I was orphaned in my 60’s. I do not have the luxury of that place Robert Frost describes: ‘Home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.’

I have created my own home. It is not a physical address.

When I wrote to my three younger siblings after our father’s death, observing that we are all orphans now, no one replied. To this day I am only in touch with my brother.

Since my son Jude’s death, I do not have living children for whom I am able to create that space.

Home is a turtle I found when I cleaned out Jude’s car—it is a tiny wooden green shape whose hard shell is reminiscent of Australian Aboriginal artwork. Its bobblehead reminds me of a compass frantically trying to find true north.

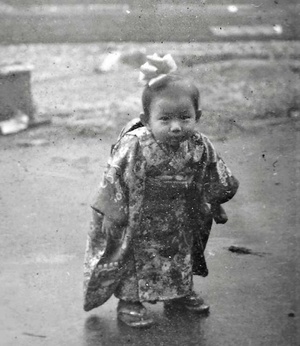

Home is a photo of me as a two year old brat somewhere outside my grandparents’ house in Kobe, decked out in full Japanese girl kimono, topped with a pink hair bow. I am bent at the waist yelling out ‘no!’ when my mother insisted I come in for a nap. For years I carefully carried a worn picture snapped of that moment, one of its corners creased and ragged. My husband, bless his heart, had it restored, enlarged, and framed for me on a birthday, or anniversary, or some other holiday.

Home is belonging to a community I have created around me for the past 40 years.

My name is my home.

Names are a basic form of identity, uniqueness, self. Naming a newborn is an important act of love, of belonging, of ensuring that the child is welcomed as part of the family. Some names are passed on from generation to generation, some names are made up, some are given a new twist in spelling.

In the sixth book of my Walkerville Desires series, Renaissance, my main character has a Japanese American mother and an unnamed Caucasian father.

She is named Topaz. This was her mother’s way of honoring the Relocation travesty of the World War II era. Executive Order 9066 of March 29, 1942 began the forced evacuation and detention of West Coast residents of Japanese American ancestry.

Four of her ancestors were sent to the relocation camp at Topaz, Utah. Three years later, only two returned to Walkerville. My character is called Paz and she confronts her mother about this name that is both a mystery and a burden to her. As a young child, she had two quests. One is her name’s origin, the other is her father’s identity. Her search is multi-layered, resulting in her leaving Walkerville for almost a decade, living her own life, making mistakes, making consequential decisions, and returning home with stronger resolve and a desire for answers.

In my family of origin, my father’s name was Yoshio and my name is Yoshimi. My mother’s name was Shigeko and my brother’s is Shigeru. I know my parents, or at least my mother put much thought into the names of her first two children.

My career Army father, with his ability to speak Japanese, was a translator in Kobe, Japan during the Occupation. It was there that he met my mother, born and bred in Kobe, who loved all things American. Her seamstress gift allowed her to see a dress or a suit and make up her own pattern, so she was always turned out in up-to-date fashion.

My father grew up in Wahiawa, Oahu. He said Scofield Barracks was spitting distance from his family farm. As the youngest in a family of four boys (with the oldest child being the only girl), my dad was pretty spoiled. He ran around cane and pineapple fields barefoot – he hated wearing shoes. One of my earliest memories is of Dad coming home from work, immediately taking off his work shoes and slipping into his zoris.

This wild Hawaiian boy met the sophisticated Kobe girl and they married and raised a total of four children. Only my brother and I received Japanese names at birth. My sisters, born years later, were given Anglicized names; their Japanese names were added as an afterthought.

When I was four years old, my parents, my brother, and I were transferred to San Antonio Texas. This was in the early 50’s—the Korean War was coming to an end. My father never joined us in San Antonio; he was sent to Austria. So, it was three of us in San Antonio Texas;an environment of unrestrained hatred for anyone whose skin was yellow, with slanted eyes and thick, straight, black hair.

A few days after our arrival, we were greeted by a group of Army men and their Asian born wives. The unofficial leader of this group was an older white woman. At this gathering, my mother was given the name Ziggy, I was to be called Jean, and my younger brother Kenny. It was explained to us that our given names were too hard to pronounce and these names were easier to say and would help us fit in better.

I have to say I never, ever felt like a Jean. I always looked over my shoulder when I was called that name. In my mid-20s I found myself in divorce court. The judge asked me what I wanted. I immediately declared that I wanted complete custody of my son and that I wanted my name back.

After a few minutes deliberation, he banged the gavel announcing, ‘Done!’

* * * * *

Fast forward several decades to the Fall of 2017.

I had written all my life, and at that time I had written my first women’s novel. I was exploring self-publishing. I was introduced to a successful Romance Writer who had been self-publishing for almost a decade. I was honored that a Real Writer was willing to give us (my husband is my publishing factotum) an hour of her time.

My first intuitive impression of RW (I’m calling her that for obvious reasons) was that she felt like a block of ice. I couldn’t feel any warmth from her. I felt like she really didn’t want to be doing this, that she had better things to do.

One of my quirks is when I feel this energy I respond in a fawning manner. I acted more grateful, more excited, more respectful; honored that she could eke out this hour recounting how she started out, what prompted her to write romances, and some advice about the self-publishing world as she saw it then, as an established author over the past 10 years. Yes, she loved the attention; my husband asked questions and took notes while I watched her fluff and strut.

Then, with smug assurance, she declared I would have to create a nom de plume. “No one will want to read books from someone whose name is so un-American,” she confided.

I died inside. I wanted to disappear. I wanted to disconnect from the three people in that room, one of them being my husband, my biggest supporter, and the person I trust the most.

With the shame of feeling intrinsically bad for wanting what I wanted, I disappeared. I could not hear the rest of the discussion. I felt no excitement, or joy, or curiosity. I made no eye contact with anyone in the room, although I felt my husband gently nudge me at some point.

Turns out my husband did catch that remark and, like me, decided he was going to move on; continue to get his questions answered. We could triage the situation later.

Which we did.

Coming out of my shame and the behavior that entails, I took action. I wanted to know if the advice to change my name was accurate. I wondered if Itruly even wanted to be a published author if that was the reality.

I wrote to a dozen writers, all of whom I had never met, asking about name changes to become a successful author. Two of them generously replied. The first person to respond identified herself as a ‘white woman with unusual first and last names.’ Her surname is French thanks to her ancestors, and her first name is unusual thanks to a mother who loved the holidays. She replied that the thought never occurred to her to change her name. She was born with this name; this was who she is. End of.

My second response came from a writer who, unbeknownst to me when I sent out my queries, was an Asian American who had changed her name. She honestly did not know if she would have had the same success if she had not done so.

I thought about the RW and her insistence I change my name. I often wonder how she would have responded if I had been Black, Hispanic? I wonder also if she meant to be racist or if she was truly trying to be supportive of a fledging new writer?

In all honesty, I have to say I spent about 48 hours thinking of ‘acceptable’ names. I did not change my name. And four years later, with my seventh book of a ten book series self-published, I am grateful I didn’t. I remained true to myself, I honor the name my mother gaveme.

Since COVID-19 the person occupying the White House before President Biden and Vice President Harris often referred to this pandemic as the ‘Chinese flu,’ ‘Kung flu,’ and worse. He drew a target on us by the color of our skin, not our names.

For the past year, around our country, Asian American activists have been reporting on the escalating violence towards AAPI individuals, many of them seniors. Mainstream media did not pick up on these stories until the Atlanta, Georgia March 28, 2021 shootings in which six of the eight victims were women of Asian descent.

NOW we were newsworthy.

* * * * *

As a young woman, I sometimes stayed home on December 7, Pearl Harbor Day. I understood the newsworthy importance of recounting the suffering and casualties perpetrated by the Japanese. However, because of the color of my skin and my name, I did not feel safe in public as a visibly Asian woman.

Many times, on that day I had been threatened. Men, usually white men, would breathe down my neck on the bus, in a hallway, as I exited a building alone. I was told to go back to ‘my own country.’ I was unwelcome in my home country.

I feared for my safety both emotionally and physically. I would call in sick, or not attend class. I just stayed safe.

When safety from COVID-19 dictated we shelter in place, I willingly complied. I found solace and exercise in my solo walks on local beaches. Now, since these attacks on elderly Asian-Americans, the prospect of a solitary walk brings fear, not comfort.

As a Japanese-American woman, I want to feel safe when I venture out of my home. I want to walk the beaches, the Fair Grounds, or the Ohlone Trail anytime I want.

We have created homes of brick and mortar. Many of us have created homes of the heart, whatever that means to us. These places are our refuge.

The homes we’ve created, whether physical houses or the people, places, mementos that live in our hearts; these places are no longer safe and welcoming. We become imprisoned if we continue to exist in fear rather than venturing into the world with curiosity and openness.

An endearing childhood memory was this short exchange as I left for school, “Ittekimasu!” (I’m leaving!)

Smiling, my mother would reply, “Itterasshai!” (Take care!)

Wrap me in a warm hug.

© 2021 yk miyazaki