Along with my Issei father and ailing Nisei mother, I repatriated to war-torn Japan in 1946. We settled in my father’s domicile in Ehime Prefecture, Shikoku and initially lived in a three-mat room of my uncle’s small residence in Unomachi. Unomachi (now Seiyo City) was a landlocked mountainous town connected to the outside world by two tunnels, north and south. To the north lay Matsuyama, the prefectural capital; to the south, Uwajima, a port city on the southern tip of Shikoku. On the eastern flank was Kochi Prefecture and in the west lay Hokezu Toge, a mountain pass, and Uwa Kai, part of the Inland Sea (Seto Naikai).

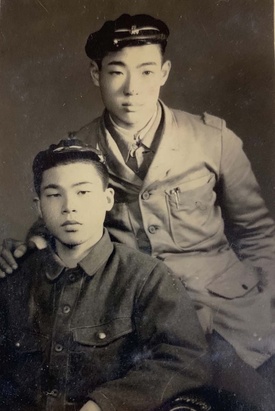

Jumping from the frying pan into the fire of postwar Japan, the first culture shock to visit me, besides the scarcity of food, was my uncle’s command to cut my hair. “Mittomo nai,” he declared. It’s ugly. I had the customary long hair worn since I was a child, but in Japan in those days the boys all had bozugari (shorn heads with 1/8th inch haircuts). I dutifully complied and was amazed at the transformation: I became an “instant” Japanese! I was transformed into an everyday, common Japanese kid.

As such, I entered Japanese school. I was initially placed in the fourth grade, but I figured that would put me too far behind since at thirteen I should have been in the first year of junior high, so I asked the teacher to bump me up to at least the sixth. But he put me in the fifth and that is where I began my Japanese schooling, basically ignorant of the language and customs, although I had gone to the Japanese school in Crystal City, Texas in preparation to coming to Japan.

On my first day at school, I nearly created a riot. The students all came flocking to the fourth grade classroom, gawking at the doors and windows, to look over that tall kid from America, standing head and shoulders above their teacher. He had come to class that day with his Made-in-America tablet and pencils. The items were passed around—and marveled at. “Gai da noo!” they exclaimed, using the local dialect to register their disbelief. The paper of the tablet was slick and did not have bits of straw in it, and the pencils had real lead, not the phony graphite that scratched holes in the paper like nails.

Kono Sensei, the fourth grade home teacher, was a diminutive man standing no taller than my chest and taught all the courses except history which was handled by Matsumoto Sensei who still wore his military uniform. He had repatriated from Manchuria. He gave me a “Shu” grade in history. I was fond of history, Japanese history, and studied hard. “Shu” was the equivalent of a B+ or A-. Otherwise, most of my grades were “Ryo” (B). I got only one “Ka” (C). That was in calligraphy. I didn’t know how to handle the brush…I kept holding it like a pencil, ready to write sideways.

The year I spent going to the Japanese school in Crystal City seemed to help me keep up my grades, although I couldn’t speak, read, or write the language well. The most I knew were katakana and hiragana and a few kanji, not enough to communicate. They spoke Shikoku-ben or dialect in Unomachi. In Tokyo, I had to relearn my Japanese all over again to converse in Edo-ben, standard Japanese.

The school building was a long corridor with classrooms. One had to take off your footwear at the steps after entering through the outside sliding doors to go to the classrooms. The corridor ran the length of the building. And each day after class, the students, armed with buckets of water and a padded hand-mop they provided, would mop their designated section by running up and down on all fours, producing a highly polished brown sheen. After such repeated mopping, the floor would be as slick and slippery as if it had been waxed with the finest substance.

During the winters, the students would shuffle their chilblain feet under their desks while they studied in the unheated rooms and suffer the cold with their layered coats on. Because of the shortage of all the essentials, few had any warm clothing and just suffered. I, too, fell into that category: I had outgrown all my clothes and depended on the ration of flimsy wear made of sufu (staple fiber) which fell apart after several washings. Footwear was also a problem: I had large feet and the tabi (split-toe stocking) did not fit and my heels painfully overhung the geta (wooden clogs). Wearing sashi-geta (stilted wooden clogs) in the snow was an adventure in itself. I stumbled often, much to the merriment of my classmates.

As winter turned into spring, the cherry blossoms in the hills would come out in profusion; the farmers would put up their grub hoes and the townspeople would close up their shops and retire to the mountains to spread out a mushiro (straw mat) under the cherry blossom trees and enjoy hanami. They would wine and dine and sing their country ballads and popular songs of the day, often to the accompaniment of a phonograph player. “Akai ringo ni kuchibiru tsukete…” (I press my lips to a red apple…) was all the rage in the years immediately following WWII. They would get to their feet and launch into an impromptu dance, singing, and imbibing.

Spring also included planting the school’s sweet potato crop. In a plot adjacent to the school grounds, we would ply our grub hoes (kuwa) and dig up a large section to prepare the soil for planting. The whole school would turn out. As the plants were growing and leafing out, we would have to weed the plot and apply fertilizer…which meant spreading night soil (human excrement) to the base of the plants. Lacking the appropriate footwear such as rubber boots, I performed the work in my bare feet with my pants legs rolled up as most of the other students did. We carried the night soil in two heavy wooden buckets, about five gallons each, suspended at either end of a yoke which was slung across the shoulders.

In spreading it, I unavoidably slopped the smelly excrement collected from the toilet pits of the nearby homes on my legs and attracted the slimy leeches to feed off of me. I tried to get rid of them by pulling on their slippery bodies but to no avail until an experienced farm boy showed me the proper method. First, you take a strand of straw used to cover the night soil in the buckets, flatten it, then slide it underneath the body of the leech and yank it and voila…the leech pops off. It always left a triangular bleeding wound, since that is how leeches penetrate the skin…through their triangular mouths.

Sweet potatoes were a staple in our diet. Rice and other cereal crops such as barley were rationed crops and sold to the government, so the nutritious sweet potatoes supplemented by various vegetables and an occasional piece of fish were our mainstay. We prepared them in a variety of ways. We boiled them whole, sliced them to fry, made dumplings out of sweet potato flour called kankoro.

Kankoro was made by slicing raw sweet potatoes thin, spreading the slices on a straw mat to dry in the sun until they were brittle chips, then breaking them up and grinding them into flour by a hand-powered usu, two grooved grinding stones with a hole in the top one to feed the chips (or grain) through. It was labor-intensive work but well worth the effort, for it resulted in a tasty dumpling that was steamed in a tiered bamboo basket with a slice of sweet potato filling. Needless to say, it wasn’t often that sweet potato dumplings made it to the dining table but when they did, they were consumed first of all—and quickly.

Otherwise, our diet was augmented by various vegetables (raw, cooked, or pickled [tsukemono]), fish and meat when available, and fruit such as persimmons and tangerines (iyo-kan) which were plentiful when in season. Sweets were few, but I remember buying packets of Morinaga caramels every so often. They were sweet enough, but I don’t know where they got the sugar in those days.

I added to our diet by shooting sparrows, fishing, and trapping eels in the Uwa River running the length of the landlocked mountainous valley. It cut its way along the floor of the branches of the valley and was probably what attracted the settlement of people there, so handy was it for irrigation, fishing, and watering livestock. It was where I fished and trapped eels and prepared them over a charcoal brazier called shichirin. I also shot sparrows with my pellet air rifle but missing more often than not. I was hard put to nail enough sparrows to make a meal. The only meaty part of the bird was its breast…after broiling, the tiny drumsticks were mere tantalizers.

The primary school was built in a U-shape pattern with buildings on three sides and a large playfield in the cup. A small shrine on a knoll sat at the opening. It was here that the school undokai (field day) took place. There were battles between the Ko (red) and Haku (white) teams in capturing the coveted flag. There were races with the men carrying full bales of rice. I remember, in a separate race, one junior high student running the 100 meter sprint in 10.2 seconds…close to the Olympic record for those days, I think. The housewives would prepare goodies to eat; shaved ice with azuki bean flavored syrup was served. An exhibit of handicrafts by the students was put on. All in all, it was a festive time for the townspeople who turned out in force as if the occasion were a holiday.

Finishing elementary school, I entered middle school at its multilevel building, newly built in the crotch of two mountains. But the postwar shortage of building material was evident in its windows which were made of wire mesh and a translucent cellophane-like covering. It let light in but one could not see outside to view the large elevated field lined by cherry trees and the roof tops of the houses. I was to spend the next three years in middle school in the new system of 6-3-3-4: six years primary school, three years middle school, three years high school, and four years of college, as revised by the Occupation authorities, which was more in keeping with the American educational system.

It was in middle school that I was recruited to play baseball. I came to Japan, bringing with me a Rawlings fielder’s glove, and that in itself, coupled with my physique, prompted the school to make me the pitcher as the baseball craze once again took over Japan. The end of the war awakened the baseball fever that had lain dormant for so long under the restrictive military rule. Now it burgeoned as the various leagues and teams began to organized anew.

Toward the end of my student days, I had occasion to meet and talk with Toyohiko Kagawa, the great American-educated Christian activist and reformer, who came to Unomachi once. I believe I met him on the strength that I was an American transplant, a repatriate. I don’t recall what I talked to him about, but it was brief. I may have mentioned my sick mother and her plight in war-torn, prostrated Japan, since she was my main concern in those days. She became ill in the concentration camps and never did recover. At any rate, my early schooling in Japan laid the groundwork for my understanding of all things Japanese, including the culture and history of the country and especially, later, its food. My fondness for sweet potatoes remains undiminished to this day.

© 2021 Robert Kono