The surname “Namba” appears in the 1910 Chicago census, documenting thirty five-year-old Otra Namba, troupe manager, and Toki Murata, a twenty six-year-old contortionist, as residing at 1227 E. 71st Street in Chicago. Otra had come to the U.S. in 1890 at the age of fifteen, and Murata in 1900.1

While it is not known when Otora Namba came to Chicago, Otora, a vaudeville actress, had married a Japanese animal trainer, Yosaka Kudara, in Mexico in 1894. They came to the Pan-American Exposition held in Buffalo in 1901, but the marriage ended up in divorce, as Kudara abused her and threatened her life, according to Otora. Kudara was suspicious of the relationship between his wife, Otora, and Kumataro Namba, not knowing that Otora and Kumataro were brother and sister.2

According to an article in The Buffalo Times, Otora and Kumataro were born in Matsuyama, Ehime in Japan. Otora was adopted at the age of five or six by one Kojiro Iriye, who taught her to be an acrobatic performer and brought her up as his own child, until she came to America in 1894.3

Otora’s brother, Kumataro Namba, was born in 1872.4 He had been in show business since he was six years old and had made overseas performance in many countries,5 possibly with Otora. Kumataro was rumored to have married a Swedish woman, but she died before 1904.6

Interestingly, Kumataro and Otora were vocal politically about their loyalty to Japan during the Russo-Japan war. First Otora insisted that there would be no war between the two countries because Russia was afraid that the United States and England would help Japan.7 Once the war started, they collected donations from audiences and sent them, along with a part of their salary, to a Japanese war fund set up by the Japanese government to support Japan in the war. Namba found the sentiment of the United States to be decidedly pro-Japanese, and explained that “Everyone say[s] Russia [is] no good, we like [the] Japanese [the] best.”8

In 1910 Kumataro Namba was on a tour that performed in the Eastern U.S. (including New York)9 and Europe when the census was taken, so he is not recorded as living in Chicago in 1910.

Murata was born in Japan in 188010 and lived in Chicago for nearly twenty years. Records show that he performed at the Grand Theatre11 and that he worked for the Western Vaudeville Association, located in the Marsh Majestic Building.12 By 1906, the Namba troupe seemed to have established themselves in Chicago.

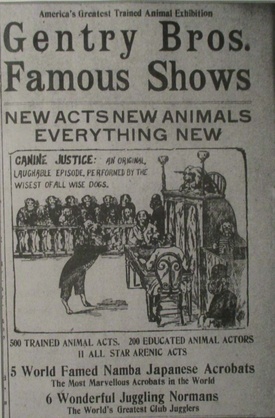

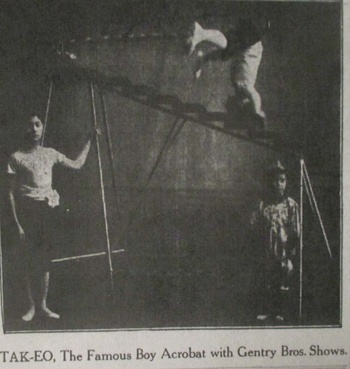

A local newspaper in Illinois introduced one of the early Namba family members as follows: “Suka Sami, the Japanese acrobat, with the Nambas Imperial Japanese Troupe, is a man with a remarkable history. Last year Suka Sami joined the Nambas Imperial Troupe, and has been exclusively engaged to appear in this country with the Gentry Brother’s Famous Shows United.”13 Suka-Sami appeared on the stage with Tak-eo, “the only living performer who goes upstairs on his head without the aid of hands or feet.”14

It seems that the main attractions of the Namba troupe were its stunning performances by young children. An article in the May 18, 1912 Chicago Defender said that “the Namba Japanese troupe were always great. Their acrobatic stunts were marvelous, but these little people take to such work as a duck to water and one can always look for the very cleverest tricks from them and never be disappointed.”

In fact, the Namba actively collected child performers, crossing the Pacific often to bring back children from Japan. For example, in November 1905, a “Mrs. Namba,” a thirty-year-old acrobat, brought four children to the U.S. via Vancouver, Canada. They were K. Sato, age eleven, I. Nakane, age eleven, Miss Sakamoto, age nine, and K. (Kaichi) Arayama, age seven.15 This “Mrs. Namba” could possibly have been the Otora Namba, who was recorded in the 1910 census.

The Namba troupe participated in the Japan-British Exhibition held in London from May to October 1910. Kumataro Namba led a sixteen-member troupe, which included his new wife Iku, his “sons” Kyonosuke (aka Kiyo) and Kaichiro (aka Kaichi), and Kaichi Arayama. Of the fifteen performers, nine were under fifteen years old.16

His wife, Iku, age twenty-two, was born in 1889 and had come to Seattle in 1907 when she was eighteen years old.17 Their “sons,” Kyonosuke and Kaichi, were born in Kyoto in August 189618 and November 1898,19 respectively. They were only fourteen and eleven years old when they performed in London.

Kiyo Namba, sometimes known as “Tokio Namba”, appeared to be half Japanese and half Caucasian20 and was well known as “the only gymnast in the world who jumps up a flight of stairs on his head”21 His performance was described as follows: “First he stands on his head on an elevated platform at the foot of a flight of ten stairs. The rise of each step is about four inches. With his legs and arms in the air he draws himself down a little, then springs upward and slightly forward.”22

In June 1912, Kumataro Namba was called by the authorities in St. Joseph, Missouri to come from Chicago to certify his guardianship. Three children—one boy and two girls from the Namba troupe, a 14-year-old boy named Kaichi Namba and two girls named Tome Ireya and Sei Kakamoto, age fourteen and eighteen respectively—escaped from their road manager. They complained that they were beaten and kicked many times, and received only thirty five cents a week for all three, while the manager received 150 dollars a week for the act that the children performed. In excusing himself, Namba told the authorities that he sent the children's pay to their relatives in Japan.23

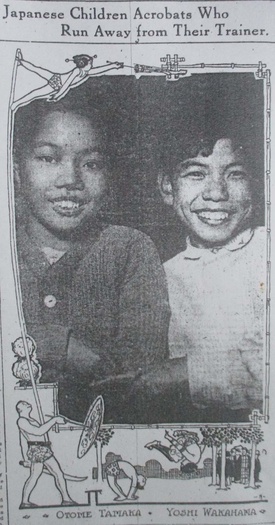

On another occassion, November 14, 1912, the name “Kumataro Namba” appeared in both Chicago newspapers and in Japanese newspapers on the West Coast. Two acrobats, a 14-year-old boy named Yoshi Wakahama and a 15-year-old girl named Otome Tanaka, escaped from Namba and were turned over to the Hyde Park Police Station after they were found performing acrobatics and collecting money. They were performing in front of a big crowd at East Sixty-Seventh Street and Stony Island Avenue, at the edge of Chicago's Jackson Park.24 The Chicago Tribune published a photo of their smiling, happy faces.25According to Yoshi, they had been sold into slavery by their parents to Kumataro Namba for $25, for a full seven-year contract.26 Namba brought them to the U.S. around 1907, when Yoshi was ten years old. Otome, from Osaka,27 was only nine when she arrived in the U.S., and said that she was Namba’s wife’s sister.28

The two claimed that Namba's training methods were very cruel and that he exhibited them for his profit only. At the police station, Yoshi reported:

“Otome had a very difficult trick to perform. She had to stand on her head on top of a tall bamboo pole while one of the performers crossed the stage bearing the pole upright. She fell to the floor, striking on her head and injuring herself, and since then she has been afraid of the trick. Namba would whip her when she refused to perform or practice it, for it was one of the best tricks of the act. Then Namba would whip us when we failed in the tricks. And he would give us but one meal a day so we would not grow. Otome grew so afraid of Namba and of the trick that she suggested we run away, and we slipped away from Namba’s house yesterday morning.”29

Otome had a long gash in her forehead.30 Namba’s gymnasium was at the back of his house, and was sometimes called “a chamber of torture.”31

Kumataro's wife Iku Namba and their adopted 21-year-old son Komo Namba, “both bought by Kumataro years ago,”32 were the ones who came to the station to pick up the runaway children. Iku tried to persuade them to return home. Yoshi was willing, but Otome was afraid of being whipped; so Yoshi insisted that he would not go without her. Iku and Komo Namba defended themselves by claiming that selling children for $25 was not unusual in Japan, and that one meal a day was necessary to maintain their figures as acrobats.

The authorities in this dilemma decided to turn the case over to Sam Yoichi Shimizu, secretary at the Japanese consulate,33 and Ryusen (aka Tamezo) Takimoto34, a graduate student at the University of Chicago in 1912 and a community activist. Shimizu told the authorities that “he did not know that Namba had done anything he should not do.”35 It is unclear what the Japanese consulate actually did as follow-up, but we know that Namba had six other children training at his “school” (located at 1227 E. 71st Street) besides Yoshi and Otome.36 Kumataro’s “sons,” Kiyo and Kaichi, must have been among the other six children.

We do not know what convinced him to settle down in Chicago, but it was obviously a good place for him to raise his family. Since they were perpetually training several children, Kumataro and Iku must have acted as parents to these young performers.

Furthermore, Iku gave birth to George Tsune Namba in August 1913.37 In addition to their biological and “adopted” children, an actor by the name of Kori Namba lived with Kumataro at 1227 E 71st Street.38

It seems that the Namba troupe also had a sponsor to support them: Yasuo Nishi, a Japanese businessman who had an office in the People’s Gas Building (128 South Michigan Avenue) and was engaged in Chicago's rice business.39 Yasuo’s father, Kamenosuke Nishi, was known as a successful Chicago businessman in the early 1900s. He was the owner of Japanese trading company, the Hinode, located at 498 W. Madison and 3856 Cottage Grove Ave.,40 and later Nishi K. & Co. at 4024 Cottage Grove.41

Notes:

1. 1910 census.

2. The Buffalo Times, March 14, 1904.

3. Ibid.

4. World War I Registration.

5. The Omaha Daily News December 11, 1904.

6. Ibid.

7. The Topeka State Journal, January 25, 1904.

8. The Omaha Daily News December 11, 1904.

9. Nichibei Shuho, December 17, 1910.

10.World War I Registration.

11. Chicago Defender, March 21, 1914.

12. World War I Registration.

13. Daily Republican-Register, July 3, 1907.

14. Ibid.

15. Canada Incoming Passenger Lists.

16. New York Arriving Passenger & Crew List.

17. Washington Arriving and Departing Passenger List.

18. World War I Registration.

19. Ibid.

20. The San Francisco Examiner June 5, 1911.

21. The Durand Gazette, August 10, 1916.

22. The San Francisco Examiner June 5, 1911.

23. St. Joseph News-Press/Gazette, June 26, 1912.

24. Chicago Examiner, November 15, 1912; Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1912.

25. Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1912.

26. Ibid.

27. Ito, Shikago Nikkei Hyakunen-shi, page 251.

28. Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1912.

29. Chicago Examiner, November 15, 1912.

30. Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1912.

31. The Rock island Argus, November 16, 1912.

32. Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1912.

33. 1910 census.

34. Chicago Tribune, November 15, 1912.

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid.

37. Cook County Birth Certificate.

38. Chicago City Directory 1912 and 1913.

39. New York Nippo March 1, 1913.

40. 1900 City Directory.

41. 1906 City Directory.

© 2022 Takako Day