One of the new breed of Japanese entertainers who came to stay was Fukumatsu Kitamura, a juggler from Fukui. The Kitamura Troupe was founded exclusively for overseas tours and their first U.S. tour, which included a stop in Chicago, was in 1890.1 They returned to Chicago in 1901 as the Kitamura Imperial Japanese Troupe of acrobats, with seventeen members,2 including Kitamura’s wife, Hisa, age thirty-seven, and his daughter, Kane, age eighteen, who were both jugglers.3 Kitamura chose New Jersey as his base over the next few years4 and returned to the Chicago Opera House in 1904.5

In 1908, Kitamura left show business and opened a Japanese grocery store in New York, Takeda Kitamura Shokai, which expanded its import business to include Japanese art goods.6 Takeda Kitamura Shokai had a branch in Chicago as well.7 But Kitamura died suddenly in May 19138 and his death led to the closing of the Chicago branch of Takeda Shoten.

In Chicago, Japanese actors/actresses, foot jugglers, and performers were regularly recorded in the census between 1900 and 1940. The 1900 census listed three actors: Hiro Okabe, age nineteen, a single woman; K. I. Ingimoto, age forty-three, a single man; and K. Kinzo, age twenty-three, a married man.

Okabe and Ingimoto’s address, 1817 South Clark St, must have been a boarding house because more than sixty actors, actresses, musicians, and theatre agents from all over the country lived at this same address. Two of these Japanese residents must have been members of an American troupe or minstrel show. Although we can’t be sure whether it was the same Okabe or not, according to a report, “Okabe’s Japanese troupe of rubber boned artists” performed at the Majestic Theatre in Chicago in 1907.9

Actor K. Kinzo, aka Kinzo Kaneko, was listed in the 1900, 1910 and 1930 censuses, which means he lived in the Chicago area for at least thirty years. He was born in 187510 and came to the U.S. in 1887,11 when he was only ten years old. He married a white Illinois woman, Lilian, in 189712 and by 1930 had been naturalized. At age sixty-five, he still worked as an entertainer.13

The 1910 census listed twelve Japanese entertainers, in addition to Kinzo Kaneko, who lived at a house on California Avenue. Other Japanese entertainers listed in the census were Froyd Yoshida at E. Van Buren Street, George Okura and his daughter, Elvira, M. Hatsu and Harry Harada at Clybourn Avenue, the four Ishikawa brothers at Sangamon Street, Otra Namba, and Toki Murata at E. 71st Street, and Michitaro Ongawa in Oak Park. Okura, Ishikawa, Namba, and Ongawa eventually made Chicago their permanent home.

Foot juggler George Okura was listed in the census from 1910 to 1940. He was born in December 1874,14 came to the U.S. in 1896,15 married Meta, a German woman who was also a foot juggler, and had a daughter with her, named Elvira. He registered himself at the United Fairs Booking Bureau in Chicago and found work through them.16 After he ended his acrobat career in the late 1920s,17 he opened a Japanese goods store at 3929 Irving Park Street in around 1926.

One of the members of Okura’s troupe, an acrobatic cycler by the name of Harada, also stayed in Chicago and gave a performance on Japan Day at the All-American Exposition in 1919.18

The Ishikawa troupe of acrobats were brothers: Ichisuke, age twenty-three, Kame, age twenty-one, Masu, age twenty, and Tatsu, age seventeen.19 Their acrobatic feats were praised as “sensational and daring.”20 They toured and performed on circuits such as the Norris & Rowe Circus,21 but their base was in Chicago, especially for Ichisuke, who lived in Chicago for more than twenty years— from 1910 until the 1930s.

A theatrical performer, Ichisuke was born in Ibaragi in 188622 and came to the U.S. in 1901.23 He married a Czechoslovakian by the name of Katherine in October 1909 in Decatur, Texas.24 As a member of the Western Vaudeville Association,25 he was based in Chicago, where he raised two sons and two daughters, all born in Illinois; Frank, born in 1911, Mabel in 1913, Julian in 1915, and Katherine in 1917. By 1920, the three other Ishikawa brothers had left Chicago, and only Tatsu kept Ichisuke’s address at 7300 South Sangamon Street, although he was actually registered with the United Booking Office in New York.26

According to the 1930 census, forty three-year-old Ichisuke was divorced and lived with his children and granddaughter, Jeannette, at 6333 Harper Avenue. His first son, Frank, age nineteen, became a vaudeville actor.27 After Ichisuke, his second son Julian, and Kane, his brother from New York, went looking for opportunities to perform in Quebec City, Canada in September 1932,28 Ichisuke most likely changed his base to New York,29 but his children all stayed in Chicago with their mother. Frank later served in the U.S. Navy and Julian served in the Army in 1942.30

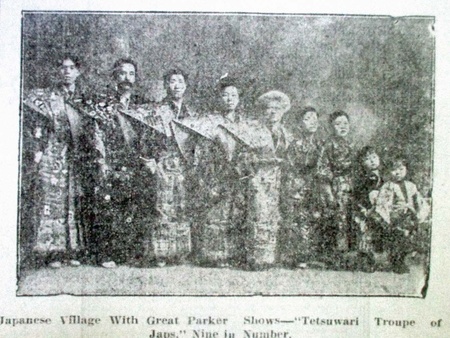

Tetsuwari Troupe

The 1920 census recorded sixteen Japanese entertainers in Chicago, three of which were women. Like Okura, Ishikawa, and Ongawa, entertainers who had settled down in Chicago, there was another well-known Japanese troupe family in the city: the Tetsuwari family. The Tetsuwari family members were Yoshi, age forty five, Shina, age forty three, their daughter Uki, age sixteen, their son, George, age fourteen, and a second son, Kami, age twelve. Kami was the only family member who was not an acrobat. They lived at 1931 George Street in Chicago.

Probably because she was young and cute, in 1915, Uki Tetsuwari was interviewed by a reporter in Decatur, Illinois when she was ten years old and performing as a tight rope walker.31 Although Uki told the reporter that she was born in Chicago, the 1920 census showed that she was in fact born in Arkansas, her brother George in California, and Kami in Ohio; these various birthplaces provide evidence of the troupe’s tour destinations after Yoshi and Shina came to the U.S. in 1902.32

Shina Tetsuwari was also interviewed by the media in California in 1906.33 According to the article, Shina had been born an albino in Osaka. When she was ten years old, some Americans brought her to San Francisco and sold her to the circus for acrobatic training. Although she was lucky enough to go back to Japan, she eventually returned to the U.S. because, as an albino, she was not accepted in Japan. She married Tanyo Tetsuwari, who she met in San Francisco, but lost him in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

No one actually knows the real story, but if we accept Uki’s story that her vaudeville family returned to Chicago every winter after spending summers on the road, that they performed vaudeville in the winters, that she went to Chicago public schools, and that she had a Japanese girlfriend whose parents owned property in the city,34 we can assume that Uki Tetsuwari and her family must have settled in Chicago by around 1915.

Founded in Osaka in about 1831, the Tetsuwari troupe was the first Japanese troupe to arrive in the U.S. in 186635 and the young acrobat who met and fell in love with a white girl in Chicago was a Tetsuwari member.36 One of its smallest performers was a very popular acrobat known as “Little All Right,” or Rinkichi Tetsuwari, (most likely not related by blood to Yoshi Tetsuwari. In some traditional arts, students who train under the same master adopt their surnames) who had his photograph, “Rinkichi in Kimono and shoes, with Japanese umbrella and fan in his hands,” taken in Chicago. That photo can be found today in the Harvard University library.37 In the 20th century, various Tetsuwari offshoot groups traveled and performed around the country, in states like Colorado38, Nebraska39, and Kansas.40

Newspaper coverage also shows that offshoot acrobatic troupes came to Chicago as early as around 1907,41 to Moline in 1910, Rock Island in 1911, and Sibley in 1912. The actor Yakichi Tetsuwari (again, not likely a blood relative) lived at 427 George Street in Chicago in 190742 and stayed there, although the house number changed from 427 to 1931, until 1912.43

A Tetsuwari performance in Chicago was reported in the August 10, 1912 Chicago Defender as follows: “the original Tetsuwari Japanese Family were splendid and their scenery was (as is ever the work of the Orientals) beautiful.”

A Tetsuwari performance was a part of the entertainment at the Travelling Engineers’ Convention held in Chicago in 1913.44 Around this time, Yoshi Tetsuwari, not Yakichi, was listed as living at the same George Street address in Chicago.45

By 1917, three more Tetsuwari family members had joined Yoshi Tetsuwari at the 1931 George Street address. They were Joe Tetsuwari, age twenty three, Tomi Tetsuwari, age twenty one, and Fuji Suwami, age unknown. Joe was an actor from Osaka and had a contract with the Western Vaudeville Circuit. Tomi was an acrobat and employed by Yoshi Tetsuwari.46 Fuji was a thrilling acrobat who could “make the hair of an audience stand on end” by “standing bolt upright, [and then] shoot from the second balcony down a rope to the stage.” In a pledge of loyalty, he patriotically declared that he would fight for Uncle Sam “whenever they called him.”47

In addition to these men, performers Denkichi Sato and I. Teramae also resided with the Tetsuwari family.48 Teramae and the Tetsuwari troupe performed at the Chicago YMCA “Japan Night” in August 1916.49 From the records, it appears that Yoshi Tetsuwari led a troupe of at least nine members in Chicago in about 1917.

Notes:

1. Ito, Kazuo, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-shi, page 65.

2. The Inter Ocean, August 11, 1901.

3. Washington, Arriving and Departing Passengers and Crew Lists.

4. 1910 census.

5. Chicago Tribune, July 19, 1904.

6. Zaibei Nihonjin Shinshi-roku, page 82.

7. Day, Takako, “The Chicago Shoyu Story—Shinsaku Nagano and the Japanese Entrepreneurs - Part 1,” Discover Nikkei, February 17, 2020.

8. Nichibei Shuho, January 25, 1913 and May 17, 1913.

9. The Joliet News, January 8, 1907.

10. 1910 census, 1920 census.

11. 1900 census.

12. 1900 census.

13. 1930 census.

14. World War I Registration.

15. 1910 census.

16. World War I Registration.

17. 1930 census.

18. Nichibei Jiho, September 3, 1919.

19. 1910 Census.

20. The Daily Review, February 9, 1908.

21. 1910 Kentucky census.

22. World War II Registration.

23. Katherine Ishikawa naturalization record.

24. Ibid.

25. World War I Registration.

26. World War I Registration.

27. 1930 census.

28. Canada Immigration Service Report.

29. World War II Registration.

30. Katherine Ishikawa naturalization record.

31. The Decatur Herald, June 10, 1915.

32. 1920 census.

33. The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 24, 1906.

34. The Decatur Herald, June 10, 1915.

35. Schodt, Frederik, Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe, page 14.

36. Ibid, page 168.

37. Ibid, page 175.

38. Shin Sekai, January 18, 1907.

39. The Lincoln Star, July 5, 1909.

40. The Leavenworth Post, May 25, 1910.

41. The Times, August 19, 1907, The Joliet News, October 22, 1907.

42.1908 Chicago City Directory.

43. 1913 Chicago City Directory.

44. Chicago Examiner, August 13, 1913.

45. 1914 Chicago City Directory.

46. World War I registration.

47. Star Tribune, June 23, 1918.

48. World War I registration.

49. Nichibei Shuho, August 19, 1916.

© 2021 Takako Day