Strings of origami cranes, circles of wish lanterns, maneki nekos and daruma figures—for decades I’ve watched my sister Teruko grow as an artist. I remember Teruko’s pencil sketches and charcoal drawings that our mother framed in our hallway to Teruko’s first solo show in Sacramento to public art installations in Texas, Mexico, and New York City. Though I’m four years older, I’ve always been in awe of her as an artist. She takes risks and confronts difficult themes, experiments with multiple media, devotes weeks of energy to a single repetitive task, and pours care into each of the hundreds of handmade objects that are a hallmark of her work.

She’s now living near our family in Tacoma, and we’ve begun to collaborate on projects like “Care Is Free” for Tacoma Arts Month. I’m excited to think about more collaborations in our future. I wanted to ask a bit more about some of the themes and currents through her work, and find out more about where her art is headed next.

* * * * *

Tamiko: Can you describe your early memories of making art?

Teruko: Most of my early memories of art making involve our family and their encouragement. My earliest vivid memory was a free exploration of mark making. I’m not sure how old I was but probably 3 or 4. I was lucky enough to be left alone with a whole pack of new markers, and I decided to try out each color on my body. Arms, legs, tummy, face - covered in ink! I think I enjoyed the tactile sensation of drawing on my own skin. When I was satisfied I walked out into the living room where Mom and Dad were sitting and triumphantly presented myself. Rather than scolding me for my actions they just burst out laughing.

My other strong memory of the practice of art making involves the “I’m bored bag” that you made me. I was often restless as a kid, and I was always making these announcements of how I was feeling - often it was “I’m Bored.” So to help me cope with that, as well as maybe shut me up a little, you made me pack an “I’m bored” bag which among other things, always included markers and paper.

Tamiko: Hooray for “I’m Bored” bags!—which I still have my kids make when we go on road trips. You’ve worked with different elements and themes of our shared Japanese American history, culture, and heritage in your artwork. Origami is a prominent element of your work, including cranes, flowers, and balloons. How do you think that’s evolved over your artistic career?

Teruko: When I first started using origami objects as a sculptural element, it was a way to enter into making something that felt personal and familiar. It was a comforting activity that connected me to my family and culture, and something that I could do that was different from most of my peers. It was also a starting point to making a three dimensional object as well as something which required an investment to learn technique and skill. It had this layer of meaning that I wanted to include and utilize to create form.

As I’ve continued to develop as an artist, the use of JA symbols and imagery has become more of an intentional act. I use them almost as a way to invite people to learn about their history and origins. For example, 1800 lucky cats or Care is Free and my upcoming Daruma installation in Austin - the meaning of maneki neko or daruma is wrapped up in the overall meaning of the work.

To enjoy the work to its fullest you must discover that background tidbit that makes my intentions more clear. I think that my aesthetic is also so influenced by our childhood home and our extended family’s homes who all had these collections of cultural artifacts - figurines, fans, dolls, beautiful dishes, etc. So it is also my sentimental associations and reverence for our history.

Tamiko: Discover Nikkei readers will also be interested to hear about the impact of our family’s Japanese history, based in Hiroshima, as well. Can you talk about how that has impacted your work through different phases and pieces?

Teruko: Going to visit our family in Hiroshima when I was 5 made a huge impact on me. It’s funny because I feel like it sort of just sits there in my unconscious mind all the time. Flashes of color, smells, sensations that float around my memory. It’s an early experience that sits very deep in my understanding of the world. Not only was it this sort of last major event we did as a family before dad died, but the actual visit to the Peace Park was a big eye-opener. It was the first time I realized a child could die.

The Sadako monument was kind of my entry point to public art and the power of monuments. It was also my first look at how art could be a focal point for community and participation (crane offerings). The horror of what I saw at the museum, but also the beauty of that little girl that looked like me as this powerful symbol of hope, that made a lasting impression that I still work through with my work.

The piece “For Every Sadako” is a response to that experience and an expression of my concern for all of the innocent victims of the many wars raging around the world. The work is a mirrored child sized coffin with origami cranes rising from it. The mirror is meant to reflect the viewer’s image to include them in the work. In that way it is an attempt to ask them to question their own possible role in the violence or ask them to think about how it might feel if their own child or loved one was treated as collateral damage.

Another recent piece that came from thinking about Hiroshima is my small installation “Hibakujumoku” or “survivor trees’. It is a Japanese term for trees that survived the atomic bomb. The gingko trees near the epicenter of the blast bloomed the year following the devastation, and that fact just really astounded and inspired me. The piece is a circle made of real gingko leaves and gingko leaves that I made from dried and stretched hog’s casings. It is meant to be a meditation on the precarious cycle of loss and redemption.

Tamiko: I love that piece, the Hibakujumoku. The negative space in the middle of the piece is also stunning, reminiscent of the flash of light of the atomic bomb—it reminds me that members of our family also survived that bombing, miraculously.

Repetition and scale are important features of your work…1800 lucky cats, 1000 cranes—can you talk a bit about that?

Teruko: As far as process goes, making something over and over again is a very calming and meditative act for me. Once I learn what form I want to work with, I love figuring out different systems of production, the puzzle of improving efficiency and time, the ritual of it, and then creating new tools or techniques - the challenge of endurance and the love shown through labor. But that sinking into the repetitive motions, with my hands busy, my mind is free to muse and contemplate and wander.

Aesthetically and conceptually, using multiples is a way of enjoying how many things can work together to make a collective whole, emphasizing the importance of many over the few. But at the same time, I also value the handmade, and the imperfections that are evident in individually made pieces, only obvious to the careful viewer, or the one who likes to look closer.

In terms of scale, I think I always think of it as a relationship to my body and my perspective, and in turn an imagining of the viewer’s experience. The placement of elements in my installations or the size that I make things is a part of how I hope people will interact with the work.

Tamiko: You’ve experimented with many different media and methods, rather than staying with just one. What helps you to decide the medium when you are creating a piece, or a series of pieces?

Teruko: It sort of depends on the piece, but I have come to appreciate how materials have meaning in and of themselves, and how that meaning can add layers and depth to what I am trying to express. For example, the gesture of making 1000 cranes is an action of tribute, respect, honor, hope. That labor and devotion becomes part of the piece like a foundation for a house or something.

Sometimes I am attracted to a tactile or visual quality, and it leads me on an exploratory tangent. Like when I was really interested in the concept of veils and translucency which brought me to light and shadows, rice paper to vellum, then drafting film, then silk and its properties. And then hog’s casings (seen in pieces like Hibakujumoku) that I stretched, dried and cured, and experimented with its structural and sculptural possibilities and its relationship to skin, and implications of death.

Tamiko: What are you working on next?

Teruko: Probably too many things... I have no shortage of things I am curious about. I tend to work on multiple methods and modes at once, spiraling around to all of my little workstations all over my studio and house - spending some time here, some time there. Nibbles of many things to satisfy all of my sensory taste buds.

Most recently I have been thinking about how the process of making an object or installation can be an important part of its meaning. So I have been making all of these videos documenting the action of making these sculptural works.

One piece I am working on for DORF gallery in Austin, TX later this year is about the trauma and prevalence of rape culture. It consists of pieces of wood I collected from walking the trails around my house that I then burned for firewood this winter. The uncured wood didn’t burn all the way, and the fire created these beautiful forms that are charred on some areas but still intact in others, like the bark and even moss still on it. I love how the black scarring emphasizes the growth rings in a very raw way, and the beauty of that scar. In an effort to talk about healing and the body the videos are of me polishing, sanding, and rubbing the scarred wood with wax and oil, and then the arrangement of those pieces and how they interact with one another - supporting each other, obscuring parts, or revealing others. I will display the videos and the final arrangement as relic of the action performed, an object whose life began much before what is finally seen.

I am also working on a series of sculptural textiles and wall hangings out of lanterns, silk, and miniature paper and wood barracks that I cannibalized from an earlier work for a show at Brooks Studio in Tacoma in 2023.

Tamiko: I’m so excited to have you here in the Pacific Northwest! Where can we see your work in the coming year?

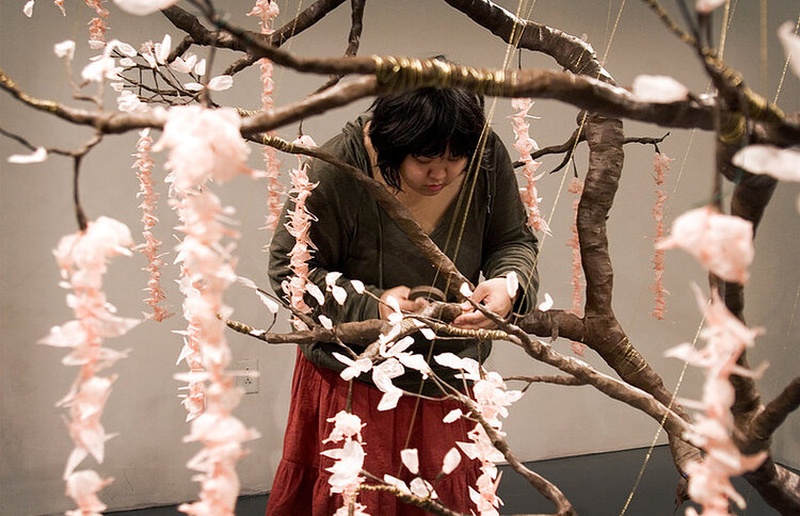

Teruko: I have two regional projects I am working on right now. The first is for the Bellwether Arts festival in Bellevue [Washington] in August. I was invited by artist and curator Priscilla Dobler to respond to the theme of growth with an emphasis on healing. My piece is a simple one about representation and Asian American presence. For Bellwether 2021 I will create Bloom, a life size figure constructed of strands of origami paper cranes. It will stand approximately 6 feet tall with a footprint of 6 to 8 feet in diameter. The cranes will be hung from a weighted wooden armature. Sculpted ceramic hands and feet will peek out from the drapes to emphasize the humble humanity of the cloaked figure. The piece is an assertion of Asian American presence. The tradition of folding origami cranes is a gesture of hope, fortune, and luck. Like many children of immigrants, this figure is carrying the aspirations of past generations. I think of the robes as many things: an armored garment of protection, a declaration of identity, and a veil that can obscure.

The second is in Tacoma as part of the Public Art Reaching Community Training Program with the city. I will be creating a large temporary installation in Wright Park in October that is about coming back together as people and community after the divisiveness and isolation of the last few years.

If you are in Austin in November I will be a part of a group exhibition at the Contemporary museum. The piece is about resilience and community and will be an installation of 300-500 hand made daruma inspired forms. Viewers are invited to take one of the talismans home as a gesture of solidarity and resolve.

© 2021 Tamiko Nimura