In 1946, on the initiative of the famed artist Josef Albers, Leo Amino was invited to teach a summer institute at Black Mountain College, the progressive arts school in North Carolina. There he mixed with such luminaries as Jacob Lawrence and Walter Gropius. He would teach another summer session there in 1950. In 1952, Amino joined the faculty at Cooper Union in New York City, where he taught sculpture for some 25 years. In the course of his teaching career, his students included Ruth Asawa, Carl Ludwig Brumme, Jack Whitten, Bacia Edelman, and Kenneth Noland.

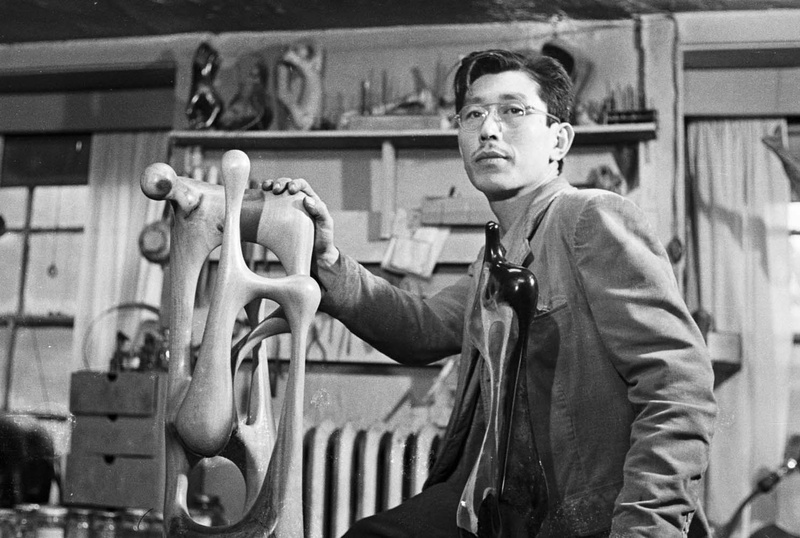

In addition to teaching, Amino continued his experimentation with materials and design.

In the years following World War II, he largely abandoned wood, which had previously been his medium of choice, and sought new materials for sculpture. During the war, he had discovered polyester resin, and he began to experiment with making art out of plastics. His technique, as he developed it, was to model forms in clay, and then cast them in transparent plastic. Unlike with wood sculpture, he could easily add color to these works, placing pigment between or among the layers. Inside the sculptures, Amino would place wire, mesh, coal dust, string, paper, or other objects. He technique of “a sculpture inside a sculpture,” while familiar in glass snow globes, was a novelty in art.

As reviewer P.V.B. brilliantly described the result in the New York Herald Tribune in 1947, “Amino’s modern effects, involving an infinite complexity of shapes, and shapes within shapes, are often intriguing rhythmical designs that shift as the eye moves around them.”

Interestingly, Amino’s work inspired critical comment about the larger adaptability of plastics and new materials, not only for art, but for industrial design. Amino himself took some steps in that direction. In 1951, he designed a lamp, which he dubbed “Spring,” made up of plastic and other materials, with a light inside placed behind a panel with a design. Around the same time, he also designed serving trays and fruit baskets made of sculptured walnut wood and brass rods.

In October 1946 Amino had his first postwar sculpture show, at Clay Club. Howard Devree, who had previously expressed doubts about Amino’s work, this time was solidly complimentary: “Amino’s work reveals a new maturity, less arbitrary use of form and of eccentric subject matter…. Amino is a very courageous innovator in technique and materials.”

At the same time, Amino joined a sculpture show at American British Art Center, mounted to help government officials choose works for the travelling American art shows sponsored in those years by the State Department. While his artwork seems not to have been chosen at this time, its being placed in contention marked the artist’s increased visibility.

In 1947 (the same year that Amino married Julie Blumberger) he held an exhibition at Sculptors Gallery. Soon after, he put on a one-man exhibition of his new plastic sculptures at the Clay Club. It received such acclaim that it was extended.

That same year, his work was accepted by the Whitney Museum of Art for inclusion in that year’s Whitney Annual sculpture show (ancestor of today’s Whitney Biennial). Sculptor Jacques Schnier included a photo of Amino’s work “Spring” in his 1948 book Sculpture in Modern America.

Thanks to his groundbreaking technique of plastic sculpture, by the 1950s Amino became widely known as an artist. He was featured in a dozen Whitney Annuals, and in 1950 the Whitney added his sculpture “Jungle” to its permanent collection. He held a dozen more one-man exhibitions at Clay Club/Sculpture Center during these years, as well as joining in group shows there.

His artworks entered the collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, among others. Meanwhile, he held shows at the Philadelphia Art Alliance, the Person Hall Art Gallery at University of North Carolina, and the Behn-Moore Gallery in Cambridge, MA.

His artwork “Composition” formed part of the Museum of Modern Art’s show Carvers, Modelers and Welders, which toured nationwide during 1953, and his work was included in travelling shows at venues such as the Los Angeles County Museum, University of Wisconsin, Skidmore College, Cornell University, Iowa University, the deCordova Museum, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Shop One in Rochester, NY.

His work was referenced in art history textbooks such as Ray Faulkner’s Art Today, An Introduction to the Visual Arts (1969) and Samuel M. Green’s American Art, a Historical Survey (1956), plus Thelma R. Newman’s Plastics as an Art Form (1964).

Furthermore, while he did not approach the level of celebrity of his contemporaries Alexander Calder or Isamu Noguchi, Amino did achieve some mainstream exposure in this period. Even as the painting techniques of abstract expressionists such as Jackson Pollock were dissected in mainstream media, Amino’s creative process was examined in 1954 in the pages of LIFE magazine. LIFE ran photos of the artist and his sculpture “Hunter,” illustrating his technique for pouring liquid plastic into a mold and baking it until hard. He was likewise profiled, with accompanying photo, in an article on outstanding American and European artists that was published in the New York Times magazine in 1955.

In the course of this period, Amino’s artworks appeared in advertising in such varied periodicals as Esquire, Apparel Arts, and American Perfumer and Aromatics, while his sculpture illustrated the article on “plastics” in Grolier‘s Book of Popular Science.

In 1958, Amino’s design was chosen and cast as the trophy of an annual Miniaturization award offered by Miniature Precision Bearings, Inc. One of his sculptures was even featured as the cover image of a popular music LP, Belmonte and his Orchestra’s 1958 album Rumba for Moderns.

Such popular attention may have been a double-edged sword, in that critics gradually started to downplay the seriousness of Amino’s works. As an anonymous reviewer put it bluntly in the New York Times in 1954, “The merits of Leo Amino’s sculpture…are easily perceived and enjoyed. He finds many clever things to do with his airy abstract shapes and he is an agile craftsman. Not a single piece here betrays either lack of care or mechanical ingenuity. [But] Amino is more of a craftsman than he is a genuinely inventive developer of shapes.”

Emily Cenauer asserted in the New York Herald Tribune soon after that the artist “shows signs of becoming too enamored of material and mannerism.” In the years after 1954, while mainstream art critics briefly mentioned his shows, they ceased to engage substantively with his work.

Even in face of such artistic typecasting, Amino did not stop evolving in his creative process. By the late 1950s, he had begun experimenting with using extruded polystyrene and acrylic, which he featured in his sculptures “The Chalice 1959” and Horizon, 1962.” In the early 1960s, Amino moved on to creating what he called “refractional plastics,” made up of cubelike boxes of clear polyester, into which he placed various geometrical forms.

In 1969-1970, he mounted a pair of one-person exhibitions of his “refractional plastics” at the East Hampton Gallery in New York City. However, whether by choice or circumstance, he seems to have largely withdrawn afterwards from the art scene and from gallery exhibitions.

In 1982, Amino’s wife Julie donated almost 50 sculptures to Rutgers University’s Zimmerli Art Museum. In return, in 1985 the Zimmerli mounted a retrospective show of Amino’s work, his first real museum exhibition. Critic Vivian Raynor, reviewing the show in The New York Times, was as summary and dismissive of the artist’s work as had been the earlier critics: “Unimaginatively displayed, the show is predominantly about technique and comes with a catalogue that discusses little else.”

Leo Amino died on December 1, 1989. His work did appear in scattered shows in the twenty-five years following his passing, notably a 1991 exhibition, Leo Amino: Dream of a Cocoon, at the Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art at Utah State University. Pieces of his also were included in the show Abstract Sculpture By American Artists, 1920-1950 at the Robert Henry Adams Gallery in Chicago (2003), and American Sculpture from the Zimmerli Collection at the Zimmerli Museum the same year.

Still, for a generation, Amino remained all but forgotten. It was not until 2018, with the opening of Polymorphic Sculpture: Leo Amino’s Experiments in Three Dimensions, an exhibition at the Zimmerli Museum curated by Donna Gustafson, that mainstream art critics began to rediscover his work.

In July 2020 Amino’s grandson Genji Amino curated an exhibition, Leo Amino : The Visible and the Invisible at the David Zwirner gallery. In early 2022 the Tina Kim Gallery in New York's Chelsea district offered the show, The Unseen Professors, bringing together Amino’s works with those of his postwar contemporaries Minoru Niizuma and John Pai.

In a thoughtful recent article on Amino in the journal Hyperallergenic Weekend, poet John Yau discussed the “erasure” of Amino’s work, which he speculated was informed by anti-Asian racism. While this is certainly plausible, it is not altogether clear what role Amino’s Japanese ethnic identity played in either his rise or his eventual decline. During his lifetime, Amino did not emphasize his own Japaneseness or point to any Japanese artistic influence on his work. Rather, he presented himself as American, and in 1963 became a naturalized U.S. citizen.

Critics reacted to him in the same spirit. While occasionally his Japanese birth was mentioned, his work was seldom “orientalized”. [One marked exception was an article on art in The American Peoples Encyclopedia Yearbook in 1956 that described Amino as “oversleek,” and insisted dubiously that “His use of black and white recalls the Japanese fu-de (calligraphy brush), and was suggestive of the Pacific.”]

By the same token, the early generations of Asian American art historians did not champion him. Indeed, Amino was not even accorded an entry in the groundbreaking 2008 reference work Asian American Art: A History, 1850-1970. Nonetheless, just as it is to be hoped that the recent spate of attention will help revive public interest in Amino’s outstanding artwork, it is worthwhile to consider the place such work holds within the larger history of Japanese Americans.

© 2022 Greg Robinson