Several scholars who have studied Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker movement have mentioned a Japanese guest named Kichi Harada who stayed at the Catholic Worker in New York city during the 1930s and 1940s. Yet no one has taken the time to look into who this woman was, and her life before she came to live at the Catholic Worker.

In a recent biography of Dorothy Day, the authors state that she was “an unmarried Japanese American woman” who “had been living a comfortable middle class-life in Manhattan,”1 which only gives us a vague idea about who she was. Drawing on material from several archives, I have tried to reconstitute her life. There are still many questions, especially about her life in Japan, that remain unanswered, but the documents that I have gathered give us a better idea of who she was and show that she had an extraordinary life that needs to be better known.

Kichi Harada was born in Japan, in the city of Ashikaga, around 1875. We don’t have information about her family, except that she had a brother named Sadasuke. In 1899, she graduated from what was later termed the “Meiji Women’s Seminary”—presumably the Meiji Women’s School, an institution established by the reverend Kumaji Kimura, a protestant minister who had studied in the United States.2 The headmaster of the school was Iwamoto Yoshiharu, a journalist and social reformer whose magazine Jogaku Zasshi3 promoted Victorian ideals of womanhood that stressed the importance of women’s (Christian) educatiom.4 It is important to understand that, at that time, women’s education was still something of a novelty in Japan, where a profound chauvinistic view of women had long hindered their access to a proper education.5 It was only in 1899, the year that Harada graduated, that it became mandatory for prefectures to open up middle-school education to women.6

Although she remained a Buddhist all her life, Kichi Harada seems to have subscribed to the conception that Japanese women needed to be exposed to western ideas. This led her to travel to the United States in order to pursue graduate studies at Columbia University. Her goal was to bring back the knowledge she acquired, and share it with other women.7. She sailed from Yokohama on April 17th 1909, arriving in San Francisco on May 3rd. The American contact she gave to the authorities was R. Arai from New York, presumably the famous silk merchant Ryoichiro Arai, who was known for his hospitality to Japanese students.8

Once enrolled at Columbia, Harada attended Teachers College, from which she graduated in 1913 with two Masters Degrees, one in Education and the other in Arts. This achievement made her one of the earliest Japanese women to be awarded a graduate degree from any American university.9 Surprisingly, after she graduated from Columbia, Harada decided to stay in the United Sates. Was it because she thought there would be more job opportunities in this country for a woman, or because of the political turmoil that consumed Japan at that time? Maybe it was a combination of both factors. It’s hard to tell. What we do know is that she won a James Buell scholarship from New York University, which allowed her to carry on her study of pedagogy.10

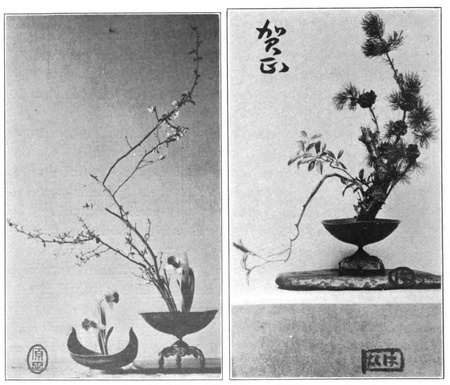

Meanwhile, Harada was engaged as a lecturer at Columbia, giving courses on Japanese art. Her specialty was Ikebana, the art of Japanese flower arrangement, which was gaining popularity among high-society women thanks in large part to Mary Averill, a rich New Yorker who had spent five years studying Ikebana in Japan. Averill’s book Japanese Flower Arrangement Applied to Western Needs, published in 1913, became a best-seller, and was reprinted three times in less than two years.11 Her second book, The Flower Art of Japan, was classified by the New York Times as one of the “Five Hundred Leading Books of The Season” in October 1915.12

Given this widespread interest in Ikebana, Harada had no problem finding an audience. In 1915 the artist and Columbia professor Arthur Wesley Dow asked her to come and give a talk before his class.13

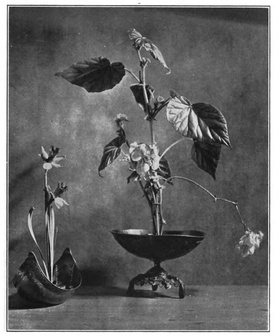

Some years later, Edward A. White, a professor of floriculture at Cornell, invited her to lecture, and used her work with accompanying pictures as a chapter of his book Principles of Flower Arrangement. In 1920, she taught Japanese Brush work and flower arrangement at the Commonwealth Art Colony in Boothbay Harbor, Maine. The following summer, modern photographer Clarence H. White and his assistant, the renowned Canadian photographer Margaret Watkins, asked Harada to demonstrate Ikebana to students in their photography classes.

In 1923, Vogue magazine published an article written by Harada, “The Fine Art of Japanese Flower Arrangement,” which explained the principles of Ikebana. In the early 1930s, she led classes in “study-hours for practical workers” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.Although Harada’s work was lauded by various important men, in the collective mind her art was categorized as something feminine, and her public was composed mostly of women. She was often hosted by women’s clubs to discuss Ikebana and tea ceremony.14

All those lectures allowed Harada to live a relatively comfortable life throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s. The 1920 census listed her as an art student, living as a lodger in the house of Toraji Kaimonji, a Japanese importer, at 168 Riverside Drive on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Unfortunately, in 1937, the Japanese invasion of China provoked a sudden increase of anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States.”15 Harada was deeply impacted by this situation: she stopped receiving invitations to give lectures. Her last one seems to have taken place in April 1938for the 45th anniversary of the Jamaica Women’s Club.16 After that she was totally marginalized.

Without money and people willing to help her, Harada was forced to live on the street. The Nisei writer Hisaye Yamamoto, who became a volunteer at the Catholic Worker after Harada’s death, recounted the story of Catholic Worker members finding her in the New York subway, where she had taken refuge. She seemed completely lost and frightened.17

They brought her to live with them at 115 Mott Street, on the Lower East Side, where they had their headquarters. Living at the Catholic Worker was a painful experience for Harada. Dorothy Day remembered that “her first reaction to Mott Street was one of horror”.18 Used to mingling with artists and high society women, she now had destitute men and women, those for whom her former companions would offer charity, as her everyday companions. Before losing everything, “she had been living on Riverside Drive, in sunny rooms looking out over a glorious river.”19 Those were replaced by “a miserable room in the slums, where one must make a constant fight against vermin, where one is surrounded by noise and the soot of many small factories that seep in the windows […].”20

Moreover, because she was Japanese, she faced racism from some people at the Catholic Worker. “She was insulted many times during the war, […] and there were those who told her after the bomb that the Japs deserved everything they got.”21 Against those people, “she argued, indefatigably in a high shrill trembling voice,”22 adding more noise to an environment where silence was a luxury.

Despite all those hardships, Harada also found a family at the Catholic Worker, among people who loved her and sought to make her life more comfortable. Yamamoto mentioned that, because “she required a certain amount of light and air and space […] she was given a room of her own upstairs, although this meant less space for the rest of the family.”23 Dorothy Day later recounted a memorable meal where Harada had “undertook to teach a few […] Japanese words for father and mother, for milk and bread and there was much gayety over the tender and funny words for mother and father”. This led Harada to say, “When a friend speaks even two words in one’s language, it relieves the loneliness of the heart.”24

Harada’s friends also tried to protect her from racist bigotry. Once Harada planned a Japanese dinner to celebrate December 3rd, the feast of St. Francis Xavier, which was the name day that the Catholic Workers had given her when she came to live with them. With others, she went to nearby Chinatown: “ to buy the necessary oriental vegetables, watercress, sauce, bamboo shoots[…].”25 When they came back from their shopping, they put everything in the kitchen and Harada went to her room to get an apron. While she was gone, a drunken woman “threw everything Kichi had bought on the floor, scattering it with a wide drunken sweep to the four corners of the kitchen floor, cursing out the ‘dirty Jap’ and her evident intent to poison [everyone].”26 This put Day in a state of “righteous rage”. After having sent the woman to her room, “she gathered up from the floor all the food and laid it out in plates for cooking, so that Kichi never knew how close to disaster her feast had come.”27

Harada remained at the Catholic Worker as a “guest” through the years of World War II, during which time she was relegated to a curfew and limitations on her freedom as an enemy alien. Her enemy alien status could explain why she chose not to publicly endorse the pacifist positions of the Catholic Worker. She didn’t want to attract the attention of the American authorities. Consequently, she never published anything in the paper. Although her name was mentioned in it a few times during the war, it was never in a way that would suggest that she held “subversive” ideas.

Kichi Harada died on September 13th 1946 at Columbus Hospital (later the Cabrini Medical Center) and was buried at the Rosehill Cemetery in Linden, New Jersey. When asked by the staff of the hospital what her religion was, she had this touching answer: “I’m nearer a Catholic than anything else.”28 Thus, we can say that, even if her life at the Catholic Worker was harsh at times, she was profoundly touched by her friends as they were also by her.

Notes:

1. John Loughery and Blythe Randolph, Dorothy Day: Dissenting Voice of the American Century, New York, Simon & Schuster, 2020, p.216.

2. Rumi Yasutake,Transnational Women's Activism: The Woman's Christian Temperance Union in Japan and Beyond, 1858-1920, Ph.D. Thesis (History), University of California, 1998, p.91-92.

3. Eleanor J. Hogan “Nogami Yaeko (1885-1985)” in Rebecca L. Copeland and Melek Ortabasi (Editors), The Modern Murasaki: Writing by Women of Meiji Japan, New York, Columbia University Press, 2006, p.294.

4. Michael C.Brownstein, “ Jogaku Zasshi and the Founding of Bungakukai,” Monumenta Nipponica, Automn 1980, vol 35, no3, p. 321.

5. Ibid.,p.320.

6. Rumi Yasutake, p.27. See footnote no33.

7. “An Exponent of Japanese Culture,” The Outlook, June 16 1920, p.312.

8. Daniel H. Inouye, Distant Islands: The Japanese American Community in New York City, 1876-1930s, Denver, University Press of Colorado, 2018, p. 207.

9. The first Japanese woman to obtain a graduate degree from an American University seems to have been Una Yone Yanagisawa, who was awarded the title of Doctor of Medicine in 1901 from the University of California.

10. Annual Catalogue New York University, New York, 1915-1916, p.588.

11. The Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), March 8, 1915, p.6.

12. The New York Times: Review of Books, October 10, 1915, p.382.

13. “Japanese Flower Art Illustrated in Talk,” Columbia Spectator, Friday, April 9, 1915, p.2.

14. The Courier-New s(Bridgewater, New Jersey), October 7, 1920, “Miss Kichi At Monday Club”, p.1

15. John Gripentrog, “Power and Culture: Japan’s Cultural Diplomacy in the United States, 1934–1940,” Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 84, No. 4 (Nov., 2015), p.510.

16. “Jamaica Club Presidents’ Day Features 45th Anniversary,” Times Union (Brooklyn), April 13, 1938, p.8A.

17. Hisaye Yamamoto, “Kichi Harada,” Pacific Citizen, December 20,1957, Section B, p.11.

18. Dorothy Day, “For These Dear Dead,” The Catholic Worker, November 1946, p.1.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid, p.1 et 2.

21. Ibid., p.2.

22. Ibid.

23. Yamamoto, op.cit.

24. Dorothy Day, “Day After Day,” The Catholic Worker, April 1943, p.2.

25. Julia Porcelli, “Story of Mary’s House,” The Catholic Worker, March 1942, p.5.

26. Day, “For These Dear Dead,” p.2.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid.

© 2021 Matthieu Langlois