m not sure.

KMA: She was amazing, she was just amazing. She played [bass], not with a pick. She played, almost like jazz, almost like standup bass. She was fascinating. And there were also bands like Black Flag and The Plugs and lots of people of color coming through, actually.

And then I heard of this band [CH3] that had a song called “Manzanar” and I knew what Manzanar was.

So I probably I think I bought that record [Fear of Life] with that song on it and it was by a guy name Mike McGrann. He’s also “haafu,” and I think one of his parents was Nisei, his mom probably.

And I thought, “wow, a song about (we called them) the internment camps, that's really something.” My friend Alice's parents had been in [camp], and we knew all these other people who had been in the camps and I was really excited about kind of the politics of punk.

I really wasn't interested in arena rock, …folk music didn't do it for me really, but I thought I was like, “all this political stuff! And people sing about racism and some people sing about sexism.” And then of course a lot of other stuff that was not like that.

But I just glommed onto the kind of the punk attitude of “think for yourself” and creating your own thing and not worrying about being the most accomplished musician in the world, but just kind of doing it, and in the possibilities for protest music.

We were coming back from a concert actually, it was an Ultravox concert, so not at all punk but because I like a variety of types of music. And we were laughing about listing off the grossest names that you can think of. And then we were like, “oh, we'll start a band” and then we started a band. This band was called the Tampon Eaters and we played very few shows, but it was just really fun.

And then we just disbanded like, you know, so many bands. It just blew up. I was close friends with the drummer and we thought “oh, maybe we could do something. Maybe we could do something again.” So he advertised on through like a local music store and maybe like some papers like The Rocket or whatever paper was going in Tucson at the time—this is all in Tucson, where I went to school—and I thought “yeah, maybe we could have a band.”

So we found a bass player and a guitarist—the guitarist actually moved out to Seattle and he's a graphic designer. He works for the health department now or he was….He designed some kind of smoking cessation program which I thought was funny because he was a big smoker back then. People grow up.

So we started this band and we played a bunch of songs and then that band blew up. The first version of Conflict—We were called Conflict and then there was another band in UK called Conflict so we called ourselves Conflict US. So after that band blew up, it's our major period of time.

We found another guitarist. I was giving blood at the Red Cross and there was a Japanese woman who was the volunteer. We started talking and it turned out that her husband was a professional classical bass player. And they had met when he was on tour with the Philadelphia Orchestra and she was a pianist and he taught her how to play bass.

So she became our bass player and we're still friends, Mariko. She moved away and she became a music director in an Episcopal church. She also taught music for many years. She was the serious musician.

And the guitarist that we had was Mexican and Ukrainian, a young student who became an engineer. He was studying engineering. And then my close friend Nick who had been my friend in the Tampon Eaters, our original drummer, and just was a super close friend of mine for many years. And so we started playing. We were together, I guess, the total time in punk was maybe five years.

But we played some amazing shows. We played with the Dead Kennedys. Dead Kennedys asked us to play on a bill with them in Phoenix. We played with Crucifix and CH3, so it was three bands with Asian American members. A lot of these shows were really small, like 20 people, 40 people, and when it started out it was a pretty friendly scene.

And then of course it got bigger and more violent and more kind of white, and then kind of white supremacist. By that time I was kind of out of there, so…. But at the same time that all this punk rock stuff was happening, I was also coming out [of the closet as a lesbian], I was working for most of this time as a psychiatric nurse in Tucson. And so in the lyrics that I would write… some of that was about directly about my experiences and there's [medical] confidentiality, so it's all very veiled, but is very much there.

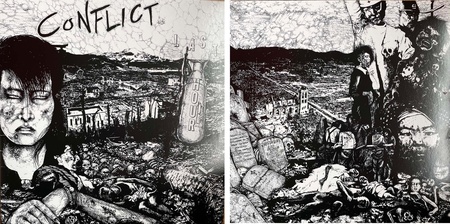

I would write about [issues]. We were worried about a nuclear war then, too, you know, Reagan had just gotten elected. We were playing all these “Rock against Reagan, Rock against Racism” kinds of gigs. I was thinking a lot about what had happened in Hiroshima and the Barefoot Gen comics that had come out, [Hadashi no Gen], and also his personal comic, I Saw It.

So that was the art that inspired our cover. We really released one EP and the moment to EP and the artist is inspired by Hiroshima—but instead of the people depicted in the photos, it's all of our faces [that] are in it, which I think is good. I don't know that I would use that particular imagery in that way now.

I guess I didn't realize that our artist was going to be quite so literal in his depictions, but the album is called, the EP is called Last Hour, which directly refers to that song. So that deals with that but he deals with time, you know, with Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the potential for more nuclear destruction. And at the time there were all these protests, even in Tucson there were protests, anti-nuke protests, and yeah and then one of the songs that I sent you [“Who Will Save Us”], that's also about referring to that kind of [protest.]

So the other message that was really strong and when we were writing about what I was—I wrote all the lyrics so I guess it's me—I wrote the lyrics and the band composed. And our guitarist was Bill Cuevas, he wrote the music but we kind of did a combination kind of thing…And then I had these books of poetry and then I would figure out what fit where.

[The other message] was a feminist message and it was not a real happy place for women at that time, singing in a band especially non-white women who are not like super like “Babe-alicious,” or interested in that. And then there was pushback, you know. I wrote a song called “Fester,” which was about [being] pissed off about all the really sexist violent imagery [in punk] and how people were being treated.

And one of the band styles—I didn't name anybody but they know who they were because they were like “oh I never did anything to her”—OK, I guess it found its mark there.

I came here [to Seattle] to go to graduate school and I thought, “OK, I closed the book on that whole part of my life,” but then it keeps coming back in really positive ways.

I sent records to Germany where they were sold, and also to the UK. There was also a lot of trading going back-and-forth with Icelandic punks. So there was a real international kind of exchange going on. A lot of people heard about us or anybody who was part of the Maximum Rock 'n Roll part of that era, that kind of ethos which was very international, would've heard of us, even though we were very obscure.

We played, not for very long. We were not popular at all, but people heard about us and—come to find out, there were quite a few Asian Americans kind of seeded here and there, who were inspired by what we were doing.

© 2022 Tamiko Nimura