About a month after the atomic bombing, Kato Shinichi acted as an interpreter and guide for Dr. Marcel Junod, the chief representative of the Red Cross in Japan, who visited Hiroshima. On November 1, he was appointed chief of the political department, and in February of the following year, 1946, he was promoted to deputy chief editor of the Chugoku Shimbun as part of a restructuring of the company's internal structure following a change in president.

When I asked Kato's nephew, Junji Yoshida, what kind of activities Kato was involved in at this time, he told me that footage of him at the time can be seen on the Internet.

It was a 17-minute color video uploaded to YouTube, with no sound. The title of the video is " Hiroshima aftermath 1946 USAF Film ." It appears to have been filmed in April 1946.

A white man in priest-like robes and several Japanese children appear standing side by side in front of a destroyed building. Then we see people working in the fields among the rubble, new wooden temporary housing, Japanese people living there, and broken gravestones.

As the title suggests, it is a scene from Hiroshima after the atomic bombing. The next scene shows a woman in a kimono praying with her hands together. In front of her are what appear to be a mountain of small wooden boxes, each with a name or other information written on it. A man picks up one and hands it to the woman. It appears to be a box containing remains.

The boys are searching for something in the rubble, and in the background you can see the roof of a streetcar running through the destroyed city. A woman is placing flowers on a Buddha statue in the cemetery, two girls are dredging something up in the river, and a person is working on a utility pole.

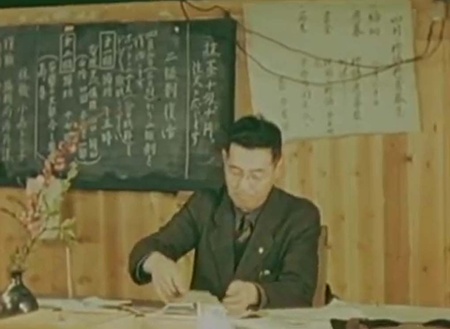

Kato in a suit editing

After this scene, the scene changes to a man wearing a hat and smoking a cigarette, holding a pencil and writing something that looks like a manuscript. The cover of Kinema Junpo can be seen on the desk.

After this, a man wearing glasses, a suit and a tie sits at a desk with his back to the blackboard, holding a piece of paper in his hand. A flower grows straight out of a vase in front of him. The man appears to be comparing the photo with the article, writing on the piece of paper with a dipped pen, and when he's done, he says something to the woman and hands it back. This man is Kato Shinichi.

It seems he works at a desk at a newspaper company. There is a badge, perhaps a company emblem, on his suit, and his hair is cropped short, making him look neat and smart.

This is the end of Kato's appearance, but what follows is what appears to be the editorial department of a newspaper, with several people working at their desks. They are dipping a brush in ink and drawing rectangular lines on paper, as if roughly laying out the pages. Next comes a scene of people picking up lead type. It's a sight that can no longer be seen these days, but in the past, newspaper letters were originally created by combining individual lead letters.

The video shows the process of searching for and "picking up" the type needed for an article, a process known as "text selection." The footage continues from this point on, capturing the process of creating a newspaper. The type collected for each article is arranged according to the text to create a single article block. These articles are then aligned to create a lead plate the same size as an actual newspaper page.

The next steps, which involve taking a paper template, using this to make a lead plate, and then using this to print the newspaper, are omitted, and the footage shows the press running, printing one newspaper after another, and a person checking the finished product. Meanwhile, for some reason, someone can be seen working at the desk where the Newsweek magazine is placed. Is the video trying to capture what overseas media also checks on a daily basis?

Looking at it this way, we can see that the purpose of the footage was to capture the process by which a newspaper is produced at the Chugoku Shimbun Company. However, there is something unnatural about the footage. For example, there is Kato's work. At the time, Kato held the important position of deputy editor-in-chief. The Chugoku Shimbun Company lost many employees in the atomic bombing, but the footage shows many other employees working. Therefore, in reality, it is unlikely that a deputy editor-in-chief would match a photograph with an article.

If you think about it like that, the flowers on the desk do seem a little ostentatious. The white men in priest's robes and the children who appear at the beginning of the film are too orderly and theatrical. I can't help but wonder if there was some kind of direction at work, but Kato himself later answered this question.

In his later years, he spoke on television

On July 7, 1981, 35 years after this footage was shot, the NHK Hiroshima station introduced the film showing the newspaper production process on their 6:40 pm program "Hiroshima 6:40." Kato, who was still alive at the time, was invited by NHK to talk about what happened at the time.

The Chugoku Shimbun newspaper on the day also featured this program under the headline "Headquarters Newspaper Production Scenes, Film Obtained by '10 Feet Movement', NHK Broadcasts Today with Related Parties." According to the article, the process of newspaper production at the Chugoku Shimbun at that time was filmed among the footage purchased by a citizens' movement called the "10 Feet Movement," which aims to make a documentary film using footage of the atomic bombing filmed by the U.S. military.

The program featured Kato talking about what happened at the time while the film footage was played, so it was unclear whether it was the same length as the YouTube video that Yoshida mentioned, but the filming location was the former headquarters of the Chugoku Shimbun, which was located in Ebisu-cho, Naka-ku, Hiroshima at the time, and the footage of the newspaper production process was the same.

Speaking about a man wearing a hat who appears in the program, Kato said, "This is Saeki Toshio, who was the head of the Economic Department," and when asked about the footage of himself editing, he calmly replied with a laugh, "That must be me, because I look very energetic."

Regarding the work itself, Kato said, "At the time, I was working in the news department as a sort of head reporter for the newspaper, so I didn't do things like collecting and organizing manuscripts like this." When asked, "So were you asked to do it?" he acknowledged, "The occupying forces came and I was asked to film the newspaper company's processes, so I guess I did it."

He also talked about the difficulties of making newspapers at that time, saying that they were flimsy because there was no paper.

Finally, when asked "How did you experience the atomic bomb as a newspaper reporter?" Kato mentioned his younger brother and sister who died in the bombing, and revealed that his sister had asked him to avenge them before he died. He powerfully stated, "I thought that my revenge was the war. That's why there must never be another war. As a living witness to the war, I have to tell the story as long as I live, and that's what I've been thinking." This was about seven months before he passed away.

(Titles omitted)

© 2021 Shinichi Kato