Japanese Acrobats in 1904. (Library of Congress, Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division)

One of the main reasons for the popularity and attraction of Japanese troupes in the U.S. was the inclusion of small children in their performances. For example, Kitamura’s young daughter was named Peach Blossom and her smile was very attractive to the American audience.1 The Tetsuwari troupe “members received their training from the time they were youngsters. They were taught how to use their feet and legs almost as they would their arms and hands.”2

One of them, Yosari Tetsuwari, whose first visit to the U.S. was a trip to Lincoln, Nebraska in 1909, was only ten years old. Because he had studied at an American missionary school in Tokyo, he served as an English interpreter in the various cities the troupe visited. His young age, combined with his being able to act like “a grown-up man with large experience” attracted a lot of attention from Americans.3

An article in the March 6, 1908 Freeport Journal-Standard provided the following analysis of the situation with foreign children:

“The chief reason for the overwhelming preponderance of foreign talent in the American circus lies in the practical exclusion of children from the stage and ring in the United States. So many of the states have laws forbidding the public appearance of children under sixteen that theatrical managers hesitate to produce any play with a child in the cast. As acrobatic feats require early and severe training, the American is practically cut off from this way of earning a living and poor families sent their children to work in cotton mills or mines.”4

What encouraged Japanese entertainers to settle down in Chicago? The answer might be found in two common characteristics. One was their age; many entertainers were young children when they set foot in Chicago for the first time. For example, Kinzo Kaneko came to the U.S. at the age of ten,5 Ichisuke Ishikawa was around thirteen or so,6 and his brother Tatsu was only seven, assuming that he came to the U.S. with Ichisuke. They experienced Chicago at a young and impressionable age, when their lives were just beginning to take shape.

The second common characteristic of Japanese entertainers who permanently settled in Chicago was the high numbers of interracial marriages; many specifically chose white women, either American or European immigrants, as their spouses. Marriage is one of the first steps to settling down in a new country, and a non-Japanese spouse gave these migrants easier access to the larger community, beyond their ethnic community enclave.

Although these entertainers were born in Japan, many of them came to the U.S. in the early stages of their lives against their own free will. America became the only place where they grew up and over time, discovered themselves and learned to exercise their power of self-determination. Regardless of their profession, which required constant travel, they were neither “vagrant” at heart, nor “fugitives” escaping from the Japanese nationalistic ethnic identity. Instead, they were Americans, and their free spirit eventually made them the cornerstone of Japanese American communities in the U.S. Once they were granted citizenship, they legally became some of the earliest “Japanese Americans.”

The first Japanese in Chicago to become an American citizen was Michitaro Ongawa, in 1884. Ongawa came to the U.S. in 1871 when he was eleven and became a theatrical entertainer, performing with his American wife in the 1910s.7

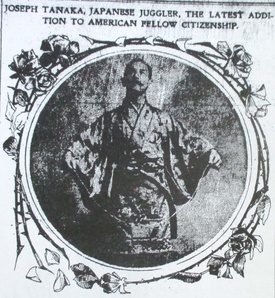

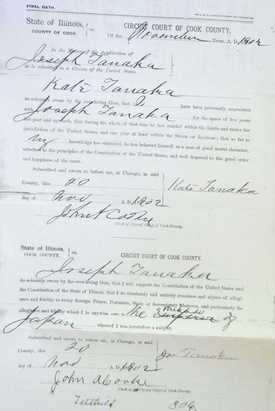

Another Japanese to become an early American was juggler Joseph Tanaka, who came to the U.S. in 1887,8 when he was about thirty two years old, and married a white Canadian woman named Catherine around 1890.9 Tanaka was naturalized in Chicago on November 20, 1902.10 His becoming a U.S. citizen was the subject of a sensational newspaper report that included a large photo of Tanaka, with the caption: “the latest addition to American fellow citizenship.”11

Judge Richard Stanley Tuthill explained his rationale for granting naturalization to Tanaka as follows: “Chicago holds the proud distinction of creating a precedent in regard to the vexed point as to whether the statute which excludes Chinese from becoming American citizens applied also to the Japanese.”

He thought that allowing the statute to refer to the entire Mongolian race, as a judge in California had, “is too wide an interpretation of the law” and declared that “as long as the Japanese who apply to me are respectable and well conducted I shall never refuse them naturalization.”12

Takashi Yamagata was another entertainer who found a home in Chicago. An acrobat, Yamagata was born in Nara around 1883 and came to the U.S. for the first time in 1895 at around age twelve. For many years, he travelled between Japan and the U.S. almost every year, but by 1907 he was in residence in Chicago at 3019 South Park Avenue.13 Three other Japanese acrobats arrived in Chicago with Yamagata on the Grand Trunk Railroad, after having departed from Port Huron, Michigan in 1907. They were Seijiro Emori from Saitama, age ten, Mineji Katagiri from Niigata, age seventeen, and Sute Yoshimura, a forty three-year-old widow from Osaka. They all came from different hometowns in Japan because the network of entertainment companies recruited acrobats and collected children from poor families all over Japan to train them for overseas performances. The Akimoto troupe, who came to Chicago in 1895, was one of them.14 As a result, these Japanese children, who were taken away from poor parents because they could not support them in Japan, lived in Chicago as well.

Entertainers in the Chicago Japanese American Community

In 1902, the Japanese newspaper in New York, Nichibei Shuho, ran an advertisement to recruit Japanese entertainers. The call was as follows: “We need Japanese magicians, acrobats, Sumo wrestlers, Jiu Jutsu and others for two-year contract. Send resume and desired salary.” The employer was listed as A.I.C., located at 20 Bishop Court, Chicago.15

In 1905, while Japan was still involved in the Russo-Japanese War, there was an exhibition of Japanese theatre at Chicago's Sans Souci Amusement Park (Cottage Grove Avenue and East 60th St.)16 The troupe that staged the show had originally come to the Midwest to perform at the St. Louis Exposition in 1904, and then came to Chicago. Kikuyoshi Sakamoto, who managed the troupe, had arrived in Seattle on June 21, 1904, on the same ship with several other Japanese, all of whom were headed for St. Louis.

Originally a merchant who came to Seattle in October 1901, Sakamoto represented a patriotic group, whose purpose was to cheer on Japanese soldiers, to help the Japanese Red Cross, and to aid the families of fallen soldiers. Beginning in July 1904, Sakamoto recruited members for the troupe, which would tour the U.S. and Europe. Sakamoto’s job was to provide a positive picture of the Russo-Japanese War and depict the bravery of the Japanese army and navy to the world through theatrical performances of jiu-jutsu, kendo, and sumo.17

However, thanks to the relatively consistent availability of these entertainers in Chicago, Japanese residents could attend and easily enjoy professional performances of Japanese acrobats whenever they held even small gatherings. For example, when the Chicago Japanese Association held a meeting at a Japanese goods store (185 State Street) run by H. K. Tetsuka to celebrate the Japanese victory in the Sino-Japanese War, “a troupe of clever little acrobats did a few wonderful acts of skill and agility.”18 In 1910, when local Japanese celebrated the emperor’s birthday, the Wakahama troupe was invited to provide the entertainment.19

However, there were also reports of discrimination toward Japanese entertainers by other Japanese. When fifty-eight Japanese came to Chicago on a large business delegation touring the world in April 1908, the Committee of the Association of Commerce of Chicago took them to the Ringling Brothers’ Circus at the Coliseum after dinner. The Committee probably expected to see the visitors’ faces light up, happy to find their own countrymen in Chicago, but “curiously enough, the Japs paid scant attention to the acrobats and performers of their own race.”20 We can only assume that the Japanese visitors might have been ashamed to see their countrymen in a circus.

Regardless of the status of entertainers in the Japanese hierarchical mindset, there was one Japanese entertainer who was rumored to be the richest man in Chicago. It was said that Japanese entrepreneurs begged him for financial aid and investments in their projects. This man was Kumataro Namba.21

Notes:

1. Chicago Tribune, July 19, 1904.

2. The Butte Miner, May 1, 1916.

3. The Lincoln Star, July 5, 1909.

4. Freeport Journal-Standard, March 6, 1908.

5. 1900 census.

6. World War I registration, 1930 census.

7. Day, Takako, “Michitaro Ongawa: The First Japanese American Chicagoan - Part 1,” Discover Nikkei, December 7, 2016.

8. 1930 NY census.

9. Ibid.

10. Certificate No. R-80 P125 Alien; Chicago Record-Herald, November 22, 1902; Japanese American Commercial Weekly, December 6, 1902; Japan Weekly Mail, March 14, 1903.

11. Chicago Record-Herald, November 22, 1902.

12. Ibid.

13. Michigan Passenger and Crew Lists 1903-1965.

14. Miyoshi, Hajime, Nippon Sakasu Monogatari, page 239.

15. Nichibei Shuho, July 26, 1902.

16. Nichibei Shuho, July 1, 1905.

17. Ibid

18. Chicago Tribune, April 26, 1895.

19. Nichibei Shuho, November 19, 1910.

20. Chicago Tribune, April 10, 1908.

21. Nichibei Shuho, May 23, 1914.

© 2022 Takako Day