From "History of Emigration to Hiroshima Prefecture"

As mentioned last time , Hiroshima Prefecture, where Kato Shinichi was born, was an "immigration prefecture" that sent out the largest number of people overseas during the Meiji period.

Looking at the number of immigrants nationwide, we can see that there are large differences between prefectures. As someone from Kanagawa Prefecture, I was not familiar with overseas immigration, and none of my relatives or neighbors had gone overseas. However, while reporting in Hiroshima, I found that it was not at all uncommon for relatives or acquaintances to have gone overseas, or for their descendants to be there.

So why did so many Okinawans leave the prefecture to go overseas? What on earth is the background to this?

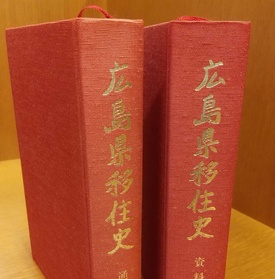

I had seen several reasons in immigration-related materials, such as the fact that the Chugoku region is mountainous and the amount of arable land per person is small, or that local governments actively supported immigration, but when I searched for something that tackled the issue head-on, I came across the "History of Migration to Hiroshima Prefecture" (general history section, data section), edited and published by Hiroshima Prefecture in 1993.

Looking at these two books, the fact that the prefecture has independently compiled the history of its citizens' overseas emigration shows that Hiroshima is an immigrant prefecture and that it recognizes the value of its immigration history and is proud of it.

To digress a little, when I go to a library to cover a region, I often come across materials related to the region. It is only then that I learn for the first time about the history and uniqueness of the region, and am struck with excitement. Everywhere you go there are corners for local materials, but Okinawa has the most extensive collection of materials unique to the region. This is probably because it has a particularly unique history and culture. Hokkaido also has materials related to the unique field of Ainu-related materials.

In that sense, it is precisely because Hiroshima Prefecture has a unique history of overseas migration that such a book was produced. Of course, in the case of Hiroshima, the most important thing is the heavy and significant history of the atomic bombing, and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum has been established to collect and preserve a vast amount of related materials.

In this way, overseas migration and the atomic bomb and war occupy a unique and important place in the history of Hiroshima Prefecture, and the two intersect at the "point" of Japan and the U.S. Kato Shinichi's history lies around that intersection.

Soil for migrant workers

Returning to the topic of the "History of Immigration to Hiroshima Prefecture," the "General History" was written by leading experts in immigration studies in Japan, and provides a chronological summary of immigration from Hiroshima Prefecture, set against the backdrop of Japan's overall immigration history, including immigration to Hawaii, North America, Central and South America, and Asia, as well as government-sponsored immigration to Manchuria.

As a prologue to this book, the author examines "the characteristics and background of immigrants from Hiroshima Prefecture." Looking at the number of Japanese immigrants overseas by prefecture from 1899 to 1932 (Taisho 13 to Showa 7), the author shows that Hiroshima Prefecture ranked first in the nation, and cites the "culture of migrant workers" as the background to this.

As far back as the "middle and late Tokugawa period," the book mentions the existence of migrant workers known as "Akimono" from Aki Province (western Hiroshima Prefecture) who had semi-specialized skills such as woodcutters, stonemasons, and carpenters, and introduces the culture of migrant work during this period, saying, "Many people from Hiroshima Prefecture, especially from Aki Province, went to various places to work..."

Next, he cites the amount of cultivated land held by farmers as the background to "migrant labor during the Meiji period." He points out that in 1885 (Meiji 18), the amount of cultivated land per farmer in Aki Province was 1 tan 10 bu, the second-lowest in the nation, and that Bingo Province (eastern Hiroshima Prefecture) was the sixth-lowest (from Huesca's "Nihon Chisanron" [On Local Production in Japan]), and that "for these reasons, migrant labor became widespread in both provinces from the mid-Tokugawa period onwards, and after the Meiji period, with the development of capitalism, this gradually changed into migrant wage labor."

As a specific example, he cited the many cases of people migrating to coal mines in Fukuoka Prefecture and to spinning factories in various regions, and said, "They were known to have excellent virtues such as diligence, thrift, and patience, and were qualitatively excellent workers." The high quality of the labor of Hiroshima people was also appreciated by the host country when they immigrated to Hawaii under government contract.

Also, as an extension of the flow of migrant workers, migration from Hiroshima to Hokkaido is said to be a precursor to overseas migration. Looking at the number of Hiroshima residents who migrated to Hokkaido, in 1882 there were 330 people, third in the nation, in 1883 there were 501 people, first, and in 1884 there were 637 people, second. However, the number has dropped significantly since 1885, due to the start of government-sponsored migration to Hawaii, where high incomes were expected, and people's destinations changed from Hokkaido to Hawaii.

Jodo Shinshu Behavior Pattern

The next reason cited for immigration to Hiroshima Prefecture is "the faith and behavior of Aki followers." Aki followers are followers of the Jodo Shinshu sect, which is prevalent in Hiroshima Prefecture. For religious reasons, the Jodo Shinshu sect does not practice abortion or infanticide to control the population. This led to an increase in population. The book describes it as follows:

"Honesty, hard work, thrift, patience, etc. were their virtues. When the population was growing but local industries were not fully developed, and the people had a hard-working spirit, they left their hometowns to go to work or become peddlers. From the 18th century onwards, people from Hiroshima Prefecture, especially Aki, migrated to various places to find work, and although they were called 'Aki-sha,' they worked honestly and diligently."

Specific examples from various regions include migration to Hokkaido, followed by migration to Hawaii as government-sponsored immigrants, and then to the mainland U.S. Furthermore, he states that religious behavior patterns have a major impact on religious activities overseas, and that one of the reasons for the success of the Jodo Shinshu mission in Hawaii is that many of the Japanese who immigrated there were from areas where Jodo Shinshu was popular, such as Hiroshima and Yamaguchi prefectures.

And as a general summary, he concludes as follows:

"Immigration is a social phenomenon that arises from a variety of complex historical factors, but it is clear that one of the reasons why the core of immigrants in Japan, especially those sent from Hiroshima Prefecture, are quantitatively large and qualitatively excellent, creating a synergistic effect between the two, is that they are spiritually based on the faith and behavioral pattern (ethos) of Shinshu followers."

Considering that migrant workers, the work ethic, and population growth (avoidance of killing) are all related to the behavioral patterns of Jodo Shinshu, it seems fair to say that the foundation of the prefecture as an immigrant town was a religious ethos. To repeat, the Kato family temple was also Jodo Shinshu.

(Titles omitted)

© 2021 Ryusuke Kawai