The Wakasa Killing

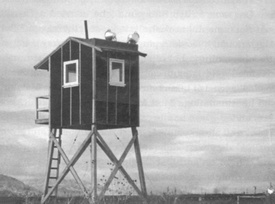

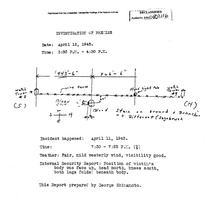

Guards had been regularly firing warning shots at Topaz residents when tragedy struck. On April 11, 1943, a military policeman shot and killed 63-year-old James Hatsuaki Wakasa, claiming that the elderly Issei was trying to escape. The autopsy, however, showed that Wakasa had been shot in the chest while facing the guard tower. News of the shooting was first covered in a one-page special issue in English and Japanese, on April 12, 1943, with a sympathetic statement from Topaz administration [officials] before running details of the shooting. In the article, it was reported that “while attempting to crawl through the west fence between sentry posts Nos. 8 and 9 at 7:30 p.m.,” Wakasa was “warned back four times by the sentries on duty,” and that when he failed to heed, was shot and instantly killed.

(Patricia Wakida 2014,2 describing how the killing was covered in the Topaz Times)

Tetsuden Kashima (2020) describes the shooting in an article on homicide in the Japanese American incarceration camps:

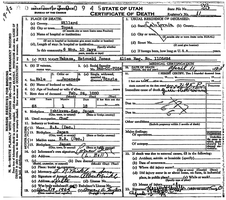

Before the April 11, 1943 shooting, the FBI reported that he had made two previous attempts “to leave the [Topaz WRA] center without a pass.” On that day at 7:30 pm he was shot by a military police sentry near the west fence and the U.S. State Department and the Spanish embassy sent representatives to investigate the homicide. They reported that the body was lying five feet inside the fence, and in such a way that he seemingly “had been facing the sentry tower and walking parallel to the fence; and the wind was from [his] back making it highly improbable that he could have heard [the sentry’s] challenge.” The Spanish official concluded that the incident was “due to the hastiness on the part of the sentry, who, not receiving an immediate response to his challenge, ‘probably fired too quickly.’” The army court-martial trial charged the sentry with manslaughter and then acquitted him.

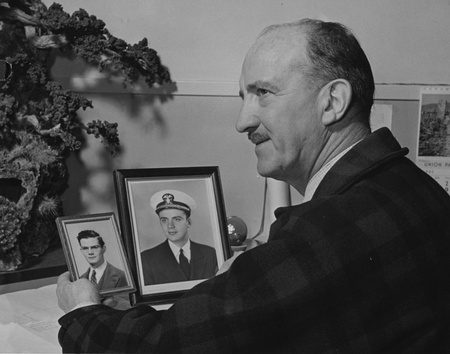

Nancy Ukai Russell’s 2020 Densho entry focuses on Mr. Wakasa himself, and succinctly describes the killing:

He was killed by a single bullet to the chest by a military sentry who later testified that the shot from the guard tower, some 300 yards away, was a warning. The military took the body away and no inquest was held. Believing that a riot might be imminent, the military put soldiers on emergency alert.

The most exhaustive account of the killing and its aftermath is found in Sandra C. Taylor’s Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz (1993: 136-147). Using a wide variety of sources, including official military reports, government archives, Topaz Community Council meeting minutes, Topaz Times articles, other newspaper coverage, published accounts, and interviews with former incarcerees, administration staff, and Delta residents, Taylor outlines the sequence of events from different perspectives.

At best, one could conclude that the shooting resulted from a very unfortunate combination of circumstances, ranging from ambiguity about the rules regarding the fence to the assigning of mentally unfit soldiers to sentry duty. But the immediate restrictions on the investigation of Mr. Wakasa’s death and the secrecy surrounding the court martial of the sentry can easily be interpreted as a cover-up, and emblematic of the racism and paranoia that drove the United States’ treatment of its Japanese American residents and citizens.

In her article, Patricia Wakida (2014) continues her description of the killing and how its aftermath was covered in the Topaz Times:

For seven consecutive days, the Times front page reported on the Wakasa death, including news that the MP sentry had been arrested and was to be court martialed, and on April 16, in a special issue, the WRA issued a statement assuring residents that they hoped no other similar circumstances would occur. The inmates demanded that they be allowed to hold the deceased man’s funeral on the spot where he was killed and that the WRA include Japanese American leaders in the investigation. When the WRA first denied these demands, the operations at Topaz ground to a halt, which was reported in the Topaz Times issue on April 22, 1943. While the coverage was ongoing, articles in the newspaper, such as Wakasa’s funeral that was eventually permitted or investigations of the shooting, were entirely devoid of opinion, and no letters to the editor or community voices were printed on this subject in the issues that followed.

The funeral was permitted not at the location of the shooting, but at an open area at the south end of the high school. The funeral was described in the April 20, 1943, issue of the Topaz Times:

Funeral Held for the Late J. Wakasa

Before a gathering of about 2,000 residents, the outdoor funeral service for the late James Hatsuaki Wakasa was held at the southern part of the high school area yesterday afternoon. With the opening of the Protestant funeral at 2:30 PM, the coffin was carried on to the platform, which was beautifully decorated with over 30 large wreaths and ornaments of artificial flowers. After the singing of a hymn, the congregation was led in prayer by Rev. J. Fujii. A scripture reading by Rev. I. Tanaka followed. At the conclusion of a biographical sketch of the deceased by S. Nakajima, a vocal solo was rendered by Kaoru Inouye. Introduced by Rev. M. Nishimura, who officiated at the ceremony, 5 residents, Tatsumi Watanabe, Masazo Ogawa, Shigeto Yamada, Taira Iwata and Frank Yamasaki, ceremoniously offered flowers to the deceased. Words of condolences were offered by Rev. Okayama in behalf of the Inter-Faith group, Aizo Takahashi, Tsune Baba, chairman of the Community Council, and James F. Hughes, assistant project director, in behalf of the appointed staff. Sermon given by Rev. E. Kawamorita was followed by expression of appreciation by Tatsumi Watanabe. The 2-1/2 hour funeral was ended with a benediction by Rev. H. Terasawa.

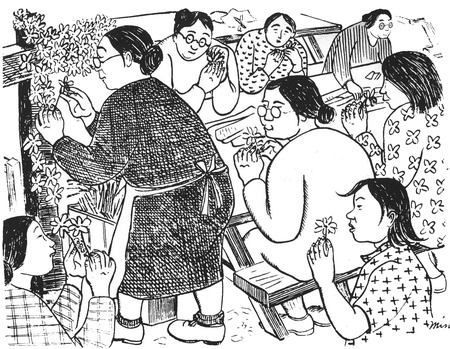

Jane Dusselier3 suggests that the large funeral wreaths noted in the Topaz Times article were symbols of protest as well as of grief:

Women of every block contributed time to creating “enormous” funeral wreaths made with paper flowers. In the context of Wakasa’s murder, these works of art were provocative and compelling visual forms of protest. Although these paper flowers spoke directly to experiences of loss and subjugation, the work of women crafters also encompassed acts of agency, an important juxtaposition since we often think of oppression and resistance in binary terms. As the actions of women making paper flowers for Wakasa’s funeral reminds us, oppression and resistance often reside together. More importantly, for at least some of the over eight thousand innocently incarcerated children, women, and men of Topaz, art created to mourn a truly unnecessary death likely provided both material and visual discourses of loss.

The Topaz Times reported that Mr. Wakasa had no known relatives and was a Christian. After the funeral Wakasa’s body was taken to Ogden to be cremated.4 The disposition of his remains is not known, but he may have been “laid to rest in the desert” (Uchida 1982:140). There was an area designated for a cemetery outside of Topaz, but no one is known to have been buried there.

Ukai writes that:

The Topaz Times and local papers printed the military’s claim that Wakasa was killed while going through the fence, but War Relocation Authority investigations established that the body lay several feet inside the fence and a postmortem examination found that the victim was facing the guard when he was shot. The accused, Private First Class Gerald Philpott, was found not guilty in a court-martial trial but the facts were “never satisfactorily disclosed to the residents,” wrote Miné Okubo in Citizen 13660.

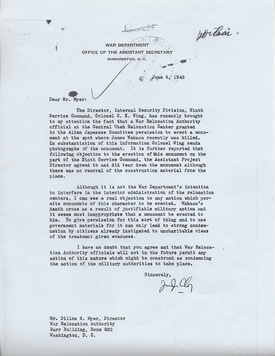

In June two members of the landscaping crew with the help of others built a monument where Wakasa was shot and killed,1 an act that was specifically forbidden by the camp administration. As Ukai notes, the monument created an uproar all the way to Washington, D.C. She shared with us copies of two letters found in the National Archives between the War Department and the War Relocation Authority. The first, dated June 8, 1943, was from Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy to Dillon S. Myer, Director of the War Relocation Authority.5 The monument’s existence had been reported to McCloy by the Director of the Internal Security Division, Ninth Service Command, Colonel C. K. Wing.6 In the letter, McCloy writes that he understands that the monument had been torn down at the direction of Topaz’s Assistant Project Director; nevertheless, he felt compelled to state:

Although it is not the War Department’s intention to interfere in the interior administration of the relocation centers, I can see a real objection to any action which permits monuments of this character to be erected. Wakasa’s death arose as a result of justifiable military action and it seems most inappropriate that a monument be erected to him…. I have no doubt that you agree and that War Relocation Authority officials will not in the future permit any action of this nature which might be construed as condemning the action of the military authorities to take place. [Emphasis added]

The second letter Ukai shared with us was from Topaz Project Director Charles F. Ernst to WRA Director Myer, in response to receiving a copy of McCloy’s letter. Ernst is quick to assure Myer that neither he nor his assistant authorized the monument, outlining its short history: a committee of ten Issei and five City Council members requested permission to erect a monument to Mr. Wakasa. Ernst refused.

When Ernst was in Washington, Assistant Project Director James Hughes wrote to him that two members of the landscape committee had constructed a monument at the site of the incident. Mr. Hughes accused the committee of breaking the agreement they had reached with Ernst (although there is no evidence the “agreement” was anything but a one-sided command). Hughes pressured the committee to have the monument removed, and Ernst concludes his letter to Myer reporting that “the monument has been torn down and the rocks which were used in this construction have been completely removed from sight.”

Although the military and the WRA held fast to the story that the shooting of Mr. Wakasa was justified, they did take steps to avoid further incidents. The administration restricted the military in their use of weapons and access to the relocation center. The military reassigned the guard who shot Mr. Wakasa. Nevertheless, a guard fired at a couple strolling too close to the fence a little more than a month later.6

Notes:

1. Sandra C. Taylor, Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz. University of California Press, Berkeley, 1993:143.

2. Patricia Wakida, Topaz Times (newspaper). Densho Encyclopedia.

3. Jane E. Dusselier, "Artful Identifications: Crafting Survival in Japanese American Concentration Camps." PhD Dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park, 2005.

4. Nancy Ukai, The Demolished Monument: James Hatsuaki Wakasa and the Erasure of Memory. 50 Objects/Stories: The American Japanese Incarceration. 1993.

5. John J. McCloy, Letter from John J. McCloy to Dillon S. Myer, June 8, 1943, James Hatsuki Wakasa Evacuee Case File, RG 210, National Archives, Washington, D.C., 1943

6. McCloy’s letter states that Colonel Wing also sent photographs of the monument, but the photographs have not yet been found (Nancy Ukai, personal communication to Jeff Burton, 2020).

7. Sandra C. Taylor, Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz. University of California Press, Berkeley, 1993:141.

*Editor’s note: Discover Nikkei is an archive of stories representing different communities, voices, and perspectives. The following article does not represent the views of Discover Nikkei and the Japanese American National Museum. Discover Nikkei publishes these stories as a way to share different perspectives expressed within the community.

© 2020 Mary M. Farrell; Jeff Burton