Many Japanese who emigrated to Mexico in the first half of the 20th century decided not only to settle in this country, they also acquired Mexican nationality. Juan Guillermo Fuse was one of them who considered “Mexico as his homeland” and brought his wife Kiyoko, from the same town where he was born, in the Gunma prefecture, with whom he had three Mexican daughters.

When the war between the United States and Japan began in December 1941, persecution broke out not only of Japanese immigrants but also of these citizens who were already Mexican. The Pacific War thus acquired a racial aspect when the United States considered anyone who had "Japanese blood" as its "enemies."

This racist vision acquired such virulence to the point that some North American military personnel considered that the war against Japan should not end until “that race” was exterminated. North American society and the press echoed this atmosphere of hatred against the Japanese and their descendants. For example, the Los Angeles Times published in its pages that “a viper is nevertheless a viper wherever the eggs are incubated,” referring to the children of immigrants. The measure of taking all American citizens of Japanese origin to concentration camps had high approval among the American population, prey to the hysteria and terror caused by the war and the propaganda about the “reptiles.” Nearly 80,000 American citizens of that origin, including children and young people, had to remain in 10 camps during the war, built quickly in the first months of 1942.

In Mexico, the government broke its diplomatic relations with Japan as a result of the attack on the North American naval base at Pearl Harbor and, in May of the following year, declared war. The government of President Manuel Ávila Camacho, since the breakdown of relations, issued orders to transfer immigrants living in the states of Baja California and Sonora to the center of the Republic with the purpose of keeping them away from the border, as had been done. demanded the American government. Subsequently, this order was extended to the entire country, so state and municipal authorities forced all Japanese and naturalized citizens of that origin to report in the cities of Guadalajara and Mexico to the Directorate of Political and Social Investigations ( DIPS), dependent on the Ministry of the Interior.

The municipal president of Chilapa de Álvarez, a small town in the state of Guerrero, was in charge of delivering a letter to Juan Guillermo Fuse, dated June 1942, ordering his “immediate” transfer to Mexico City. At first, Fuse and his family were surprised because Juan Guillermo had been a Mexican citizen since 1934 and had lived in Chilapa for eleven years. But Fuse was not the only one surprised because the authorities themselves knew his family perfectly and knew that Juan Guillermo was a Mexican citizen. In any case, both the local authorities and Fuse agreed that it was necessary for him to comply with that order and go to Mexico City to clarify his situation.

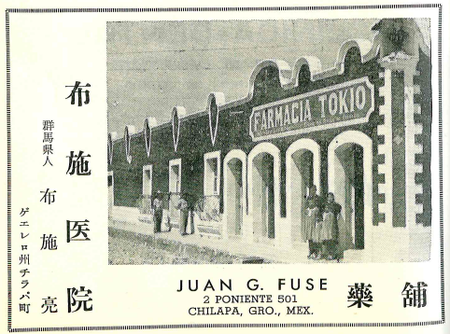

In reality, almost the entire population of Chilapa had had dealings with Fuse, not only because he had already lived there for years, nor because his two youngest daughters had been born in that town, but also because Juan Guillermo was recognized as a doctor in Chilapa, for what many residents had been treated by him.

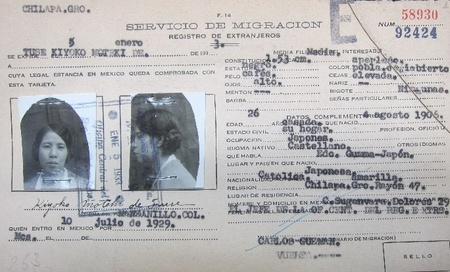

Fuse, at the time of the concentration, had been living in Mexico for more than 20 years since he had arrived from Japan in 1921 at the age of 26. We do not know how he moved to the state of Guerrero because there are records of his previous stay in Coscomatepec and Huatusco, both municipalities of Veracruz. Later he moved to San Marcos, a municipality located in the Costa Chica region of the state of Guerrero, where he would live for only one year when his wife had just arrived in 1929.

Chilapa was a very small town, with a population of 7,148 inhabitants according to the 1930 census. It was the entrance to the Mountain region, difficult to access due to its rugged territory with slopes and gorges. A large native population settled in this large region that spoke the Nahuatl, Tlapaneco and Mixtec languages.

We do not know the reason why Fuse decided to settle permanently in this town where he lived most of his life. It was probably influenced by the fact that his services as a practicing doctor, since he did not have a professional title, were considered indispensable and necessary by the people of Chilapeño. The entry into the country of a wave of Japanese professionals such as doctors, dentists or veterinarians was possible thanks to the fact that President Venustiano Carranza signed an agreement with Japan in 1917 that allowed the free exercise of these activities.

Accompanying the work of a practical doctor, Fuse opened a pharmacy where he prepared remedies and medications that helped the population cure their ailments and illnesses. Proof of his deep relationship with the population was the letter of support, dated July 26, 1939, where more than 100 residents of Chilapa stated that Juan Guillermo “has provided his medical services that are quite effective and economical, providing medicines at no cost when the "The patient is poor, so the population is grateful and happy with him."

Likewise, both the Agrarian Inspector of Guerrero and the Delegate of the National Peasant Confederation (CNC), stated, on behalf of the rural workers of the region, that Fuse's work was humanitarian because it served the most needy class. and therefore it was an extremely useful element for the working class.

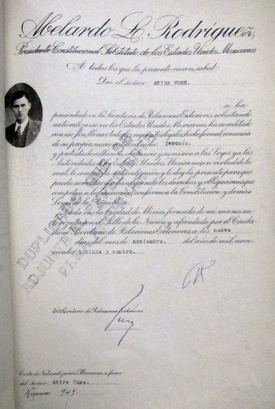

In Mexico City, Fuse reported to the Department of Social and Political Investigations and requested permission to settle on Guatemala Street #77, a measure that all Japanese had to take upon arrival in the capital. Juan Guillermo told the authorities that he was a naturalized Mexican and that he had renounced “all submission, obedience and fidelity to any foreign government” and that he had also “acquired the rights and obligations that apply to Mexicans in accordance with the Constitution and other laws.” ” as was proven in the naturalization letter that President Abelardo Rodriguez had signed in 1934.

In addition to pointing out this fact, Fuse requested permission from the head of the DIPS, Juan Lelo de Larrea, to return to Chilapa with the purpose that the governor of Guerrero would authorize him to continue residing in that state because despite his naturalization he was considered a citizen. Japanese.

In Guerrero, Fuse met with various local authorities to manage a series of letters and letters stating his good behavior and making it clear that there were no charges of any kind against him. On August 25, Juan Guillermo wrote another letter where he once again explained his situation to the Ministry of the Interior, mentioning his roots in the customs and thinking of the country and that both he and his family were Catholics. It also demonstrated that the civil and military authorities, members of the chamber of commerce and the general population gave evidence of his conduct, begging to be allowed to return to Chilapa. With the support of the authorities and the people of Chilapa, Fuse obtained authorization from the state governor, Gerardo Rafael Catalán Calvo, and the Secretary General of the Government, Ismael Andraca.

On August 31, he was allowed to return to Chilapa through an official letter signed by the head of the DIPS in the following terms: “Taking into consideration the broad guarantee granted by the Constitutional Governor of the State of Guerrero (…) authorization is granted to Mr. Juan Guillermo Fuse, of Japanese origin, nationalized as a Mexican (…) to live in the town of Chilapa Guerrero.”

Juan Guillermo and Kiyoko lived in Chilapa until the early 1980s when their daughters, who had studied in Mexico City, decided to take their parents with them due to their advanced age. In this town their professionalism and kindness are still remembered in the memory of those who knew them.

© 2021 Sergio Hernández Galindo, Araceli Wences Rangel