“My mother had, throughout it all, kept a diary as many of her generation were doing; thus minute details, often easily forgotten, about specific events and names appear in her memoir.”

—Vancouver Author Grace Eiko Thomson

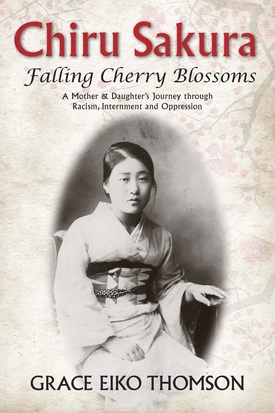

In an intriguing way, Chiru Sakura-Falling Cherry Blossoms: A Mother & Daughter’s Journey Through Racism, Internment and Oppression is an important book for these Covid times when we have more moments of idleness, perhaps, to contemplate upon where we have come from, where we might be for the moment, and where we might possibly be heading when, as the title of Grace Eiko Thomson’s autobiography suggests, these dire times have passed.

From Issei to Gosei and beyond, we are the creation of so many layers of history beginning even before our arrival in Canada, through ongoing systemic racism, colonialism, struggles to shed different constructs of Japanese Canadian that have been imposed upon us by the media, education systems, levels of government, etc. in order to find a truer sense of ourselves.

So, we’ve made it to 2021, in the midst of a global pandemic at that. If we use the marker of Manzo Nakano’s arrival in Victoria, BC in 1877, that’s 144 years of history. We JCs don’t get nearly enough opportunities to learn about ourselves as Japanese Canadians. Grace Eiko Thomson’s (nee Nishikihama) Chiru Sakura is a deeply personal memoir, a rarity from a Nisei who recalls a colourful life in Vancouver’s Paueru Gai, Japantown, in the ‘self-supporting’ community of Minto, on a sugar beet farm in Manitoba, and now back home again in Vancouver.

If you are lucky enough to know Grace as many of us do, you’ll surely agree that she is a rarity. Not only is she generous about sharing her experiences, she continues today to speak out and advocate for causes like Downtown Eastside issues in Vancouver, First Nations, and those directly related to JC history and identity. As far as active JCs go today, she is an elder whose voice still rings clear and true today.

So, to begin with, Grace is the child of parents Sawae Yamamoto (1913-2002) and father, Torasaburo Nishikihama (1902-1985) both of Miomura, Wakayama-ken.

The conceit of Chiru Sakura-Falling Cherry Blossoms is a back and forth conversation between Grace’s translation of her mother’s Japanese memoir, her personal reflection of those words, weaved together with her own compelling life story.

The Issei voice in the JC narrative is rare. Grace allows us to hear that voice through her translation which gives non-Japanese reading readers insight into the psyche of that first generation of immigrants to Canada, Issei, through a particular Nisei lens that is informed by a proud feminism, community activism, and fearlessness.

Her mother, Sawae’s (nee Yamamoto), voice begins the chapter entitled Paueru Gai, also known as Nihonmachi/Japantown, one of the places the Japanese first settled when they arrived in Vancouver. “On the 200 to 500 blocks of Powell and Alexander Streets, there was a variety of Japanese-owned stores. There were doctors, dentists and surgeons and the gynecologist, Dr. Chikao Horii, was well known. His office was at 736 Granville Street.” Ah, those formal, stiff, awkward looking sepia tone school class pictures offer a portal for readers, a step back in time.

The Japan where pre-WWll JCs came from was largely from poor, rural, coastal fishing villages. Like other immigrant groups today, our presence in Canada as a source of cheap labour was not particularly welcome: Newspaper headlines like the Vancouver Province (October 4th, 1932) were stirring the pot of hate with headlines like “One in Every 8 Babies born in BC in 1931 Is Japanese”. Further setting the context of our pre-WWll place, JCs were working in the nearby Hasting Mill in Vancouver and 222 Japanese Canadians (53 were killed) who had enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force that served overseas in WWl had been granted the franchise in 1931, a privilege that was not extended to their families. Life in Paueru Gai was bustling.

Grace points out that many Nisei tried to enlist into the Canadian army in WWll but were refused. (I only know of one who managed to enlist, Jack Nakamoto of Ottawa, who hitchhiked across Canada applying unsuccessfully at stops along the way to enlist until he got to Quebec.) JCs never refused to spill blood for Canada. However, it was not until WWll was coming to an end, at the behest of the British military under Admiral Mountbatten, first Earl Mountbatten of Burma, who requested that Japanese Canadians enlist as corporals to offer interpreting and translation services in Burma, that the Canadian government finally assented under pressure.”

Understanding the natsukashi, nostalgic feeling that the Issei and Nisei have for Paueru Gai, Grace explains, “For those leaving behind a poverty stricken Japan with great hopes, but finding in Canada that discrimination and unequal treatment were the norm, Paueru Gai became the new furusato (hometown), where immigrant families could live in relative peace.”

Minto Internment Camp and “Godfather” Etsuji Morii

“Although wealthy families were uprooted from their homes along with 22,000 others living on the west coast of British Columbia, a special consideration was made available to those willing to pay for transportation and rent. Self supporting sites were established in Lillooet, Bridge River, Minto, McGillivray Falls and Christina Lake (BC), and 1161 internees paid the government’s expenses for their own uprooting… most who moved to the self-supporting site of Minto brought with them all their personal belongings, including home furnishings.”

—Mother Sawae

I was intrigued to learn more about Etsuji Morii known as the “godfather” by some members of the community “since he owned a private gambling den in Vancouver, supported, we heard, by the local police.” Throughout the years I’ve heard that he headed a yakuza-type group with the ominous sounding name Black Dragon Society in Vancouver along with a judo dojo. He is said to have cooperated with the RCMP when there was the general roundup of JC community and religious leaders at the outset of WWll when were sent into prisoner of war camps. He is portrayed by Sawae as a more compassionate and kind man, perhaps mellowed by age and circumstance?

“... through their ability to pay rent and transportation costs, they were given the option to live in relative comfort… Their homes in Minto were largely homes recently vacated by middle-class miner families and the homes were of various sizes, with fenced in yards on established streets.”

Certainly, life in the ‘camps’ is remembered in ways that reflect the remembrances of the writers who pen them. It is important to remember, as Grace points out, that there were many monied and/or well connected JCs who did not suffer the deprivations of those living in the internment camps, sugar beet farms, and POW camps, whose stories remain largely unknown. Therefore, learning the names of Minto Mayor Bill Davidson, teachers Kazu Umemoto and George Tamaki and the colourful pictures that Grace paints of them reveals important aspects of a different kind of internment life that is not widely known.

Life in Middlechurch, Manitoba After WWll

After “internment”, we were “dispersed” (ah, so much softer than ‘imprisonment’ and ‘expulsion’), and the Nishikihama family went to Manitoba, Middlechurch (close to Winnipeg) to be exact, where the Ibuki story and her’s intersect as they worked on the same Mancer farm and Grace and my Dad went to the same school.

Sawae’s ruminations echo the feelings of many of her counterparts, “I often wonder now what people like Mr. Mancer, the farm owner, could have been thinking, or if they had any concern that we, a family of six with four young children, fellow human beings, Canadians (or did they not think of us as Canadians?) were treated in this way? The government called us ‘enemy aliens’.... Grace: “I remember Mother telling me that there were German prisoners of war working beside them, each wearing a shirt with a large red circle on the back, and that Father offered them cigarettes he had rolled.”

Yes, it is important to remember the 945 men who were sent by the government to ‘road camps’ in places like Blue River, Revelstoke, Hope (BC) and Schreiber and Black Spur (Ontario) and that so-called ‘dissidents’ (‘gambariya’), including members of the Nisei Mass Evacuation Group, were sent to POW camps in Ontario at Angler and Petawawa.

In a pattern that was repeated across Canada in the wake of the heinous “East of the Rockies” policy, the Nishikihama family moved to Winnipeg. “In Winnipeg, we were advised to ‘distribute’ ourselves among already existing neighbourhoods, often clusters of specific European ethnic communities that we quickly learned, carried their own memories of discrimination.” About 300 JC families lived in Winnipeg at the time. Similarly, JCs were being ‘encouraged’ to move to Edmonton, Calgary, Lethbridge, Toronto, Hamilton, Montreal, and others. Moving back to coastal BC was not an option until 1949.

Artful Living

Now, as a fearless octogenarian, Grace continues to be a force in Vancouver’s artistic community in the naming of our Japanese Canadian national museum, planting seeds in the wider community that will and have borne fruit (e.g. Hayashi |Studio doc) and continues to shape our national JC community as a former president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians (2008) and co-founder of Asian Heritage Month (May). In 1996, she became a founding Executive Director and Curator (2000) of the Japanese Canadian National Museum and curator of exhibitions: Re-shaping Memory, Owning History: Through the Lens of Japanese Canadian Redress; Shashin: Japanese Canadian Studio Photographers to 1942 and, Levelling the Playing Field: The Legacy of Vancouver Asahi Baseball Team.

Chiru Sakura reminds me dearly of where we have come from. Informed by the wisdom of her mother, this remarkable intergenerational, cross-cultural memoir speaks to a tumultuous period of our community’s history that offers an important message of hope to older and younger generations alike, just when we need it most.

* * * * *

Chiru Sakura-Falling Cherry Blossoms: A Mother and Daughter's Journey through Racism, Internment and Oppression by Grace Eiko Thomson (Caitlin Press, 2021, 200 pp., $24.95 (CDN), paperback) Caitlin-press.com.

© 2021 Norm Ibuki