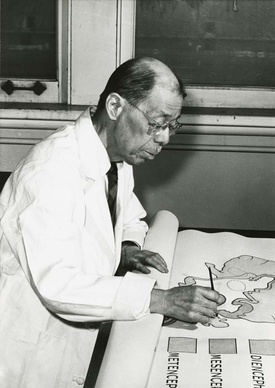

Not long ago I did a Discover Nikkei piece on the artist Bunji Tagawa, who made a career of scientific drawing for Scientific American, and who was lauded for the artistry of his technical work. I later discovered that Tagawa was preceded in the field by another prodigious Japanese artist-turned-scientific illustrator, Kenji Toda. Toda worked as staff artist in the Department of Zoology at the University of Chicago for 56 years, during which time he did thousands of drawings for zoology textbooks and biological works, and won international recognition for his work. His drawings ranged from endocrine glands as seen under a microscope to animals in their native habitat. He achieved further renown as a scholar of Asian art.

Kenji Toda was born in Japan, near Tokyo, on September 23, 1880. His father was Tadaatsu Toda, a travelling Presbyterian minister and missionary. The young Kenji was only 22 years old, and studying art at the Tokyo Academy, when he was invited to come to the United States and join the University of Chicago’s Department of Zoology as a staff artist. It is unknown how he came to be invited, but the University, though then only a decade old, was already attracting international attention as a scientific center. Toda accepted, as he later described it, “because I thought that I could earn enough money to study in Europe.” (He later reflected that he was thankful not to have carried out his European plans: “I would have been just another impressionist painter if I had gone.”) Once settled in Chicago, he began his work as a scientific artist.

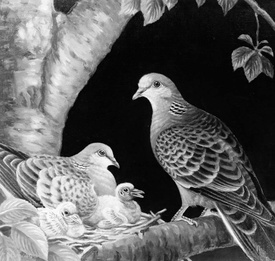

One of his first assignments was to illustrate a study of the evolution of pigeons that ultimately took form as Mary Putnam Blount’s monograph, The Early Development of the Pigeon’s Egg. It was the first of a long series of volumes that Toda proceeded to illustrate. In 1917, he contributed illustrations to Horatio Hackett Newman’s volume The Biology of Twins. In 1919 he provided halftones for Frank R. Lillie’s The Development of the Chick. In 1921, he did drawings for Charles Manning Child’s The Origin and Development of the Nervous System. Four years later, he provided designs for Warder Clyde Allee’s Animal Life and Social Growth. In addition, he contributed illustrations for technical journals. For example, he was engaged for many years with providing scientific designs for The Journal of Experimental Zoology. He also illustrated popular books such as W.C. Allee's The Social Life of Animals, as well as Allee and his wife Marjorie's book Jungle Island.

Apart from his work, Toda seems to have had few other interests. A Christian minister’s son who did not smoke or drink, and a lifelong bachelor, Toda seems not to have been a generally sociable man. Still, he was a member of the Chicago Japanese club in the 1910s, and served as chair of the Chicago YMCA’s Japanese department in the late 1920s.

Even as Toda worked at his day job at University of Chicago, he remained active as an artist outside. The 1920 census listed him as working as an art school instructor in Chicago. By the late 1920s, Toda gained recognition as an authority on Japanese art. He catalogued and annotated Japanese art collections at the New York Public Library, the Field Museum of Natural History and other places. His “Descriptive Catalogue” of Chinese and Japanese illustrated books at the Ryerson Library of the Art Institute of Chicago, published by Lakeside Press in 1931, was one of the first of its kind. It was selected by the American Institute of Graphic Arts as one of its “Fifty Books of the Year” and exhibited at the New York Public Library. (Two offshoots of the study had already appeared in the Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago, “Seventeenth Century Japanese Book Illustrations” and “The Picture Books of Nara”).

Toda’s work with the Ryerson’s collection led him to take in interest in Japanese scroll paintings, as he believed the main line of Japanese book illustration stemmed from them. In order to study the subject at close range, in 1932 he embarked on a yearlong trip abroad, touring Europe and then stopping in Japan, where he studied scroll painting at Tokyo’s Imperial Academy of Art. He was able to secure permission to view some of the small extent number of scroll paintings housed in Japan. Toda’s studies led to his book Japanese Scroll Painting, published by University of Chicago Press in 1935. It was made up of color plates of images, together with the author’s introduction on the history of scroll painting. The work was praised by The Chicago Tribune as “an exquisitely printed volume about the most exquisite of art mediums.”

A parallel project of Toda’s was the study of Chinese calligraphy. Joining forces with Lucy Driscoll, a professor of art at University of Chicago, he put together a study during the early 1930s based on ink rubbings from the collection of Berthold Laufer. When the work was finally published in 1935 by University of Chicago Press, under the title Chinese Calligraphy, it was widely and favorably received.

The New York Times critic Betty Drury led the praise: “In this striking and beautifully printed book, Lucy Driscoll and Kenji Toda set forth the Chinese attitude toward the art of calligraphy. The scope of their book is not historical, but attempts to summarize what Chinese authors have written on the subject.”

Nancy Lee Swann, librarian of the Gest Chinese Library (then at McGill University in Montreal) added in the Library Quarterly: “The vivid portrayal of the symbolism, of the dynamic ideal, and of certain values of calligraphic art are balanced with the presentation of the technique of calligraphic expression.”

In the period following Pearl Harbor, Kenji Toda remained employed at University of Chicago, even as the university turned away various Japanese American students and staffers. The fact that Toda used his Zoology Department chair as a reference on his 1942 draft card suggests that his Department bosses may have protected him. However, he seems not to have published work on Japan for a generation—perhaps he feared the appearance of disloyalty amid the nationalistic wartime climate.

Whatever the reason, it was not until 1954, when he was in his mid-70s, that he returned to the field with an essay in The Journal of World History, “The Effect of the First Great Impact of Western Culture in Japan.” The article examined the early introduction of Western pictorial art to Japan by Catholic missionaries in the 16th century, and its influence on the Japanese. Another article, “Japanese Screen Painting of the Ninth and Tenth Centuries,” which appeared in the journal Ars Orientalis in 1959, provided information on early Japanese art known as byobu-e. In 1961, he published another article in the same journal, “The Shitennōji Albums of Painted Fans.”

In 1958, five years after becoming an American citizen, Kenji Toda finally retired from the Zoology Department at the University of Chicago. He was then aged 78. While the official mandatory retirement age was 65, he had been permitted to keep working under a policy of “exceptional skills.” Following his retirement, he turned to working at the Art Institute of Chicago, helping compile and write descriptions for the Institute’s second volume of Japanese prints. Once that work was completed, he moved to Palo Alto, California.

In 1965, at the advanced age of 85, Kenji Toda published his last book, Japanese Painting: A Brief History, with the Charles Tuttle Press. It was a history of painting in Japan, composed of 36 black and white plates, with descriptions of art of the Buddhist, Japanese and Chinese schools. Writing in Journal of the American Oriental Society, Reviewer “E.D.S.” was not sparing in his criticism: “It is hard to see just what role the publishers expect this volume to play. It is questionable whether it will provide for the uninitiated a very coherent idea of the course Japanese painting has run. The initiated—for whom the book cannot be intended—will find a number of wayward conceits set forth.” Fernando G. Gutiérrez, writing in Monumenta Nipponica, was more charitable: “By way of popularization this gives a wealth of useful material for those who are making their first contact with Japanese painting.”

Kenji Toda died in Santa Clara, California, on March 14, 1976, at the age 95. His death was not marked by obituaries, neither in the mainstream press, nor even the Pacific Citizen. While his biography is little known, his books (thanks to later reprints) are still known and cited by scholars in the field.

© 2021 Greg Robinson