Katsuji Kato as publisher of The Japanese Student and The Japan Review

Kato wrote about the history of early Japanese students in the U.S. in the 1860s1 and a bibliography on American-Japanese relations2 because he thought that “therecord of the past must be preserved, by disseminating accurate information concerning the intellectual relations of the United States and Japan, and contribute to the solution of the so-called Japanese problem in America, the creation of the spiritual and idealistic attitude in the life-philosophy of Japanese students.”3

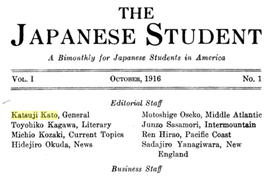

In October 1916, Kato launched the publication of a bi-monthly magazine, The Japanese Student, as a comprehensive compilation of his own awareness of Japanese student issues and activities. The editorial office was at Ellis Hall, 103 Faculty Exchange, University of Chicago, and the editorial staff was made up not only of local Japanese students such as Kato as editor in chief, Shiko Kusama as business manager,4 and Toyohiko Kagawa (who became a world-famous evangelist preacher years later), but also of students from all over the country, including the East, West and Mountain areas. Sales staff were even located in British Columbia, Canada.

Toyohiko Kagawa came to the U.S. in 1914 to study at the Princeton Theological Seminary. After graduating from the seminary in September 1916, he went to Chicago and stayed at the JYMCI.5 He registered at the Divinity School at the University of Chicago in 1916,6 but by March 1917 he moved to Ogden, Utah to do missionary work among the Japanese immigrant community there.7

The Committee on Friendly Relations Among Foreign Students was also involved in the Japanese Student project8 and Charles D. Hurrey was an advisor for the magazine.9 Furthermore, publication was supported financially by the International Committee of Young Men’s Christian Associations.10 The magazine “not only printed messages of a religious nature but also acted as an organ of communication among the Japanese students”11 it touched upon various topics in U.S.-Japan relations, such as society, culture, politics and diplomacy.

According to Kato, the purpose of the publication was as follows:

1) to serve as a mouthpiece of the Japanese students on subjects of vital importance,

2) to introduce the Japanese students to a field of larger usefulness in their respective training and specialization,

3) to act as much as possible as the joint organ of communication for all the organizations that have to do with the Japanese students graduates and friends of Americans schools, and

4) to encourage contributions of the Japanese students to science and service for the development of Japan and America, and thus of the world.12

Publication of The Japanese Student continued for three years, beginning in October 1916. While working on the magazine, in fall 1917, Kato visited Japan “in the capacity of Japanese student secretary for the International Committee of the YMCA” with his wife and two children, Eimei and Yoshi, both of whom were born in Chicago. Kato was determined to bring about better mutual understanding and cooperation, and to prevent, to whatever degree possible, feelings of dissatisfaction for both Japanese students and for American educators.13

Kato planned to lecture on American universities while he was in Japan, so he asked the University of Chicago if he could borrow some films of the 25th Anniversary of the University. Kato wrote to a Mr. Robertson at the Office of President, “Many of the alumni of the University in Japan are anxious to have me bring them when I go... Harvard and Yale have kindly given me the privilege of using their films for my lecture on “American Universities.”14 Robertson answered that they had only one film and could not lend it out for too long as the film was popular, and asked Kato “I wonder if it is possible for me to provide you with lantern slides.”15 It is unknown whether Kato brought the University of Chicago slides to Japan or not.

In Japan, he met educators and lectured more than twenty-five times in various locations. He also had a chance to interview the Minister of Education, as well as Vice Minister of Education, Tadokoro, regarding education for Japanese children overseas.16

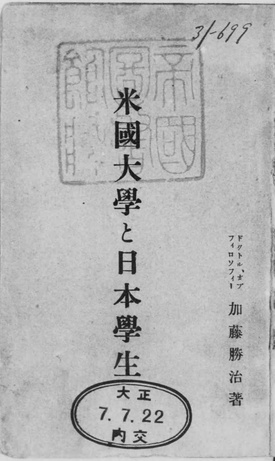

Kato returned to Chicago in January 1918. That year, he published a Japanese book, Beikoku Daigaku to Nihon Gakusei (American Universities and Japanese Students) and included a clear statement on the problems that Japanese students faced in the U.S. In the foreword of the book, Kato declared that “In Japan knowledge about American universities is not always fair and not a few Japanese students among many of them in the U.S. are concerned mainly with acquisition of degrees not academic attainments. Those Japanese students have given unfair impression on American universities, which has been a matter for regret for me, who studied in the U.S.” Kato intended to build better relationships between the U.S.and Japan by publishing the book and by reporting accurate information on American universities to the Japanese. The Committee on Friendly Relations Among Foreign Students supported its publication.17

Around this time, there was a dramatic shift in the political climate for Japanese students in the U.S. According to Roy H. Akagi, one of the editors of The Japanese Student who lived on the Pacific Coast, “the recent conditions and changes among Japanese students in this country reveal several things which challenge the serious consideration of all conscious thinkers. First we have witnessed an enormous increase in the number of students who have an appearance of scattered soldiers without a unified organization. Then, we have followed with interest two distinct student forces, besides the original ones, in rapid ascendancy, namely, the Government Students of Japan, more numerous in the eastern institutions, and the so-called “native sons and daughters,” more marked on the western coast – and how separated these classes appear today!” Akagi declared that “The Japanese Student confidently believes that the time is ripe and that the course is cleared to take a definite step in founding THE JAPANESE STUDENT FEDERATION IN AMERICA.”18

Realizing that he had finally fulfilled his goal of advocating for Japanese students in the U.S. now that the Federation of the Students Club of North America had been established,19 in 1918, Kato enrolled at the Rush Medical College at the University of Chicago to pursue a medical degree. He intended to return to Japan after finishing this degree.20

Meanwhile, The Japanese Student's final publication was the May 1919 issue.21 In November 1919, Kato started a new publication titled The Japan Review. Why did he stop one magazine and start another? The subtitles of both magazines clearly show the transformation in Kato’s intent. While the subtitle of The Japanese Student was“A Bimonthly for Japanese Students in America,” The Japan Review was given various subtitles such as “A Herald of the Pacific Era” and “A Monthly Journal Devoted to the Promotion of Japanese-American Co-operation.”

Obviously, Kato’s focus had shifted from Japanese students to the U.S.-Japan relationship. In his speech on “The Japanese Point of View” at the World Problems Forum YMCA in February 1919, Kato commented on “the relations of Japan and China, Japanese American relations, disposal of Germany’s South Sea possessions and the Siberian questions” and emphasized the importance of a proper understanding of the Japanese viewpoint and that “Japan heartily appreciates the idea of the League of Nations.”22 He asserted that “Japan is friendly to China. Japan merely wants to be a big brother to China, and her aim is one of democratic guidance and service rather than aggrandizement.”23

There were far fewer articles about Japanese students in The Japan Review. The magazine mainly focused on current topics and provided commentary on the Japanese political situation and on broader Japanese ideas for intelligent Americans. Reading the magazine today, one gets the impression that it was an encyclopedia of the U.S.-Japan relationship during the early 1920s.24

According to Kato, “we are determined to make a much better use of our magazine, in disseminating truth concerning present-day Japan, especially her democratic and liberal movements. I am sure we must do something in order to correct some of the misunderstandings which now prevail among most of the Americans, as the result of effective propaganda of both China and Korea.”25 Just from this statement, it is isn’t clear what triggered Kato to change his approach— away from supporting and unifying Japanese exchange students and toward promoting an understanding of Japan in the face of propaganda from Korea and China.

Notes:

1. Kato’s letter to Griffis, dated July 21, 1916, The William Elliot Griffis Collection, Rutgers University, Reel 32

2. Kato’s letter to Griffis, dated Aug 14, 1916, The William Elliot Griffis Collection, Rutgers University, Reel 32

3. The Japanese Student, October 1916, page 1-3

4. The Japanese Student July 1917

5. Shimadzu, Misaki, Beikoku Shikago Nihonjin Kirisutokyo Seinenkai Raihosha Meibo

6. University of Chicago Annual Register 1916-1917

7. Utah Nippo March 5, 7 and 15, 1917

8. The Japanese Student, October 1916

9. Kato’s letter to Griffis, October 7 1919, The William Elliot Griffis Collection, Rutgers University, Reel 38

10. Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 1-3-1-1_49-001, No date

11. The Student World April 1917

12. The Japanese Student October 1916

13. The Japanese Student October 1917

14. Kato’s letter to Robertson, dated June 26, 1917、University of Chicago Office of the President Harper, Judson and Burton Administration Records 1869-1925, Box 53, Folder 20,

15. Robertson’s letter to Kato, dated July 15, 1917, University of Chicago Office of the President Harper, Judson and Burton Administration Records 1869-1925, Box 53, Folder 20

16. Shin Sekai, January 5, 1918

17. Kato, Katsuji, American Universities and Japanese Students, date?

18. The Japanese Student April 1918

19. Cap and Gown 1922

20. Daily Maroon, February 20, 1919

21. The Japanese Student, May 1919

22. Daily Maroon, February 20, 1919

23. Daily Maroon February 21, 1919

24. Okuizumi, page 12

25. Kato’s letter to Griffis, October 7, 1919, The William Elliot Griffis Collection, Rutgers University, Reel 38

© 2022 Takako Day