What is Nikkei? I was born and raised in Kanagawa Prefecture, and when I think back, I first became aware of the term "Nikkei" when I was a student. The exchange student from the United States who taught me English was of Japanese descent. At the time, I first recognized him as a so-called half-Japanese person, and didn't pay much attention to the fact that he was Nikkei.

After that, I became a reporter for the Mainichi Shimbun and worked in Shizuoka for five years, but during that time I had almost no contact with foreigners and did not encounter any events or people related to Japanese people. After that, I quit my job and decided to stay in the United States for a year. When I went to an English conversation school in Tokyo to prepare, I met an American teacher with a Japanese face and a Japanese name. He was completely different from the Japanese people who were good at English, and I wondered, "Is he Japanese or American?"

In America in 1986

My next encounter with Japanese people was when I lived in the United States for a year from 1986. When I was doing my internship at the Daytona Beach News Journal newspaper in Daytona Beach, Florida, a city on the Pacific coast, an elderly Japanese couple named Furuta had seen an article about me in the newspaper and invited me to dinner.

Furuta-san is a second-generation Japanese born in Hawaii, and his wife was born in Japan. Japanese people are rare in Florida, so Furuta-san treated me with a sense of nostalgia and was very kind to me. I received a similar invitation from a group called "Sakura-kai," which I believe is made up of Japanese women living in Orlando, where Disney World is located. They are women with American husbands, and their husbands seem to have invited me because they are interested in Japanese culture. They are people who have decided to make America their second home, and so they could be called Japanese-Americans.

During my stay in Florida, I took a month-long trip around the continental United States in a counterclockwise direction. It was a budget trip relying on friends of friends, and in one of my trips, Omaha, Nebraska, I stayed at the home of a local Japanese person. Omaha and Shizuoka are actually sister cities, and I was able to stay with this Japanese person, who became the liaison for the sister cities through my connection from my time as a newspaper reporter in Shizuoka. It was at this time that I learned that Japanese Americans played a role in connecting Japan and the United States.

In San Francisco, I visited the North American Mainichi Newspapers, which is related to the Mainichi Newspapers, through an introduction from a friend from my time at the Mainichi Newspapers. It was the first time I saw a newspaper in America whose main readership was the Japanese community. An elderly Japanese executive at the newspaper offered me a room in his apartment, and said, "Feel free to use it as you wish. There's a phone and I'm happy to provide you with some alcohol." I was so grateful for his hospitality.

Perhaps it was because I worked in the media, or perhaps because I was traveling alone and seemed unreliable, and of course because I was Japanese, but all the Japanese people I met were kind and friendly.

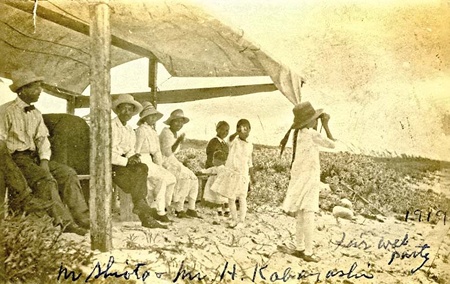

I also drove around Florida, and one day I learned about the existence of a road called "Yamato Road" that connected to a Japanese settlement called "Yamato Colony" in South Florida. However, at the time, my first priority was to learn about grassroots American society, so I had no interest in Japanese things and left it at that. It wasn't until much later that I changed my mind and decided to write about this colony.

The "No No Boy" incident

After that, I didn't meet any Japanese people for a while, but in the 1990s, while I was doing a reportage on the coast of Japan for a magazine, I learned of the existence of something called "Amerikamura" in Mihama Town, Wakayama Prefecture. It was so named because Japanese people who had come to Canada from there during the Meiji Period to work in the fishing industry returned to Japan and built Western-style houses, and it had become a historical tourist spot. During this research, I happened to meet a Japanese-Canadian family who had come from Canada to visit the graves of their ancestors, and we talked. They told me that a large Japanese community had formed in Canada, where they had immigrated.

In 1995, I traveled to several places in the US and interviewed several "Japanese" who had started businesses there. I was attracted to their determination to spend their lives in the US, regardless of whether they were a former businessman who manufactured and sold tofu in Denver or an Amami native who started a transportation company in San Francisco, or to their struggle alone, unrelated to any corporate organization. I myself have worked as a freelancer without the backing of any organization, and I empathized with their adventurous lifestyle. These people, who came to the US after the war, would be what we would call "Shin Issei" today.

A few years later, I had the opportunity to face Japanese Americans head-on. I found a book called "No-No Boy" in a used bookstore, which is about a young second-generation Japanese American living just after the end of the war, and I was drawn to the author, second-generation Japanese American John Okada, and the world he created. As a result, I met many Japanese Americans in Seattle, where the book is set, and learned about the story of Japanese Americans throughout history.

Soon after I started my research, I learned that immigrants and Japanese-Americans were being studied in academia, including in literature, and that they were attracting interest from many quarters. At the same time, I joined a group called the Japanese American Cultural Research Association, which was made up of people interested in Japanese American culture, and was able to broaden my horizons. At the same time, I deepened my research on the Yamato Colony in Florida, which had long interested me, and this led me to learn more about the Japanese immigrant community in America.

I was also helped in my reporting by the long-established Japanese newspaper, Hokubei Hochi, in Seattle, and developed a close friendship with the owner of the paper, Tomio Moriguchi. As a second-generation Japanese, he was a driving force behind the growth of the local Japanese supermarket, Uwajimaya. I also visited Ehime Prefecture, where the family originated, several times to interview the Moriguchi family.

My involvement with Japanese-language newspapers in the US has also developed into relationships with Japanese-language newspapers in Brazil and other parts of Asia, and at one point I was involved in regularly posting articles from these newspapers to Japanese readers on the web. Through these articles, I learned that there is a history and present that can be lumped together as Nikkei in South America, Europe, and South Asia, including Brazil.

While reporting on Japanese people in this way, I came across Discover Nikkei and have since been writing several serial articles for them.

That is the overview of the Japanese people I have encountered, most of whom are in the world of Japanese America. I am not specialized in Japanese society or immigration issues. However, Japanese America has come to occupy a significant proportion of the topics I cover. Naturally, then, I have developed an affinity for people and matters related to Japanese people and Japanese America. Conversely, I have received feedback from people who have read what I have written, which has sometimes led to new discoveries.

This exchange of knowledge, with its effects and reactions, is fascinating, so from next time I will try to take up any topic related to Japanese people that comes to mind.

© 2022 Ryusuke Kawai