Editor’s note: Edwin “Bud” Nakasone served in the U.S. Army as an interpreter during the occupation of Japan in 1947-1948. Born and raised in Wahiawä, Hawai‘i, he witnessed the attack on Pearl Harbor, Wheeler Army Airfield and Schofield Barracks on Dec. 7, 1941. He is a retired colonel of the U.S. Army and an historian who has authored books and produced videos on World War II.

Graduating from the University of Minnesota, Nakasone became a long-time member of the history faculty of Century College, White Bear Lake, Minnesota. Currently at age 93, he has documented memories still clear in his mind. Here, Nakasone shares his personal experience in Occupied Japan as one of a wave of Nisei interpreters for the U.S. Army.

* * * * *

As a recent Leilehua High School graduate of 18 years old, I was eager to be drafted and go to Fort Snelling, Minnesota’s Military Intelligence ServiceLanguage School. On Aug. 10, 1945, just days before the war’s end, over 300 eligible Niseis were drafted. Soon we were on our way to training via the Army Transport Service ship.

Though most of the five days aboard I was seasick, the beautiful sight of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge brought swift recovery. And post haste we were on our way to Fort McClellan, Alabama, for basic training. During that time, the Allied forces’ victory over Japan ended World War II on Aug. 14, 1945.

After completing an arduous 13 weeks at Fort McClellan, we then boarded a train headed to Fort Snelling for our language-school training, arriving on Dec. 25, 1945. Hallelujah! Icy cold; snow and ice everywhere. Yet Minnesotans in general were warm, kind, gracious, and accepting of us niseis.

We started Japanese-language classes in March 1946. Since the war was over, the school curriculum had been changed drastically — the emphasis now towards civil, historical, cultural and most important, conversational terminology.

In July 1946, the language school’s location transferred to the Presidio of Monterey, California, when Fort Snelling was disestablished and retired fully as an army post. Our class graduated in early December, returned home to Hawai‘i for a two-week furlough and immediately shipped to Yokohama, Japan, via army sea transport — where I got seasick again on this 11-day journey.

Occupied Japan

My memories of Occupied Japan are vivid. We docked at Yokohama and others began flipping their lighted cigarettes from the deck. The emaciated, poorly clothed dockhands were soon scrambling to recover the precious cigarettes, which presumably might be later sold to others at high prices. Soon after, we were trucked to Camp Zama, the entry camp for newly arrived Occupation soldiers.

The entire metropolitan area was devastated; completely blasted, black, dark, burned out, not a building or house standing, as though a giant super-tornado had swept through the area. I noted bridge railings, metal downspouts that were all ravaged, ripped down to aid Japan’s war efforts. Camp Zama, Kanagawa Prefecture, was an old Japanese army camp taken over to house in-coming U.S. Army Occupation troops. I recall the many scantily clad Japanese youngsters hanging close to our mess-line garbage barrels and begging or sneaking a fistful of food from these garbage containers. It was a sad picture to see the once proud, courteous people struggling to eat in order to survive.

Tökyö Scene: My Assignment To 168th Language Detachment

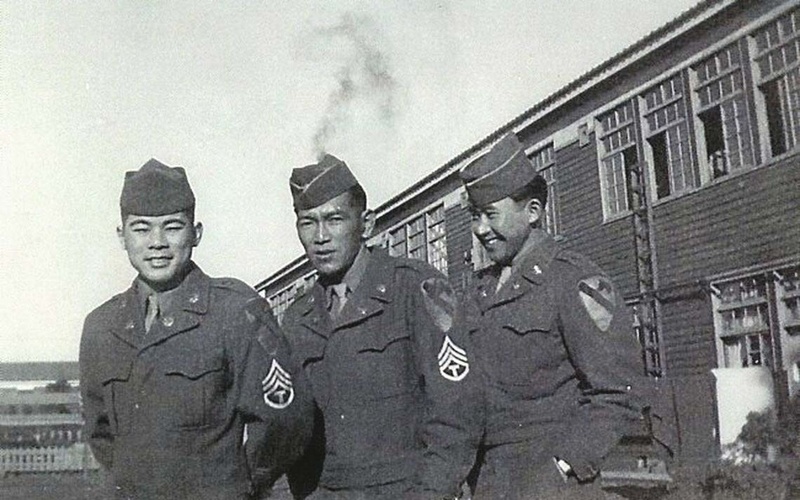

A week later we were transferred to the Nippon Yusen Kaisha, a seven-story brick building close to the Tökyö Central Railway Station, the Imperial Palace and plaza. This was the headquarters of Allied Translator and Interpreter Section, Gen. Douglas MacArthur's language headquarters. Here, we were all tested on our language prowess. Those who did not score highly were assigned to lower-language units of the Occupation forces. I was assigned to be an interpreter for the 168th Language Detachment of HQ, 1st Cavalry Division, commanded by 1st Lt. Wallace Amioka, another Hawai‘i Nisei. I served as an interpreter within this 11-man unit.

We were located close to Tökyö in Asaka town, Saitama Prefecture. I often accompanied MP Jeep patrols to cordon poor unfortunate local girls and women to the U.S. Army Medical Department's prophylactic stations. I hated this type of language duty. Other duties included general interpreting for officers of the 1st Cavalry Division HQ. The more proficient Kibei (U.S.-born Japanese Americans who returned home to the U.S. after receiving their education in Japan) linguists of our unit did court interpreting in Class C trials of Japanese wartime soldiers.

Court trials against Class A and B offenders were generally held in Tökyö Army headquarters.

The Tamanegi Syndrome

The regular tamanegi (round onion) event that saddened me occurred almost every day at Tökyö Central Railway Station. Often, Tökyö dwellers would fold their nice kimono into their furoshiki (carrying bag made of a cloth wrapping), then travel by train into the countryside. They would barter the beautiful kimono for rice and vegetables.

Tearfully, they returned to Tökyö, where the metropolitan police had set up a net and forced them to turn over the excess rice and vegetables; town dwellers were limited to a certain amount of vegetables. Yes, as though they had cut or peeled a tamanegi, survivors shed tears — having bartered their nice kimono for food in order to survive, only to come back and have them taken away.

Travel in Occupied Japan

As Nisei linguists we developed close associations with the Japanese. They often remarked how wonderful it was that we were in Japan as U.S. Army soldiers. We spoke Japanese; we understood the customs, emotions, history, and culture of Japan. We developed close relations with several Japanese families and took specially emblazoned “FOR ALLIED PERSONNEL ONLY” coaches free of charge. Grateful, we shared some of our canned rations that featured hamburger and pork and beans — the Japanese were starved for such delicacies. They reciprocated by providing us excellent Japanese rice and all types of vegetable okazu. We came to know and appreciate the difficult travails of the Occupation-era Nihonjins.

Filial Visits and Going Home

One of the more moving experiences that many Nisei soldiers appreciated were filial visits to known relatives in Japan. My obasan (aunt) wanted me to head to Okinawa and begin the paperwork to have her daughter (my cousin) return to Hawai‘i. In mid-1947, I was able to hop a flight going there and figured out her location. Then, I found a jeep to take us to the military-government headquarters in Naha where I attested that she was born in Hawai‘i, that she was my cousin and that she was thus a U.S. citizen and a Kibei. All the paperwork was approved and she happily returned to Hawai‘i. I went back, too, honorably discharged in July 1948.

*This article was originally published in the Hawai‘i Herald on September 18, 2020.

© 2020 Edwin Nakasone