Many of us had never been there before. Those of us who had, had not returned since being incarcerated in 1942. So, when our Nisei parents, aunts, uncles, and grandparents finally consented to go, many of us hopped aboard for the 2009 Minidoka Pilgrimage led by Gloria Shigeno and Keith Yamaguchi. Thirty-two of the descendants of Tsuyoshi and Yayoi Inouye joined a total of 127 pilgrims, representing 10 different states as well as Japan.

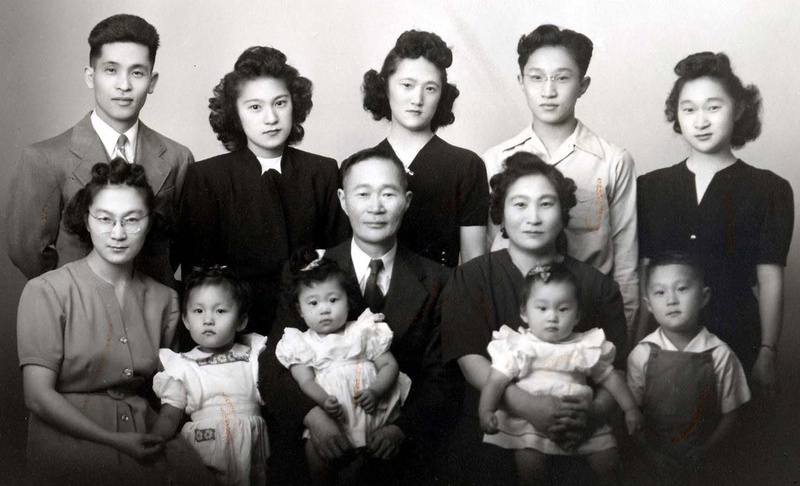

The story of our family is fairly typical of Japanese immigrants. Grandma Yayoi came to Seattle by boat as a picture bride in 1918 from Ehime-ken, Japan to marry Grandpa Tsuyoshi. In 1942, they were operating the State Café at 1st and Madison when Executive Order 9066 was issued. Grandpa was 55 and Grandma was 42. The eldest, Bessie, 23, quickly married her sweetheart, Roy Okada to avoid separation during internment. Ruby, 21, was a junior at the University of Washington and Frances, 19, had just graduated from Broadway High School. Lil was 16 and Howard, 11. Just prior to evacuation, the youngest, Lloyd, had an ear infection and required hospitalization. The doctor who had come to the house carried the baby in a blanket to his car because the parents were unable to leave the house after 8pm due to the curfew imposed upon those of Japanese ancestry.

During the 3 years of internment at Minidoka, only Grandpa, Grandma, Lillian, Howard, and Lloyd remained the entire duration. Bessie, Roy, and baby Diane left camp for Ontario, OR to pick sugar beets. Ruby left after only 4-5 months to finish her undergraduate degree at the University of Texas, one of many schools outside the West Coast exclusion zone that offered to take some of the Japanese American students. Frances worked in Jerome doing housework for an Idaho family.

Our pilgrimage to Minidoka included family members ranging in age from 4 to 88 years. Many of us felt the urgency to attend since the Nisei generation was quickly disappearing from our lives. We were not quite sure exactly what was in store for us; we just knew that it was time.

The Minidoka National Historic Site is a 33,000 acre area which once housed approximately 13,000 internees from Alaska, Washington, and Oregon. Very few of the 600 buildings still remain, although the Friends of Minidoka and the National Park Service are working together to maintain and recreate the site to promote education.

Entering the preserved barracks at the Idaho Farm and Ranch Museum triggered many memories for the former internees. Most Nissei felt the palpable presence of their Issei parents and understood the sacrifices that were made and hardships endured during the war. Many of us crowded into one of the family rooms which held 6 rusted cots and a potbelly stove to hear reminiscences from our Nisei relatives. Ruby recounted the story of the doctor taking Lloyd to the hospital. Howard told of a time when he and his friend arrived home to find the family barracks empty and Grandpa’s Bull Durham tobacco enticing them. He and his friend took a square of toilet paper, folded it in half, rolled up a cigarette, then pondered how they would disguise the smell. They conjured up the idea of blowing the smoke into the potbelly stove! He also told of how he and other school boys removed the knots in the wood to peek into adjoining barracks.

The actual Minidoka camp site elicited additional recollections, although the landscape is now a lush green compared to the arid sagebrush vegetation that originally surrounded the numerous barracks. Entering the root cellar, Howard recounted tales of picking peas with a friend and chanting “jan-ken-po” (rock-paper-scissors) to see who would get to add the other’s pickings to his own to earn a payment of a few cents for a full basket. He also told of a particularly mean teacher who had punished him for crying out when a bully tormented him in class. These were some of the stories that many of us had come to hear from our families before they were lost forever.

The “talk story” sessions on the pilgrimage were another means of sharing camp experiences with family members as well as with others who attended out of interest for past injustices to minorities and civil rights violations. Many were surprised by the depth of emotion that was felt upon recollection. However, with the retelling of the past, internees often found it to be a way of purging themselves of long-held resentments. In addition, a panel of Idaho residents shared stories with the attendees of some of their fond memories of the Japanese. Surprisingly, many of these people remain grateful to the evacuees for their hard work and integrity to make their lands cultivatable and profitable. Bill Vaughn recalled visiting a museum in NY, many years later, and seeing a book of the furniture of George Nakashima. It triggered a vision of a young man working their land and carving greasewood in his spare time. He made an effort to contact him and found out that yes, this man HAD worked his father’s land in the most profitable year ever. They made plans to reunite in Idaho within a year; unfortunately, Mr. Nakashima died before their meeting.

The closing ceremony at the Minidoka National Historic Site was particularly moving and poignant. Rev. Brooks Andrews, son of Rev. Emery Andrews of the Japanese Baptist Church, told of his father moving their family to Twin Falls to be “near my people.” The Honor Roll of former internees who had fallen in battle were read and commemorated. The NVC (Nisei Veterans Committee) and the local VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) provided the Honor Guard and gun salute. Paper darumas were distributed for pilgrims to make wishes for the future or to honor the past.

For our family and others, it was an opportunity to uncover and share the past. Many found memories that they didn’t realize still existed. Some didn’t know exactly why they came, but they left with a sense of purpose and understanding. Others found a history lesson of injustice that provides an example for future generations. Regardless of exactly what was experienced, it was hard to come away empty-handed. There is too much that remains for it to be ignored or neglected.

URL: Minidoka Pilgrimage

* This article was originally published in The North American Post on July 1, 2009 and edited for Discover Nikkei.

© 2022 Geraldine Shu