Building on the foundations

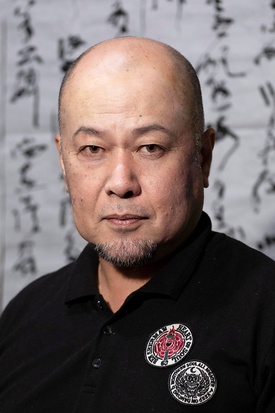

Fujii Yoshiyasu, who teaches calligraphy and has classes in Seattle, Washington, Portland, Los Angeles, and Tokyo, moved to the United States in 1989. He recalls that his purpose at the time was to be a bag carrier for his teacher, Akashi Shunpo, who was to teach at the University of Washington and the University of Michigan. In 1991, in response to a request to open a permanent classroom not only at universities but also in the United States, the Akashi Calligraphy School was opened in Seattle, and Fujii was put in charge of it. In the 30 years since, he has taught several thousand students in the United States.

However, he also experienced failure. When he first taught a calligraphy class for the University of Washington Extension Course, he was so concerned with how to keep the students engaged that he ended up teaching in a "popular" way, and as a result, the number of students dropped from 30 to just 12 after 10 lectures.

"I was still young at 27 at the time, so I thought that if I tried something new, they would accept it. However, I realized that I needed to build up a solid foundation, so I changed my approach the next quarter. I believe that my initial failure was extremely helpful in my teaching thereafter."

In addition to staying true to the basics when spreading calligraphy in America, Fujii keeps in mind above all else "teaching correct Japanese calligraphy."

"More than 30 years ago, when I saw American calligraphy, I got the impression that they had strayed from the basics and that it was like a show. To put it in perspective, it was like a musician performing classical music without studying the basics. They simply placed too much emphasis on expressing their own sensibilities in their work, and had become distant from pure Japanese culture. As a teacher, I wanted to properly teach kanji, which are the foundation of calligraphy."

In 1995, his master Akashi passed away in Japan. Fujii had the option of returning to Japan, but he decided to settle down and teach calligraphy in the United States, so he applied for a green card.

"Because my job involves Japanese culture, I applied and was granted the position under that category. It was the same category as the Russian ballerina (laughs)."

Although he did not withdraw from the university, he has students in Tokyo, so until the pandemic, he spent one week a month in Tokyo and the rest in Seattle. When asked about teaching during the pandemic, when face-to-face classes were not possible, he responded as follows:

"I sent them videos and exchanged messages with them through video chat as they were writing. I told them they could email their work whenever they wanted, so they would sometimes send it to me in the middle of the night, and I would have to wake up (with the notification sound) every time (laughs). Unlike the past, when instruction was impossible from a distance, we can now communicate thanks to technology like Zoom and FaceTime. As a result, I think we were able to minimize the number of students who dropped out because they were unable to come to class during the pandemic."

I want to breathe fresh air into Japan

Fujii has been traveling back and forth between Japan and the US for over 30 years, spreading the art of calligraphy. We asked him about the good points of each country.

"Regarding calligraphy, the good thing about America is that students don't have any preconceived notions about kanji and the like like in Japan, so they can start from scratch. Because they have no preconceptions, they learn quickly. And what I find great about American students is that they can truly rejoice with them in the achievements of other students. On the other hand, when I have suggested introducing good aspects of America to Japan, I have often been told that 'that's an American way of thinking and won't work in Japan.' So, since I turned 50 and have been allowed to serve as a judge for the (Mainichi) Calligraphy Exhibition, I feel that I have had more opportunities to speak out in Japan, little by little. In Japan, reform is sometimes seen as a bad thing, and in that respect I don't have a very good impression of Japan."

However, Fujii, who is soon in his 60s, says he plans to visit Japan more frequently once the pandemic is over, and to try to bring a breath of fresh air to the Japanese calligraphy world.

Next, we asked about their impressions of the Japanese community in Seattle.

"Thirty years ago, there were still Issei (first generation) people alive, and many Nisei (second generation) people active in society. In addition, there were many Japanese women who came to the United States to marry Americans. Traveling back and forth between Japan and America was not as easy as it is today, so people cooperated with each other. I also learned a lot about life in America from my seniors at that time. Speaking of which, once someone put the grass that was growing in our driveway in front of our door. I felt bad when I saw the grass pulled out and left there, but I later realized that the Japanese person who put it there wanted to teach us to keep the area in front of our house clean."

Finally, I asked him if he planned to obtain American citizenship in the future.

"Our two children were born in America and live in American society. Although my husband and I believe that even if we obtain American passports, we will still be Japanese, we will continue to cling to our (Japanese) nationality. I think it is important for us who come from Japan to continue teaching Japanese calligraphy in America. And we will convey the Japanese spirit through calligraphy. For example, when I leave the classroom, I bow towards the classroom. My students imitate me. They also line up their shoes neatly when entering the classroom. I am proud that my American students think that the spirit that begins with such a bow is beautiful."

He will not only teach calligraphy, but also convey the Japanese spirit to America and bring a breath of fresh air to Japan. I look forward to seeing more of Mr. Fujii's success.

The Meito Calligraphy Club website, run by Fujii: https://meitokai.net

© 2021 Keiko Fukuda