Never Too Young to Learn Why We Should Always Strive for Peace

Last year, International Peace Day (Sept. 21) was observed just a few weeks after the 75th anniversary commemoration of the end of World War II. That milestone in history is one that we adults need to share with children. But, how can parents or teachers tell their school-age youngsters this important period in history without boring them with facts and figures and faded photographs? How can we help them understand why we should always choose peace over war and how, even in our own lives, we each can make a difference by trying to resolve conflicts peacefully?

With school-age children in mind, I recently read three books for young readers that impressed me with their message of peace: The Girl with the White Flag, about the Battle of Okinawa, by Tomoko Higa; The Complete Story of Sadako Sasaki and the Thousand Paper Cranes by Sue DiCicco and Masahiro Sasaki; and The Peace Tree from Hiroshima: The Little Bonsai with a Big Story by Sandra Moore.

Here is a walk-through of the books, each of which sells for under $15.

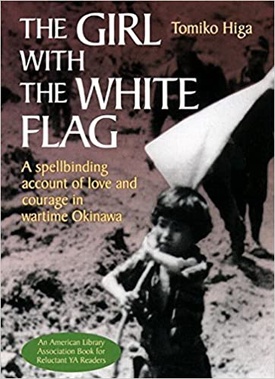

The Girl with the White Flag

By Tomiko Higa

Kodansha International published this 127-page book in 1991. I read it many years ago, but re-read it for this review. If you believe that war is about one nation emerging victorious over another, you need to read this book, because it will tell you who really suffers the most in war.

The Girl with the White Flag is author Tomiko (nee Matsukawa) Higa’s real-life story of wandering through the battlefields of southern Okinawa, searching for her older sisters in what historians have come to regard as the bloodiest battle of the Pacific War — the Battle of Okinawa. The siblings become separated while searching for their widowed father a few weeks into the battle, which began April 1, 1945, when American troops landed on Okinawa. He was forced to leave his four youngest children at home while retrieving livestock for food for Japanese imperial forces — a deal he had made to avoid being conscripted. The children never saw their father again.

The book reads like a journal. It is the horrific story of Tomiko, who is almost 7, as she is caught up in the battle, which lasted only 82 days, but left over 200,000 people dead — American and Japanese military personnel and Okinawan civilians, including Tomiko’s 9-year-old brother, Chokuyu. He is hit by a stray bullet as he and Tomiko, exhausted from walking, sleep sitting up, leaning against each other on a sandy beach with their backs against a big rock. Unable to give their brother a proper burial because they must flee from approaching soldiers, Tomiko and her sisters, Hatsuko, age 17, and Yoshiko, 13, bury Chokuyu in a shallow beachside grave, promising each other that they will return to the site after the war and take Chokuyu’s body home and give him a proper burial.

As they set out on the crowded road with other civilians, Tomiko reaches up and grabs hold of what she thinks is a piece of her sister’s clothing and hangs on to it tightly as they escape on foot. After a time, she looks up at her sister and finds that it was not her sister’s clothing that she had been holding on to, but rather that of a stranger. Tomiko immediately lets go of the clothing and begins her frantic search for her sisters.

Alone and with no idea of where she is in the wide-open field of battle, Tomiko wanders to and fro, calling out for her sisters at cave entrances. Fearing she will reveal the location of their hideout to the Americans, the Japanese soldiers, hiding in the overcrowded caves with Okinawan civilians, chase her away. Tomiko is even chased by a sword-wielding soldier.

With nothing to eat or drink, Tomiko scavenges the countryside for whatever she can find, oftentimes rummaging through the backpacks of dead soldiers lying in the roadside. She writes about finding a river lined with people with their faces in the water. Thinking they are drinking the water, she waits for them to leave before approaching the river. When they don’t move, she realizes that all of them are dead — soldiers, old men, even mothers with dead children on their backs. In fact, there are dead bodies strewn throughout the area.

“It was like an artist’s depiction of hell,” she writes. “There were people as far as the eye could see, and yet not the sound of a single human voice, for they were all dead.”

Tomiko finally finds a cave occupied by an elderly couple. They let her stay with them and the three quickly bond. “Grandma” is blind, and “Grandpa” has lost all of his limbs. Tomiko cares for them as if they were her own grandparents. At their age and with their disabilities, they know their time is short. But they are determined that Tomiko shall live.

“Tomiko, the most precious thing in this world is human life . . .,” Grandpa tells her.

A few days later, Tomiko sees the old couple hurriedly tearing some cloth from Grandpa’s white loincloth. They tie it to a tree branch that Tomiko retrieves for them, not knowing what they intend to do with it.

Earlier, they had heard an American Nisei speaking “funny Japanese,” (probably Military Intelligence Service soldiers) calling for the people to come out of the caves. Grandpa and Grandma give Tomiko the white flag, the international symbol of surrender, and order her to leave the cave.

Tomiko wants to remain with them, or have them surrender with her, but Grandpa orders her out. She finally relents and thanks them for allowing her to stay with them. She bows to them and then heads for the cave entrance. Grandpa reminds her to hold her flag high and straight.

After squeezing out of the cave entrance, she walks down the rocky path with other civilians and Japanese soldiers. The little girl with the white flag catches the eye of an American soldier, who snaps her picture, which became the book’s cover photo. A short time later Tomiko is reunited with her sisters. As they are transported to a refugee center, her thoughts are of “Grandpa” and “Grandma.”

While writing this book in the late 1980s, Tomiko Higa retraced her steps, guesstimating where she might have been based on physical landmarks she recalled and then matching those general recollections against official U.S. Army battle records. A map at the end of the book traces her probable footpath over the roughly three-week period that she was wandering about alone.

I think middle school students will find this book hard to put down once they start reading it. Yes, it’s gruesome, and the photos aren’t very good, but in Tomiko they will find an indomitable spirit and come to understand that the casualties of any war also include innocent children, women and elders caught between the warring sides.

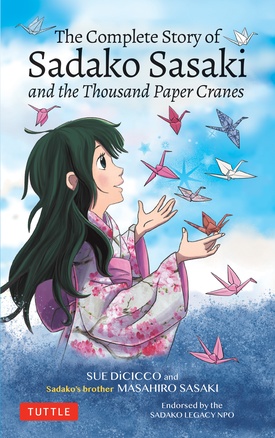

The Complete Story of Sadako Sasaki and the Thousand Paper Cranes

By Sue DiCicco and Masahiro Sasaki

Did you know that Sadako Sasaki was born in a pedicab en route to the home of her aunt, who was waiting to help bring Sadako into the world? And, did you know that the kanji character sada in Sadako’s name means “happiness”? Sadako loved Misora Hibari, one of Japan’s most famous singers and even saw her in person one day — did you know that? And, do you know why the Sadako-folded cranes that her older brother Masahiro (the book’s co-author) and his son, Yuji, donated to Hawai‘i’s World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument and the USS Missouri were so tiny — barely an inch wide? I now understand why, thanks to this 143-page book.

The title of this book from Tuttle Publishing says it all: It is the complete story of Sadako Sasaki, the courageous girl who died just 12 years into her life. Like most of you, I had read and heard Sadako’s story many times. But I always felt like I had walked into the middle of a movie on Sadako and her cranes. There was very little information on Sadako’s life before she fell ill with leukemia 10 years after the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945. Roughly 140,000 people died within four months of the bombing, either from the blast itself or their exposure to the radioactive fallout that blanketed the city after the bombing.

The book chronicles Sadako’s battle with leukemia, but also provides insight into her love for her family, and their love for her. We see her courage and, as her life nears its end, her desire that peace be her legacy and that it be represented with the paper cranes she folded.

The Complete Story of Sadako Sasaki and the Thousand Paper Cranes is told in a way that will keep readers of any age continuing to turn the pages. It’s probably most appropriate for fourth- or fifth-graders. Authors Sue DiCicco and Masahiro Sasaki thoughtfully included shaded boxes containing brief explanations of Japanese and English terms or concepts that may be unfamiliar to the reader — phrases such as ihai, the Japanese memorial tablet bearing the deceased family member’s name that is placed next to the Buddhist altar in the home; or pikadon, meaning “atomic bomb disease”; or “Mukö sangen ryödonari,” which, roughly translated, means, “Be a good neighbor.”

DiCicco, a former Disney animator, also illustrated the book’s eye-catching black-and-white manga-style illustrations. The book also includes photographs of the Sasaki family and a crane-folding activity for readers at the end. DiCicco’s line drawings of origami cranes are a visual theme throughout the book and are used effectively.

In the book, Jonathan Granoff, president of the Global Security Institute, makes a good point about the importance of the crane: “When children make a crane it gives them a personal connection to a tragedy that they might otherwise not grasp because its horrific dimensions surpass normal imagination. Focusing on one person’s story opens the possibility of becoming engaged in the abolition of nuclear weapons.”

Sadako Sasaki would have agreed wholeheartedly. Proceeds from the book will benefit The Sadako Legacy NPO and DiCicco’s The Peace Crane Project.

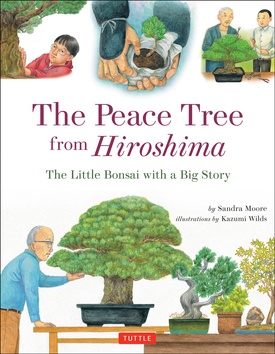

The Peace Tree from Hiroshima: The Little Bonsai with a Big Story

By Sandra Moore

The Peace Tree from Hiroshima, which Tuttle Publishing released in 2015, chronicles a white pine bonsai tree’s life in Japan over many generations and how it came to live in America. This book is probably a good read for second- or third-graders.

When this white pine was just a sapling, it was uprooted by bonsai master Itaro Yamaki in the mountains of Miyajima, a small island in Hiroshima Bay. Itaro-san carefully replanted the little pine at his home in Hiroshima and named his new tree for its birthplace, Miyajima. When Itaro-san grew old and passed away, his son Wajiro took over caring for Miyajima, and then his son, Somegoro, and so on and so on. For over three centuries, the Yamaki family nurtured Miyajima with tender loving care, raising the once-little pine into a healthy bonsai plant.

Then came Aug. 6, 1945. The world’s first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, claiming tens of thousands of lives. Interestingly, nowhere in the book’s 32 pages is there any mention of who dropped the bomb on Hiroshima, nor the second over Nagasaki three days later. Moore seemed determined to keep the book’s focus on peace and reconciliation.

The Yamaki family and Miyajima and their other bonsai plants survive the bombing and continue to grow as Hiroshima rebuilds after the war. Miyajima grows into a healthy and beautiful bonsai tree.

And then in 1976, America celebrated its bicentennial, the 200th anniversary of its founding as a nation. As a gesture of peace and friendship between the two once-bitter enemies, Miyajima — “the peace tree” — and 52 other bonsai plants from Japan were donated to the National Arboretum in Washington, D.C., which thousands of people visit annually.

When author Sandra Moore, a former journalist and U.S. Senate aide who lives in D.C., learned about Miyajima’s long journey to America, she decided to share the story in a children’s book to celebrate and promote the peace and friendship that has existed between the United States and Japan since the end of World War II.

Kazumi Wilds’ beautiful illustrations are simple, yet detailed and perfect for this book. Wilds now lives in America, but her memories of growing up in Japan come through in her illustrations. They also reflect the passage of time in Japanese architecture, clothing, hairstyle, and facial expressions.

Moore also includes a short glossary and pronouncer of terms that a young reader may not be familiar with — words like arboretum and kodomotachi and macaque. There are also some basic facts about the ancient art of bonsai.

Not surprising, the takeaway message of all three books is the need to work for peace, because the human toll of war is too, too great. Seventy-five years after Okinawa, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that message still rings true.

*This article was originally published by The Hawai‘i Herald on September 18, 2020.

© 2021 Karleen Chinen