I was preparing to speak to the Santa Maria Rotary Club about the Central California’s coast April World War II commemoration—the eightieth anniversary of the war, and of Japanese internment here—when I wondered if any Santa Maria Nisei had been among that town's 55 wartime casualties. My hometown, Arroyo Grande, lost 100th/442nd GI Sadami Fujita, among the nearly 1,000 casualties incurred in the rescue of the “Lost Battalion” in October 1944.

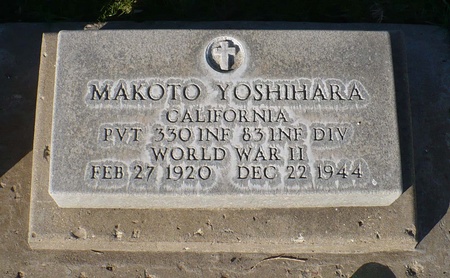

Because of his surname, Makoto Yoshihara was at the bottom of Santa Maria’s list.

He was actually born in Morro Bay; his parents moved to Guadalupe where they ran a boarding house and pool hall. Makoto played football for the Santa Maria Saints, joined or was drafted into the Army in October 1941. His parents, like our Arroyo Grande neighbors, went to the Rivers Camp in the Arizona desert. I knew that Guadalupe had a prominent Japanese-American presence, but the numbers surprised me: Two hundred people were taken from Arroyo Grande, 400 from Santa Maria, but 800 from little, beautiful Guadalupe.

About two and a half years later, the insult heaped on our neighbors would be intensified by the headline that first reported Makoto's fate. From the January 25, 1945, Santa Maria Times:

JAP FROM HERE MISSING

Pvt. Makoto Yoshihara has been reported missing in action in Germany since December 22. He graduated from Santa Maria High School where he was active in football land other athletics. He was called to active duty on Oct. 27, 1941, and was serving with the medical section of the 330th Infantry in France.

That headline, of course, jarring to read. A month later, once Makoto's death is confirmed, the newspaper softens its tone:

JAPANESE BOY FROM HERE KILLED

Pvt. Makoto Yoshihara, who formerly lived in Guadalupe, was killed in action in Germany last Dec. 22, according to word received from the War Department by his parents in the relocation camp, Rivers Ariz.

And you're relieved at the slight change in tone until you read where his parents received that terrible telegram from the War Department. Everyone—everyone—behind barbed wire in the desert would've known almost instantly what had happened to Mr. and Mrs. Yoshihara's son. The tarpaper barracks walls would've done nothing to soften the sound of a mother's weeping for her only child.

The article concludes:

Memorial services for Pvt. Yoshihara were held in the relocation camp Thursday.

Makoto had wanted to be a mechanic—he was, in fact, in a mechanics’ school in Los Angeles when he went into the Army. This must be his high school senior photo. He looks like a serious young man.

Which is why the Army—my father, a World War II veteran, would claim to be surprised by this—did something right. They made this serious young man a medic.

Another surprise came, at least for me, in the article with the insulting headline. Makoto was not a member of the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team, nor—nor was he attached to Military Intelligence in the Pacific, as so many local Nisei GI’s were. They trained at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, in the same tough training that the 4-4-2 endured.

Makoto instead served in the 83rd Infantry Division, the Thunderbolt Division, a unit that had a thoroughly White pedigree—the 83rd was traditionally an Ohio outfit, from the state that produced a batch of mediocre presidents, and here, probably the only Nisei among 10,000 White boys, was Makoto Yoshihara, the medic from Guadalupe, California. The Ohio boys probably had never seen the ocean. Makoto probably never got the chance to see fireflies, one of the natural wonders that make Midwestern summers, despite their oppressiveness, delightful.

He must've been lonely. I can't begin to imagine the needling—the abuse—he must've suffered.

That wouldn’t have lasted long. A friend of mine, a Vietnam-era Pharmacist’s Mate in the Navy, pointed out that Makoto’s comrades would soon come to realize that he might very well become the man who would save their lives once the Division went into combat—a moment that came in July 1944 in Normandy.

The only other local Nisei G.I. I know of that served in a non-Nisei unit was Arroyo Grande's Mits Fukuhara, who served in a tank battalion; Mits and his battalion missed the fighting because the war ended before they could join it.

Makoto didn't miss the fighting; in fact, he saw some of the worst combat of the Americans' war. The 83rd and his regiment, the 330th Infantry, got into a slugging match with the Wehrmacht in the Hürtgen Forest in September 1944 in a horrific battle that would last for two months. The nearest approximate I can think of in the American experience would've been the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864, where dense forest broke Grant's infantry companies down into little knots of men, separated by trees and dense foliage that made it impossible to see each other—or the enemy. Lee's men appeared as shadows, mirages, and disappeared in the smoke, because the muzzle flashes from Enfields or Springfields set the Wilderness afire. The fires burned the wounded alive.

(In 1945, after Germany's surrender, fires swept the Hürtgen and detonated unexploded artillery shells. The war hadn't ended at all for the scores of German civilians killed by buried ordnance that had been intended for soldiers. French bomb disposal experts are still disarming World War I shells from the forest of the Vosges mountains, where the 442nd fought a generation later.)

The battle for the Hürtgen was a debacle. The Americans suffered nearly twice the casualties the German defenders did and they had to pull back and reorganize in December.

Somehow Makoto Yoshihara survived those two months in the forest.

And then, in December, the 83rd Division would face the Germans again in the massive offensive called Nordwind, in what we remember as the Battle of the Bulge, fought during one of the coldest winters in Europe in thirty years.

Makoto didn't have to face that second, epic battle. Somewhere in the not-quite-lull in between, he died. The divisional after-action reports for the day he died, December 22, are bland; they suggested units relieving other units and the straightening of lines; battlefront housekeeping. But when you get down to the battalion level, the reports cite heavy German resistance, nighttime attacks, and cold. Always the cold.

The way he died once again confirms the Army's wisdom in assigning him to the 330th's Medical Detachment. The Santa Maria Times kind of redeems itself, thanks to the Bronze Star citation's wording, in another article from September 1945:

Pvt. Yoshihara, a medical aid man, went to the assistance of a wounded man during an attack and exposed himself to small arms fire of the enemy. Although succeeding in giving first aid to wounded men, he was killed by an enemy sniper before he could return to a place of cover. The initiative, disregard for personal safety, and devotion to duty displayed by Pvt. Yoshihara merits the highest praise and is in keeping with the finest traditions of the military service.

Makoto died saving a brother G.I.'s life because medics—their helmets marked by big red crosses against a white background—were favored targets for snipers; if a German sniper can kill a medic, the five or six wounded soldiers he might've saved will die, too.

Makoto died 5,000 miles away from Guadalupe's row crops, its Mexican restaurants, honky-tonks and the sand dunes and the vivid ribbon of ocean beyond.

His body was returned to America in December 1948 aboard the prosaically-named Liberty Ship Barney Kirschbaum, one of the war's industrial wonders; Kirschbaum's duplicate, Jeremiah O'Brien, made the trip in reverse in 1994, sailing from her berth in San Francisco to England and then to the Normandy coast where she'd done duty in the invasion of the Continent in 1944; O'Brien is the last of the 6,000 ships that supported the D-Day landings.

Accompanying Makoto's coffin on Kirschbaum were the coffins of Orville Tucker of Arroyo Grande, killed on the second day of the Battle of the Bulge—five days before Makoto knelt over the wounded soldier—and Stanley Weber of Oceano, who died the next month in the counteroffensive that erased the Bulge and drove the Germans back.

The coffins, of course, would've been flag-draped. That's an important detail, because belowdecks on Kirschbaum's long voyage home, there were no "Japs;" no Ohioans, no Californians. These were our young men; even in death and even in the eighty years that separate our lives, they remind us that we, all of us, belong to each other.

*This article was originally published in A Work in Progress on March 11, 2022 and slightly edited for Discover Nikkei.

© 2022 Jim Gregory