One of the more understudied topics in Japanese American political history is the presence of communists among Nisei intellectuals. Indeed, the late Asian American scholar and activist Yuji Ichioka called upon scholars to examine the complex network of Japanese American leftists among the immigrant communities. As with Robin Kelley’s book Hammer and Hoe that details the grassroots organization and activities of working-class black communists in Alabama during the 1930s, it is important to study the activities of the pro-communist faction that emerged among ethnic Japanese working in both Japan and the United States during this period.

Despite official efforts in the two countries to stigmatize communism, there was a long history of left-wing activities among Japanese immigrants. Dating back to the early 20th century presence of Sen Katayama (future founder of the Japanese Communist Party and member of Communist Party USA), there were a number of Japanese communists who exiled themselves from Japan during the Showa era in the United States, often joining forces with fellow Nisei (especially Kibei). New York-based Issei communist Jack Shirai was among the first American volunteers killed in the Spanish Civil War as a soldier in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion. Noted Nisei figures such as Karl Yoneda and Koji Ariyoshi pursued careers as labor activists and served in the U.S. military.

This article uncovers the pioneering work of Shuji Fujii, a Japanese American labor organizer and journalist. As one of the few outspoken labor journalists within the Japanese vernacular press, Fujii’s life story Is doubly revealing of the intellectual diversity of the Japanese American community and the treatment of communists during and after World War II.

Very few details exist on Fujii’s early life. Shuji Fujii was born on December 22, 1910 in Los Angeles, California, and as an infant went to Japan with his parents. After finishing two years of college in Japan, Fujii returned to the United States in February 1931, at age 20.

According to scholars Ronald Larson and Arthur Hansen’s interview with labor activist Karl Yoneda, Fujii left Japan because of the oppression of leftist groups by the militarist government in Japan following the invasion of Manchuria, though this seems doubtful as the invasion did not occur until September 1931. Upon returning to Los Angeles, Fujii finished two years of high school and took up a number of jobs in produce work.

In 1937, Fujii began work as the Japanese secretary for the Wholesale Produce Worker’s Union, an affiliate of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Rafu Shimpo English editor Togo Tanaka alleged that Fujii was ousted from the union for his radical views. Whatever the case, Fujii left the union and decided to begin a newspaper that would provide progressive opinions to the Japanese American community.

The result of Fujii’s work was the newspaper Doho. Its origins are uncertain. According to Karl Yoneda, following the collapse in 1936 of the San Francisco Rodo Shinbun, the Communist Party USA’s Japanese-language organ, he joined Fujii in establishing a new paper in Los Angeles. Its first issue appeared on January 1, 1937.

Although the journal's original title was Zenshin (“March Forward”), its editors offered readers a contest to submit a new name for the paper. Eventually the editors settled on the name Doho, or “Comrade.” A differing account is given by Togo Tanaka, who alleged that Fujii started Doho in the wake of the 1933 Mexican farmworker strikes against Japanese landowners, in order to appeal to Japanese American restaurant and produce workers.

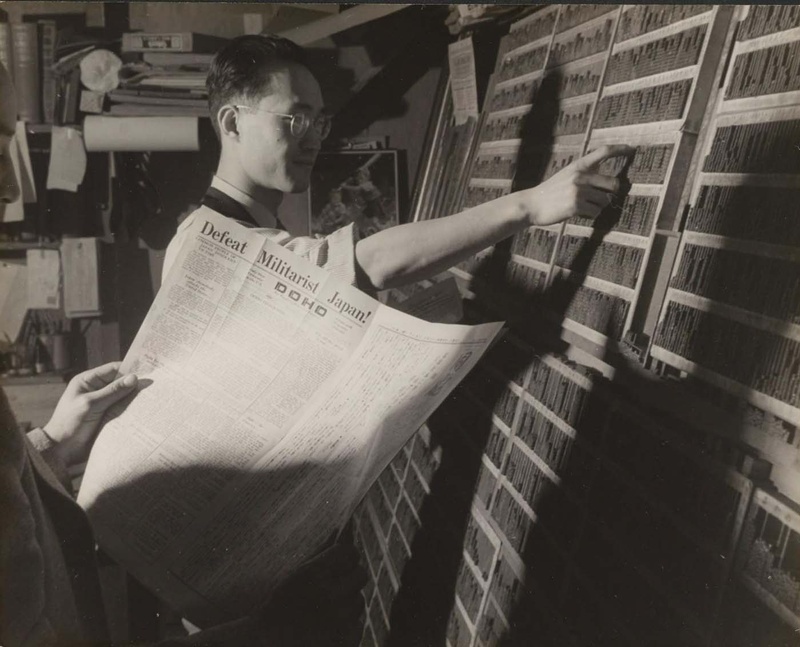

From 1937 until May 1942, when it was forced to close amid the mass incarceration of the West Coast Japanese community, Doho served as the voice of labor among the Japanese American community. It published bi-monthly or monthly issues, depending on the availability of funds. While originally an all-Japanese newspaper, it added an English page beginning in 1938. It boasted approximately 1000 subscribers – both among Japanese and white Americans – across the West Coast.

Although Doho never formally aligned with the Communist Party, and it received independent funding, Fujii and its staff, including leftist Kibei such as James Oda and George Ban, were all Party members. Historian Scott Kurashige describes Doho as part of a group of Los Angeles ethnic papers that supported the Communist Party-USA’s Popular Front agenda, along with the African American newspaper The California Eagle, which advocated for expanding the New Deal. Yoneda, who served as Doho’s Bay area correspondent, described Fujii as the “backbone of the paper,” who edited both the English and Japanese sections. Fujii’s wife Kikue, an accomplished writer and librarian from Oakland, also worked on the English section from 1940 on.

Labelling Doho a journal “for peace, equality, and progress,” Fujii printed articles related to local labor struggle and global political issues. For example, even as the Japanese vernacular press supported the Japanese invasion of China in 1937, Doho vehemently opposed it. Often Fujii’s columns connected fascism with economic exploitation, and he attacked together pro-Japan sympathizers and anti-union business leaders while calling for coalition-building among Los Angeles’s various ethnic communities. One of Fujii’s main subjects of derision was Sei Fujii (no relation), the owner of Kashu Mainichi, whom Doho criticized for his Japanese nationalism and for defending the Japanese occupation of China. An additional target of Fujii’s tirades was business leader Fred Tayama. Fujii accused Tayama of unfair labor practices such as paying workers at his Little Tokyo restaurant U.S. Café as little as $1 per day.

In response to Doho’s attacks, most Japanese community newspapers tried to discredit Fujii, labelling him as a defender of Moscow or an “aka,” (i.e. Red), a grave insult in the Japanese community. He had his defenders as well. For example, a letter writer in the April 27, 1941 issue of Rafu Shimpo praised Fujii for his courage in defending the loyalty of Nisei to the United States despite efforts of the Japanese government to indoctrinate them.

Although Fujii attacked JACL leaders such as Fred Tayama for unfair labor practices, he defended the organization’s American patriotism. When Senator Guy Gillette of Iowa and Korean nationalist Kilsoo Haan attempted to slander the JACL as a puppet of the Japanese government by using articles printed in Doho, Fujii swiftly corrected them.

Immediately following the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese military on December 7, 1941, Fujii began working nonstop to promote the U.S. war effort against Japan. Fujii released a “first wartime issue” of Doho within hours of learning about the attack, and encouraged Japanese Americans to pledge their loyalty to the United States. He sent a telegram to President Franklin Roosevelt on December 8th vouching for the loyalty of Japanese Americans to the United States. And when the JACL formed an Anti-Axis Committee, under the direction of his old adversary Fred Tayama, Fujii offered his collaboration. A number of articles in Doho instructed Japanese Americans to remain vigilant of sabotage and collaborate with the FBI.

In early 1942, Fujii joined journalist Larry Tajiri and artist Isamu Noguchi to organize the Nisei Writers and Artists Mobilization for Democracy. Fujii and Noguchi worked together on a series of reports on labor conditions within the Japanese American community which they submitted to government officials. Both engaged with writer Carey McWilliams and Congressman John Tolan regarding plans for resettlement, and submitted a statement to the Tolan Committee’s Los Angeles hearing.

Once the Western Defense Command announced plans for mass removal, Fujii joined the JACL in advocating collaboration with the government. Together with Noguchi and Wesley Oyama, Fujii assisted University of Southern California Film Professor Frank Judson in March 1942 in recording a film documenting the early movement of Japanese Americans to Manzanar and the construction of the camp by Nisei volunteers. The United Citizens Federation screened the footage to an audience of 2500 at Daishi Hall in Little Tokyo on April 6, 1942, with the goal of mobilizing further volunteers. Given this goal, the footage presented a rather more positive picture of removal than what later followed.

Shuji and Kikue Fujii reported to the WCCA’s Santa Anita Assembly Center in April 1942, and remained there until July 1942. While in camp, both engaged in organizing work. Because of his notoriety as a communist, Shuji found himself the target of conspiracies among groups of inmates. When Shuji learned that camp administrators had banned the production of a Japanese-language newspaper, he circulated a petition to permit its publication. In response, the FBI arrested Shuji on June 22, 1942, and sent him to the Los Angeles County Jail. Kikue, panicked by the arrest, wrote Noguchi, to ask his help.

The intervention of outside friends was decisive. On July 3, Shuji was released from prison, with the charges dismissed. Two weeks later, Shuji and Kikue left Santa Anita for New York in late July 1942, ending their three-month stay at Santa Anita and avoiding incarceration in one of the ten WRA camps. News of Shuji’s release from prison was reported by the Manzanar Free Press. In New York City, Shuji was hired for war work by the Office of War Information.

After arriving in New York, Shuji remained a steady correspondence with Isamu Noguchi. In his letters, Fujii expressed his frustration with the realities of camp, the JACL, and the lack of progress with the government regarding relocation. In mid-1943, with assistance from the antifascist group Japanese American Committee for democracy, Fujii revived Doho. However, operating from New York, Fujii found it difficult to connect with readers spread across the country, especially those in the WRA camps. Doho folded permanently in November 1943.

After a year of work, Fujii left the Office of War Information, and like fellow Nisei leftists such as Yoneda and Ariyoshi, began working for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). In late 1944, OSS sent Fujii and other translators to Calcutta, India as part of the propaganda campaign Operation Marigold, with Fujii as the operation’s leader. The OSS tasked Fujii with producing “black propaganda,” or misleading propaganda designed to deceive Japanese troops that they were produced by legitimate Japanese sources. As Howard Schonberger states in his article on Japanese American members of the OSS, Fujii argued with his superiors about the effectiveness of black propaganda, stating that Japanese soldiers could still determine their inauthenticity despite their being printed in Japanese.

After a brief stint in Calcutta, Fujii and a team of five translators went to Kumning, China on August 1, 1945 to set up operations for Marigold - only to receive news of Japan’s surrender two weeks later. Fujii eventually returned to New York City in September 1945. Following the end of the war, Shuji and Kikue Fujii remained in New York, where Shuji worked for the Japanese language newspaper Hokubei Shimpo. He enrolled in college classes at Columbia University, New York University, and Queens College, and worked as a freelance journalist. In January 1946, the Daily Worker listed Fujii as a speaker for The Jefferson School of Social Science, on issues related to the Far East.

As the McCarthy era dawned, Shuji’s past as a labor activist and communist attracted the attention of the government. In November 1952 the Pacific Citizen reported that a government agent, Paul Crouch, had testified before Congress that he worked with Fujii on Doho, in the process outing other Japanese Americans like Koji Ariyoshi and Karl Yoneda as Communist Party members. Ironically, although Doho’s political leanings were well-known to Japanese Americans and wartime government officials, Crouch’s notoriety as a paid witness for the Justice Department made his testimony suspect.

On April 25, 1956, Fujii testified before a Senate Committee investigating the presence of Soviet Activity in the United States. Fujii invoked his 5th Amendment rights when asked if by the committee if he was ever a Communist, and cited his war record as evidence of his loyalty to the United States. While he seems not to have been prosecuted, the anti-Communist hysteria nonetheless seems to have led him to maintain a low profile. He changed his name to Kyle, and pursued a career as an electrical engineer in New York City. Shortly after Kikue died in April 1978, Shuji Fujii died in June 1978.

Perhaps the last mention of Fujii’s long writing career appeared in the column of another famed journalist: Bill Hosokawa. In the August 25, 1978 issue of The Pacific Citizen, Hosokawa recounted his previous friendship with Kikue Fujii after receiving an envelope from Shujii’s attorney following his death. Hosokawa reminisced about his meeting Kikue, and wistfully stated “it turned out that Fujii and the other anti-militarists had been right all along.”

Fujii’s career, albeit somewhat brief, nonetheless left an impact on Japanese American political history. Fujii’s strong anti-Japan stance clouded his judgment regarding the incarceration, and led to his fervent support of forced removal despite the prominence of racism within the decision and the consequences facing the Japanese American community.

© 2021 Jonathan van Harmelen