Outside defenders of Japanese Americans during World War II, especially those in positions of power, were rare. Issei and Nisei did, however, receive various forms of assistance from a circle of “old Japan hands,” white Americans who had lived in Japan before the war and had become familiar with Japanese culture. These included such diverse figures as Protestant missionary Galen Fisher, Catholic priest Leopold Tibesar, naval agent Kenneth Ringle, diplomat William Castle, and (once he was freed from confinement in Japan) former U.S. Ambassador Joseph Grew.

While they differed strongly in their attitude toward Tokyo’s foreign policy and the war in China during the prewar years, their affection for Japan and the friends that they had made there inspired them to help Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor. Fisher led a Fair Play committee in Northern California to campaign against mass removal. Ringle submitted a report to Naval Intelligence in January 1942 that endorsed the loyalty of Japanese Americans, and argued against exclusion. Father Tibesar testified publicly in favor of Nikkei loyalty in Spring 1942, and visited the camps to administer the sacraments. Castle pushed universities to offer aid to Nisei students after mass removal.

One particularly important member of the “old Japan hands” was Bradford Smith. A native of New England, he lived in Japan for five years during the 1930s, and became known for writing literature about Japanese people. As the head of the “Japan desk” at the Office of War Information, he was the staffer responsible for recruiting ethnic Japanese to aid in the war against Japan.

His wartime service led him to offer public support for the rights of Japanese Americans, and in the postwar period, he devoted himself to writing a popular history of Japanese Americans, with help from a two-year fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation. The product of his efforts, the 1948 book Americans from Japan, was one of the first serious studies of Japanese American history.

William Bradford Smith was born in North Adams, Massachusetts on May 13, 1909, the son of William Wallis and Josephine (Cady) Smith. He was descended from the Pilgrim father William Bradford. After enrolling at MIT as an undergrad, he transferred to Columbia University, where in 1930 he graduated with B.A. degree and served as salutatorian. He remained at Columbia after graduation, and there received an M.A. degree the following year.

Unable to find a job in the United States, in 1931 he took a job at Rikkyo (AKA St. Paul’s) University, a Christian university in Japan. Just before leaving for Japan, he married a fellow Columbia graduate student, Marian Collins.

Although Smith later admitted that he had known effectively nothing about Japan when he arrived, he threw himself into exploring Japanese society. Smith and his wife lived in a Japanese home during their first few months in Tokyo, and he later claimed to have learned enough Japanese “to get around.” They thereafter took a house in Ikebukuro and established themselves as part of Tokyo’s foreign colony. They held dances at home and joined literary clubs. Their son Alanson Smith was born in Tokyo in 1933.

As professor of English at Rikkyo, Smith made contact with his students by revamping the curriculum to better attract their interest. Meanwhile, he produced a new handbook of English and American Literature designed for a mainstream Japanese audience. It was published in Tokyo in 1935. In a sign of his new reputation, in 1934 Smith was invited to become lecturer in English Composition at Teidai (Tokyo Imperial University).

Even as he interacted with Japanese people, Smith held himself out to Westerners as an expert on Japanese society, and wrote articles on Japan for such publications as Esquire, Scribner’s, The Saturday Evening Post, and Coronet. He reviewed numerous books on Japan for the New York Herald Tribune.

In June 1932 he contributed a long article on literature in Japan (illustrated by Issei artist Chuzo Tamotzu) to the Herald Tribune’s Sunday edition. In his article, Smith lauded the rise of a generation of young Japanese who spoke English, read American literature and were interested in modern culture.

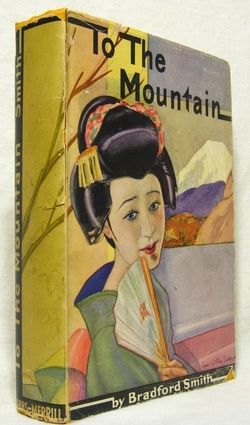

Smith’s informed sympathy for the Japanese was reflected in his first book, the 1936 novel To the Mountain. The novel, published by the publisher Bobbs-Merrill, tells the story of Kimi-Chan, an innocent 15 year-old girl who is sold into prostitution by her peasant family as a way to keep from starving. Once installed in a bordello in Yoshiwara, she meets Mr. Yamano, a vulgar nouveau riche businessman who has made a fortune selling oil. They have a sexual relationship, and she becomes attached to him. However, before he can purchase her as his mistress, she is rescued by a Christian Army officer who frees her and brings her to live respectably in his house. There Kimi-Chan meets and falls in love with Shigeo, a westernized university student who turns out to be the son of the rich merchant. Unable to marry, the two lovers are trapped, and their love ends in sorrow. To the Mountain includes scenes of life in contemporary Japan, including student riots, young soldiers departing for Japanese-occupied Manchukuo, and social relations across class lines.

The book was widely advertised, and it made the Los Angeles Times bestseller list. Critical reaction was intense and mostly positive. The youthful Alfred Kazin, reviewing the book in The New York Times, wittily referred to it as “a tragedy of manners.” While uncertain about the quality of the love story itself, Kazin credited the author for making it at least seem plausible, and noted approvingly that “about the story he has arranged some shrewd pictures of contemporary Japanese life.”

John Fujii, writing in Rafu Shimpo, countered that apart perhaps from the book’s usefulness as a guide to Japanese geography, it had little to recommend it: “The plot is threadbare, the characters are too sketchily drawn, and the style is a bit slow for the modern reader.”

In 1936, Smith returned to the United States, and took up a position teaching English at Columbia University. In 1940 he switched to Bennington College in Vermont. Even as he taught classes, he continued his literary activities (which he claimed made up nearly half his income).

His second novel, This Solid Flesh, published in 1937, centered on the marriage between Masao, a westernized Japanese man, and Margaret, a white American woman. Reviewers spoke respectfully of its portrayal of Japanese society and the issue of interracial marriage, though some found its characters one-dimensional. (Shio Sakanishi, the renowned scholar/administrator at the Library of Congress, commented acidly in the Washington Post on the portrayal of Japanese women, “To those who know a little about the East they are types rather than individuals.”)

The Nisei press praised the author’s attempt to dramatize the conflicts faced by the couple’s hapa child Ruth, who goes off to study in the United States. Roy Takeno, writing in Kashu Mainichi, stated that he was intrigued by Ruth’s “inability in a crisis to identify patently with the Americans or the Japanese.” Reviewer “U.P.,” writing in the Nichi Bei, called the novel “a penetrating and a very human story of tortured lives during an era of cultural and economic upheaval.”

Smith’s third novel, American Quest (1938), a Preston Sturges-type narrative about a discontented executive named Quest (get it?) who decides to wander the highways and see America, attracted much less attention than his Japanese stories.

In the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack and the outbreak of the Pacific War in late 1941, Smith was invited to take a public role as an expert on Japan. He responded with a set of talks on “Our Enemy-Japan,” as well as a series of magazine articles. His “Letter to the People of Japan,” published in Kiwanis magazine in February 1942 and then excerpted in Reader’s Digest, expressed his understanding that the average Japanese had not wanted war, but noted that war had come, and warned prophetically that it would be the most devastating conflict in the history of Japan, since the powerful American people would seek total victory. “We have something to fight for; you have nothing.”

Smith followed this with a pair of articles that appeared in Amerasia magazine during early 1942. While they purported to be objective studies, they were in fact exercises in propaganda. “The Mind of Japan,” which appeared in March 1942, claimed that the Japanese character was reducible to “Shinto, Kodo, and Bushido,” that is, to Emperor worship and a samurai code of loyalty that outweighed the rights of the individual.

“The symbols by which Japan lives are the symbols of a culture which has ever thought in terms of the individual soul and mind and destiny. The dignity of man as man, the personal freedoms for which we have fought and are fighting again have no existence in Japan.”

Smith’s article received widespread public exposure, and was reprinted in full in the Congressional Record by California Republican Rep. Carl Hinshaw (an outspoken proponent of mass exclusion of Japanese Americans).

Shortly after, Smith published a second article, “Japan: Beauty and Beast.” In it, he sought to explain how ordinary Japanese people, who seemed to love beauty, could commit barbarous acts such as the “Rape of Nanking.” He resolved this apparent contradiction in terms of the different values that made up the “national character” of the Japanese. Among these values, he insisted, were uncontrolled sexuality, disregard for human life, and the absence of a religion based upon high ethical and spiritual principles.

© 2022 Greg Robinson