The Japanese attack on the North American naval base at Pearl Harbor in December 1941 unleashed a fierce confrontation between two of the most powerful armies in the Pacific. However, the war immediately generated hundreds of thousands of civilian victims who were displaced or sent to concentration camps in different countries in America. These populations were made up of Japanese immigrants but also their descendants who had the nationality of the countries where they lived and who, suddenly, were considered “enemies” for the mere fact of carrying “Japanese blood” in their veins.

The vast majority of Japanese descendants were young people and children who, despite not having the nationality of their parents, were considered part of a supposed “invasion army” of the Japanese imperial forces. In Mexico, one of those affected by the war and persecution was an eight-year-old boy who was born in Sonora and whom his parents, Zenzo and Fumie Tanaka, baptized with the name René.

The life of this family can clearly show us the conditions and ways in which immigrants arrived and integrated into Mexico and their situation before the outbreak of war. Let's pause a little on this aspect before continuing with the story of this child.

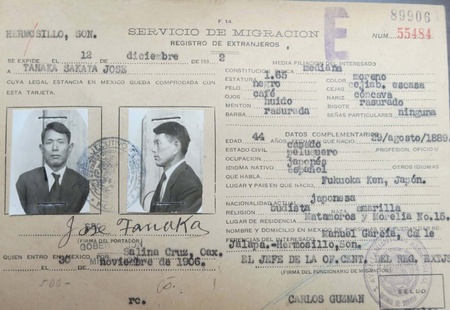

René's family had arrived in Mexico more than 30 years ago when the war broke out. His father, Zenzo Tanaka, was one of the first immigrants who sought better living and working conditions in Mexico that their country did not offer them. Zenzo, at 17 years of age, was hired in 1906 to work in a sugar mill, La Oaxaqueña, located in the south of the state of Veracruz.

The Japanese company Tairiku Imin Gaisha was the one who recruited, in the prefecture of Fukuoka, both Zenzo and his father and his brother. Tairiku and other companies of its type were in charge of recruiting the extensive, disciplined and cheap Japanese labor force to “export” it to various countries on the continent that required labor force to exploit the mineral and agricultural resources that North American and English companies produced in Latin America. Hundreds of thousands of impoverished immigrants arrived in waves since then to work in mining, agriculture, fishing and the construction of railroad lines.

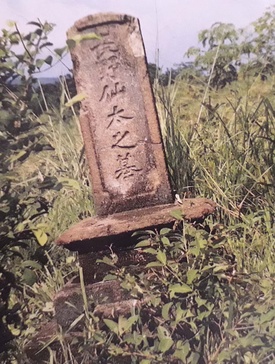

What the Japanese company had offered to the hundreds of Japanese workers in La Oaxaqueña did not correspond at all to reality. On the contrary, the deplorable and unhealthy working conditions caused dozens of workers to die from malaria or typhoid, as demonstrated by the carved stones of the tombstones with Japanese characters that are still preserved in that place today.

It did not take long then for the Tanakas and hundreds of Japanese to flee the La Oaxaqueña plantation. With the little money they had collected, Zenzo, his father and his uncle headed to northern Mexico in search of other work. Zenzo's father, disappointed, decided to return to Japan while the young man had various temporary jobs, since an important tool he had was that he knew how to read and write, a situation that allowed him to develop and learn various activities and trades. Swept up by the Revolution that broke out in 1910, he joined the ranks of the northwest army commanded by General Álvaro Obregón where he served as a stoker on the railroads that transported troops and later in the ranks of the army itself where he reached higher ranks.

In 1922, after 16 years in Mexico, Zenzo decided to settle permanently in the city of Hermosillo, Sonora, because the barbershop he had opened now allowed him to support a family. For this reason, he sent a personal photograph and a letter requesting a young woman from Fukuoka who would be willing to move to Mexico to marry him. In the port of Manzanillo, Zenzo would see 24-year-old Fumie for the first time, a young woman from whom he would never be separated throughout more than five decades of marriage.

In Hermosillo, Zenzo and Fumie were building a certain amount of capital that allowed them to have their first four children and send them to Japan, before the start of the war, with the intention of meeting their grandparents and for the eldest to enter high school. . The war would unfortunately abruptly separate the family.

At the end of the 1930s, René's parents decided to move to Ures, a town near Hermosillo. The move was due to the fact that a small community of immigrants lived there, who encouraged them to open a food and drink stand in the town's main square. René and his parents settled right next to the church where they rented a house with a central patio in which they had enough space to raise hens and chickens and even a Japanese-style bathroom, furo , which Zenzo built ingeniously.

Shortly before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, René was already attending primary school, there he learned to read and write the Spanish language. René, although he did not speak the Japanese language and communicated with his parents in Spanish, basically understood the language in which his parents and the Japanese community expressed themselves. In this small town, the boy not only learned to write his first letters but also, through his games and friends, acquired a close relationship with the country in which he was born and to distinguish what it meant to be the son of Japanese immigrants.

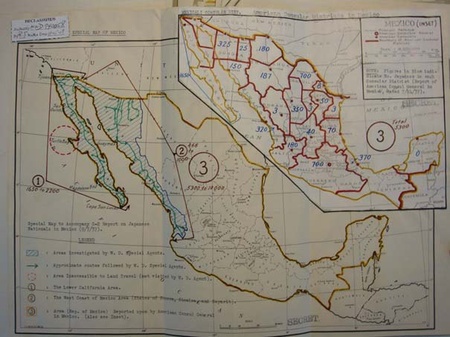

The icy winds of the winter of 1941 brought very bad news for René's family. The United States government requested the Mexican government to immediately transfer all Japanese immigrants and their families living on the border. The reason for such a request was that the North American government defined as a strategic military area the extensive area of the entire Pacific that encompassed not only the North American states from Washington to California but also the states of Baja California, Sonora and Sinaloa in Mexico.

The Mexican authorities ordered all families of Japanese origin to immediately gather in the cities of Guadalajara and Mexico in order to be closely monitored. Without understanding why he had to leave his home, abandon his school and get away from his friends, René, together with his parents, headed in the first days of January 1942 to the city of Guadalajara.

© 2021 Sergio Hernández Galindo