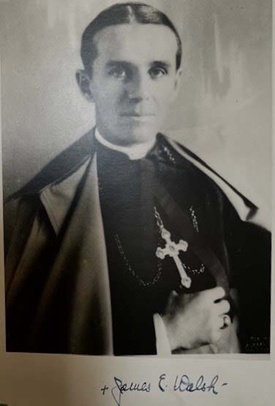

This article forms a part of my continuing series on the presence of the Catholic Church in the Japanese American community. Although a number of clerics—Nikkei and non-Nikkei alike—worked with members of the ethnic Japanese communities of the West Coast, it would be difficult to tell the story of the Maryknolls without mentioning the contributions of Bishop James Edward Walsh, one of the founders of the order. Studying the career of Bishop Walsh helps us to understand the relationship of the Maryknoll Church to the Japanese American community and the spirit of the Maryknoll order from the time of its origins.

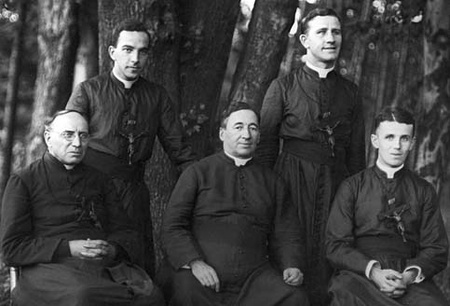

Born on April 30, 1891 in Cumberland, Maryland, James Edward Walsh was the second of nine children of Mary and William Edward Walsh. In 1910, James Walsh graduated from Mount St. Mary’s College and began work as a timekeeper at a steel mill. When he learned about the creation of a new Catholic missionary group - the Maryknoll order – he decided to dedicate his life to the priesthood. Walsh entered Maryknoll’s first class in 1912, and was ordained a priest on December 7, 1915, following three years of training (a short study period compared to that of later Maryknolls). After a period of additional study and language training, Walsh joined Maryknoll’s first mission to China, as one of five missionaries. Arriving in Kwantung (today’s part of Liaoning province) on September 8th 1918, Father Walsh worked alongside Father Frederick Price – one of the founders of the Maryknoll order – and Father Francis Xavier Ford.

Walsh spent most of his career working in southern China. In 1927, Pope Pius XI named Walsh as the first bishop of the Vicariate of Kongmoon (now known as Jiangmen) in Guangzhou, China. Chinese Catholics referred to Bishop Walsh as Wha Lee Son, or Pillar of Truth.

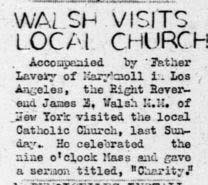

While in China, Walsh returned to the U.S. and undertook numerous tours of Maryknoll’s dioceses. As part of his tours, Bishop Walsh frequently visited the Little Tokyo in Los Angeles parish starting in 1929.Japanese American newspapers like the Rafu Shimpo covered Walsh’s tours and reprinted statements by Walsh. The Rafu reprinted in March 1934 his statement that immigration restrictions against Asian immigrations should end and be replaced with the same quota system used for European migrants. Walsh declared that “The exclusion act was passed hurriedly. It does not represent the general sentiment in this country and is an insult to the Orientals.”

In 1936, Bishop Walsh returned to the United States full-time, and assumed control of the Maryknoll order as superior father. During his tenure, Walsh oversaw the expansion of the Maryknoll order and the start of missions in Latin American and Africa. While Bishop Walsh made occasional visits to stateside parishes, most of his inspection tours took place in East Asia.

In February 1940, Walsh presided over the dedication ceremony of a stone grotto, designed by Ryozo Peter Kado, for the Little Tokyo parish. In addition to making tours of the Los Angeles Little Tokyo parish, Bishop Walsh visited Maryknoll congregations in Seattle in October 1940, and Hawaii in November 1940. While Bishop Walsh was generally well-regarded within Japanese communities, on one occasion his comments sparked controversy. In May 1939, Walsh granted an interview to the Los Angeles Times. When questioned about predicting the outcome of the Pacific War, Walsh proclaimed that China would ultimately prevail against Japan. The Rafu printed an article on the controversy. Bishop Walsh backtracked with an apology, stating that while the war had led many people to consider their spiritual beliefs, nobody could predict its final outcome in advance.

As part of his religious work, Bishop Walsh preached a message of goodwill between the U.S. and Japan. He was so respected for his open attitude that in mid-1941, Walsh travelled to Japan carrying a peace message from Secretary of State Cordell Hull to Prince Konoye of Japan—a last attempt at negotiations before the start of war. In July 1941, the Pacific Citizen reported that Bishop Walsh had visited the Kyoto Parish, and quoted him as stating that he would keep Maryknoll’s parishes in Japan open, despite State Department recommendations that American missionaries evacuate the country.

Perhaps Bishop James Walsh’s most visible contribution to the Japanese American community was his sponsorship of the National JACL. In April 1942, amid the removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans, Mike Masaoka and his associates sought sponsorships from political and religious leaders. Although prevailing public opinion ran strongly against Japanese Americans, and those associated with them faced stigma, Bishop Walsh agreed to sign on as a sponsor of the National JACL organization. According to then-JACL president Saburo Kido, Bishop Walsh represented one of the organization’s first sponsors, and perhaps the highest-ranking religious leader among them. In the period that followed, Bishop Walsh offered various forms of help to the organization. Kido recalled one incident from 1943, at a time when the Dies Committee accused the War Relocation Authority, the agency running the ten concentration camps, of being controlled by the National JACL. Kido noted that the accusations stemmed chiefly from antagonistic articles published in The Denver Post. When the JACL learned that the two sisters that owned The Denver Post were Catholic, its offices reached out to Bishop Walsh, who agreed to intercede with the sisters to change the hostile coverage.

Likewise, in 1944, Bishop Walsh, together with author Pearl S. Buck, ACLU founder Roger Baldwin, and John W. Thomas of the American Baptist Home Mission Society, co-signed a letter in support of the National JACL’s fundraising campaign. According to future Pacific Citizen editor Harry Honda, the letter generated enough funds to launch the JACL’s educational and public relations campaign in the Midwest and Eastern United States.

At the same time of his activism for Japanese Americans, Bishop Walsh also supported other groups like Chinese Americans. On September 4th, 1943, Bishop Walsh presented a statement calling for support of the Magnuson Act of 1943 to repeal the Chinese exclusion acts. Walsh made several visits to China. In September 1944, Walsh travelled to Chunking, China to meet with Maryknoll missionaries still residing in China during the war. On October 2nd, 1944, Walsh met with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek in Kunming to discuss ways that Catholics could help the Chinese war effort. Weeks later, on October 13th, Walsh flew to Kanchow and then trekked by foot across Japanese-held territory to inspect the state of Catholic missions in Kwangtung province. He later returned to allied positions and met with American soldiers.

Aside from sponsoring the JACL, Bishop Walsh assisted Japanese Americans in various ways. On January 22nd, 1944, the Manzanar Free Press reprinted a statement made by Bishop Walsh about providing fair treatment towards Japanese Americans. On February 23rd, 1944, as part of his wartime tour of Maryknoll congregations, he made a visit to Manzanar concentration camp and delivered a sermon.

Shortly after his visit, Walsh returned to China to continue his missionary work. As thanks for his support, the JACL maintained some contact with Bishop Walsh. In May 1946, at a dinner hosted by the JACL in honor of War Relocation Authority director Dillon S. Myer, the JACL invited Bishop Walsh to make a speech. On January 14, 1947, Bishop Walsh and other JACL sponsors met with Mike Masaoka and the JACL’s Anti-Discrimination Committee to strategize in favor of a campaign to repeal discriminatory immigration and naturalization laws.

After stepping down as father superior of the Maryknoll order in August 1946, Bishop Walsh returned to China to continue his missionary work in 1948. Following the end of the Chinese Civil War and the establishment of a Communist government in Beijing, missionaries in China were threatened with imprisonment, and began to leave. Walsh refused to leave, stating boldly that “I will leave China only when the Communists throw me out, or my superiors order me to leave.” Within a short time, Walsh became the only remaining Maryknoll priest residing in China, and found himself under house arrest by the Chinese government in 1951 for refusing to repatriate back to the U.S.

In 1958, citing Walsh’s prewar missionary work in Japan, government officials ordered Walsh arrested as part of a fabricated plot to divide a conquered China between Japan and the U.S.. Convicted of these and additional charges of espionage, Walsh was sentenced to twenty years imprisonment and held in Shanghai.

The Japanese American press printed numerous updates on Walsh during his imprisonment. In December 1965, in lieu of a celebration of Walsh’s 50th year as a priest, a vigil was held at the Maryknoll parish in Little Tokyo. The Rafu Shimpo used the service to report on Walsh’s career, and noted his status as the sole American missionary in China. After attending the service, former JACL president Saburo Kido wrote a reflection on Walsh in the pages of the Shin Nichi Bei, in which he stated that “every person of Japanese ancestry, who was a resident of this country during the war years, will have to be grateful to Bishop Walsh and many others who had helped the JACL during the dark war years when we did not have many friends who spoke up for us.”

Over the ten years following Walsh’s imprisonment, a number of religious organizations called for his release from prison. In August 1970, Walsh, by then 79 years old and frail, was released by the Chinese government. He walked to freedom across the Lo Wu bridge into British Hong Kong. Although Walsh stated that he was interrogated constantly in prison and was forbade from having a rosary, he stated he held “no bitterness toward those who tried to condemned me” and affirmed his love of the Chinese people. The New York Times argued that release of Walsh represented an important signal of thawing relations between the U.S. and China, and paved the way for President Nixon’s 1972 visit.

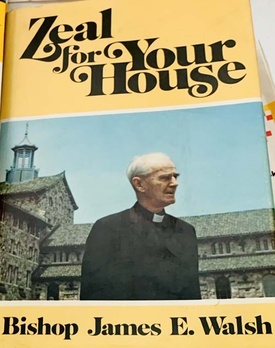

Following his return to the U.S., Bishop Walsh was visited by a number of Japanese Americans. The JACL awarded him a commendation in July 1972. Pacific Citizen editor Harry Honda, who personally delivered the commendation to Walsh, later was mentioned in Walsh’s 1976 memoir Zeal for Your House. After a long career as a missionary and writer of six books, Walsh died peacefully on July 29, 1981 at 90 years old. While Walsh is now mostly known for his role as a leader of the Maryknoll order and as a missionary in China, his work with the JACL and commitment to helping the community during the war years, when association with things Japanese was stigmatized, especially among friends of China, attests to his moral fiber.

© 2022 Jonathan van Harmelen