Last summer my brother was riding a public bus in Palo Alto, California, and, when the driver stopped to let him off, the rear exit door ended up situated right in front of a large tree. My brother, who was visiting from Hawaii, had to make a quick decision: should he shout to alert the driver, or just suck it up and cautiously slide his body around the obstruction. Not wanting to make waves, he opted for the latter. But after he got off the bus, he noticed that that tree was the only obstacle on a long block. Because the driver was white, and given the rise of anti-Asian sentiment in our country, my brother asked me later, “Do you think that driver was racist?”

I told him that I really had no idea. Maybe the driver was new and didn’t know what he was doing, or maybe it was his last day on the job and he didn’t care. Or perhaps he had a hangover and was just trying to get through the day. Or maybe, yes, he was being a bigoted jerk. That, unfortunately, is the problem with many racist incidents—perpetrators have plausible deniability for their actions. If my brother had confronted the bus driver, the driver could have easily said, “Oh, I didn’t realize I was so close to that tree,” all the while gleefully smiling to himself as he inched the bus forward.

My brother and I were both born and raised in Honolulu, but I went to college on the mainland and now live in Boston, whereas he has never lived anywhere but Hawaii. In other words, my brother has always been surrounded by other Asian Americans, and his perceived image of racism is when somebody overtly assaults you by calling you a “dirty J*p.” He’s not really that aware of all the subtle and often hidden forms of racism like “microaggressions” and the countless types of indeterminate occurrences like that episode on the bus.

I have learned to shrug off many of those kinds of incidents, yet they stay lodged in my memory, often surfacing in unexpected ways. Last month I was angered when reading recent news accounts disclosing that the University of Southern California, my alma mater, was not only a passive enabler of racism in World War II; it was an active perpetrator. While other universities on the West Coast were trying to help its Japanese American students get transferred to colleges in the Midwest or East Coast, USC was sabotaging them by refusing to release their transcripts. Even after the war, when those students wanted to continue their education, USC reportedly claimed that some of their paperwork had been “lost.”

This news of USC brought me back to the early 80s, when I was an undergraduate student there. At the time, I knew nothing of the ugly WWII past of my school. But now I’m rethinking a distressing incident that occurred in my senior year. I was in the running to be the valedictorian because I had a perfect 4.0 average. But then, in my last semester, I got a “B” for one of my classes because I had apparently gotten something completely wrong on the final exam. It was a complex engineering problem that would usually take pages of calculations to solve, but I had figured out a much faster way. My professor, however, didn’t seem to understand what I had done and had given me a zero for that portion of the exam, even though I had arrived at the correct answer.

In engineering, there’s usually a conventional solution but sometimes also a more clever way to solve a problem. Say, for example, you had to add all the numbers from 1 to 100. The obvious way is to calculate 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5… But a faster way is to recognize that you can add the numbers in specific pairs that equal one hundred, so 1 + 99, 2 + 98, 3 + 97, 4 + 96… And because there are 49 such pairs in addition to the unpaired numbers 50 and 100, the answer would be 49 x 100 + 50 + 100 = 5,050. Engineers and scientists refer to this faster, nonobvious method as an “elegant solution.” All false modesty aside, I had come up with an elegant solution to that exam problem but my professor hadn’t recognized it.

When I went to him to complain, he gave my paper a cursory look and said something along the lines of, “Well, just because you somehow came up with the right answer doesn’t mean this is good engineering.” I was nonplussed. Did he actually think that I had somehow stumbled upon the right answer by chance? Or maybe he thought I had cheated by copying someone else’s answer?

Ordinarily I would have just let the matter drop, chalking it up to “shikata ga nai,” or it can’t be helped. But my parents were going to be flying from Honolulu to Los Angeles for the commencement ceremony, and I wanted them to be proud of me because I had worked so hard for my degree. Plus, I have to admit that I was peeved at that professor. So, after thinking about it for a while, I brought the matter up with my faculty advisor. He studied my exam paper for a few minutes and said, “Your solution is rather ingenious. Good job! Let me handle this.”

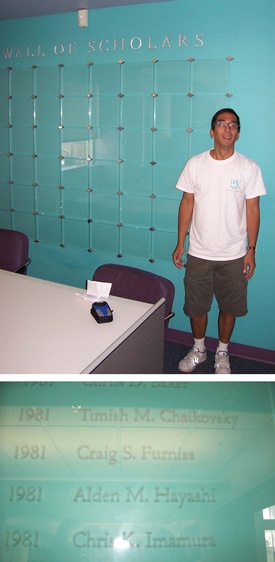

My grade was eventually changed from a “B” to an “A,” but unfortunately I was told that it was too late for the commencement ceremony because the valedictorians had already been selected. I suppose I could have complained but then that would have put the university in an awkward spot. What would it tell the two students who had already been chosen to be valedictorians of our class? And, more to it, I realized that the powers that be would probably not have selected me anyway, so I told myself shikata ga nai and let the matter drop.

Now, even decades later, I’m still not sure what exactly happened. In all my time as an undergraduate, I was one of the top engineering students, so why didn’t that professor give me the benefit of the doubt that maybe I had solved his problem in a faster, more elegant way than he had envisioned? And had it really been too late for the university to consider me for valedictorian, or did the powers that be just not want to deal with the issue? And, of course, the inevitable questions: If I had been a white male, would things have played out differently? That is, would that professor have studied my solution more carefully instead of cavalierly dismissing it, and would USC have done more to make things right than just telling me, “sorry, but it’s too late.”

Of course, there could have been absolutely no racism involved on the part of either that professor or USC, just as there could have been no racism involved with that bus driver my brother encountered in Palo Alto. But here’s the thing that really irks me: Why is it that we Japanese Americans and other minority groups are often the ones spending time replaying such incidents in our minds, wondering whether racism was involved? In a perfect world, it should be the perpetrators who should be doing the self reflection. Really, the burden should have been on that professor, on USC, and on that bus driver to question themselves whether their actions (or inactions) had been motivated or tinged by racism, even if subconsciously. But when I would later see that professor around campus, he never apologized for his gaff and barely acknowledged me. I could kick myself now for feeling awkward in his presence, as if I had been the one who had wronged him by complaining.

When my brother and I talked about that bus incident, I told him that, on the mainland, such occurrences aren’t rare, isolated events. Talk to any Asian on the mainland, I said to him, and you’ll hear numerous such stories.

“Doesn’t it bother you?” he asked.

“Of course it bothers me, but if I dwelled on every potential instance of racism that I encountered here on the mainland, I would have gone crazy years ago.”

“So you just ignore it all?”

“Well,” I explained, “if it’s really blatant, then of course I confront the person. But if it’s borderline or if I’m not sure, then I let it go.”

It’s as if we Japanese Americans on the mainland must constantly run a background “subroutine” in our minds. We question ourselves when potentially racist incidents occur: Did I misread that person’s intention? Am I being too sensitive? Maybe I did something to invite that kind of negative reaction? Should I confront that individual or just let it pass?

Through that conversation with my brother I realized just how much, over the many years that I’ve now lived on the mainland, I’ve learned to “play deaf” when subjected to certain micro-aggressions or potential incidents of racism. But now I wonder whether, at times, I might be tuning out too much. It’s such a tough call, learning when to make waves versus when not. But, given the rising incidence of racism in our country, I know I now need to adjust my subroutine to be more vigilant.

Oh, one final footnote of indignity: when I received my diploma from USC, my name was misspelled. Instead of “Hayashi,” I had become “Hayaski.” I’m sure this was unintentional, and yet it might also have been quite the Freudian slip, disclosing what the university may have wanted all along—for its top students to be white instead of Japanese American.

© 2022 Alden M. Hayashi