Modern Japanese overseas immigration began with 153 Japanese who arrived in Hawaii in 1868, as a result of an agreement between the Tokugawa Shogunate and the Kingdom of Hawaii. The Meiji government's new nation-building was a very ambitious endeavor, and it also focused on trade and industrial development. However, unfavorable treaties concluded before that created major obstacles to trade, for example, so no matter how much raw silk (silkworm industry) was exported, it could not be traded at a high price and could not be returned to the local Japanese economy as desired. In 1868, Japan's total population was 34 million, but it increased to about 44 million in 1900, 55 million in 1920, and 72 million in 1940. Although industry developed rapidly, it was not enough to provide prosperity to the growing population, and there is no doubt that the development of Hokkaido and overseas migration were one of the desirable options for people seeking a rich life.

In fact, Enomoto Takeaki, a former Shogunate official who served as foreign minister in the Meiji government, encouraged people to emigrate to Mexico. Some people also emigrated to Central and South America, either as groups or individually, in order to put to use the knowledge they had gained at agricultural universities and other institutions. Statistics show that just under 5% of Japan's total population emigrated overseas between 1868 and 1940. Of this number, 2.7 million people emigrated as colonists to islands in Asia and Oceania, including Taiwan, the Korean Peninsula, and Manchuria. Meanwhile, 230,000 people emigrated to Central and South America, and 320,000 to North America, accounting for 14% of all overseas emigrants.

During the war, many Japanese living overseas were subject to internment, relocation, or deportation, and after the war they were forced to make a major decision: whether to return to Japan or remain in their new home country. In the 1950s, mass migration took place to Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Bolivia, and Paraguay. Currently, there are 3 million Japanese descendants in the Americas alone.1

Before the war, about 5,000 people from Kagawa Prefecture emigrated overseas. The most common destinations were Brazil (2,100 people), Manchuria (929 people), America (810 people), Hawaii (158 people), and Peru (189 people). After the war, 630 people from 232 families emigrated overseas, with 403 people going to Brazil, 139 to Paraguay, and 37 people, including my parents, going to Argentina.

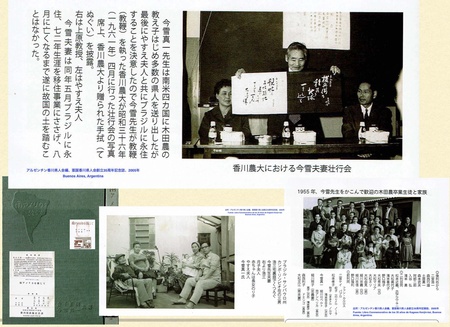

Looking at these immigrants, many were from Kagawa Prefectural Agricultural and Forestry School (now the Faculty of Agriculture at Kagawa University). This can be attributed to the guidance and influence of Professor Imayuki Shinichi, who taught at the school. In the school's garden, there is a bronze statue of Professor Imayuki Shinichi, who is described as "the foster father of the Kida Agricultural Colonization Department" and "the father of Kagawa Prefecture's immigrants to South America" 2 , and there is no one in the older generation of Kagawa Prefecture who emigrated to South America who does not know about Professor Imayuki3 .

Who is Professor Imayuki Shinichi?

Shinichi Konyuki was born in Kida County, Kagawa Prefecture in 1892. After graduating from Kagoshima Higher Agricultural and Forestry School, he became a teacher at Kagawa Prefectural Agricultural and Forestry School in 1919, and also served as principal. During this time, he visited Manchuria and the Southwestern Islands of the Pacific Ocean, and advocated the importance of overseas migration to many people, including his students.

After retiring, Imayuki founded the Kagawa Prefecture Emigration Association together with Governor Kaneko Masanori4 in 1953. In 1954, he spent about a year visiting Japanese settlements in four South American countries: Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Traveling from north to south and east to west, he spoke to 889 families and recorded the actual conditions and challenges of emigration in each country5 . He also arranged to meet whenever possible with state governors, government officials, and bureaucrats and experts in charge of agriculture and infrastructure.

According to Imayuki's third son, Kozo, Imayuki had promoted overseas migration as part of national policy before the war, but his one-year visit to South America significantly changed his views on overseas migration. Imayuki's four children also emigrated to Brazil and Paraguay, and Imayuki himself moved to Brazil with his wife in 1961, where he continued to provide agricultural and lifestyle guidance to his students and many fellow countrymen. He never returned home after that, and ended his life as a passionate educator in 1972, watched over by his third son, Kozo, and others.

There is much more to emigrating overseas than just determination and hard work, and he may have felt the many hardships that emigrants faced and the many unfair situations they faced. This is probably why he ultimately emigrated to South America and spent the rest of his life there.

A year-long visit to South America

We can learn about Imayuki's visit to South America from "Boumeiroku," a collection of conversations with his fellow countrymen, and "Records of an Inspection of South American Colonies," in which he records his sharp observations of the various colonies.

According to these notes, Imayuki's visit to South America began in the vastness of Brazil. He started in Suzano and Mogi da Cruz, suburbs of São Paulo where there are many strawberry cultivation and chicken farms, then he visited Registro, a green tea producing region in the southeast of São Paulo, Aliança settlement and Andoragina in the northwest of the state, Fujiwara fazenda (large-scale coffee farm), Mato Grosso state in the center, Pará state in the Amazonia region (Tome-assu settlement, Castanhár settlement, rubber plantations, etc.), Bella Vista colony in Amazonas state, Porto Velho and Treze de Setembre settlements in the federal state of Gapore (now Rondônia state), and he even took the train to the Bolivian border to visit Iyatsuta colony. It was not an era when you can fly in a single flight like today, so he traveled not only by train and bus, but also by horse-drawn carriage when necessary.

After that, he visited Argentina, where he visited several flower farms in the suburbs of Buenos Aires, mainly run by people from Kagawa Prefecture. After that, he also visited Mendoza (grape cultivation), which has delicious wine, the central province of Cordoba (ranches, wheat, and olive orchards), and the northeastern province of Misiones (mate tea cultivation). At the time, foreigners were limited to living within 100 kilometers of Buenos Aires, and within 50 kilometers of other cities, but the restrictions were gradually relaxed.

In Paraguay, he visits the La Colmena colony, which existed before the war, and learns that many immigrants have relocated to neighboring countries due to soil problems. He then visits the Chavez colony and the city of Encarnación along the Argentine border. He is impressed by Inoue's success in cultivating sweet potatoes in red soil.

The last country we visited was Uruguay, where we had a short stay of three days and two nights, during which we interviewed Japanese residents in detail, guided by the Japanese Embassy. At the time, there were 160 Japanese people living in 38 households, or 50 households including second-generation Japanese, most of whom were engaged in floriculture. As in Argentina, they noted that carnations, roses, and potted plants (ornamental plants) were cultivated, which was a distinctive feature of the country. Japanese people had made a major contribution to the development of the petal industry in both Argentina and Uruguay even before the war, and greenhouse-grown cut flowers were of good quality and had been highly profitable since those days.

Notes:

1. It is said that there are approximately 1.9 million people of Japanese descent in Brazil and 1.1 million in the United States.

2. " Kagawa University Newsletter ", No. 9, October 2011

3. The Kagawa Prefectural Board of Education has distributed a summary of Imayuki's achievements to schools in the prefecture as a moral education resource for junior high school students.

4. Mr. Kaneko, a former judge, became vice governor of Kagawa Prefecture in 1947. He was elected governor in 1950 and served in that position for six terms over 24 years. In recognition of his achievements, he was awarded the First Class Order of the Sacred Treasure in 1977. In 1980, he was awarded the title of honorary citizen of Kagawa Prefecture. He passed away in 1996 at the age of 89.

5. Details of his visit to South America can be found in "Hamakiroku," a compilation of interviews with migrant families, and "A Record of an Inspection of South American Colonies," a keenly observed account of the various colonies.

© 2021 Alberto J. Matsumoto