On 22 April 1942, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) ship the SS Princess Mary was docked at the wharf in Ganges on Saltspring Island. It was not a regular ferry run. The ship was chartered by the Canadian government to take all Japanese Canadian residents off the island to Vancouver where they would be held at Hastings Park, a temporary detention centre, before being shipped off to ghost towns in the interior of British Columbia and other points further east. It was the traumatic beginning to years of struggle in exile from their idyllic island home.

They left behind thriving farms and businesses, many of which were built up over a number of decades. For them and about 22,000 other Japanese Canadians on the West Coast, 1942 was the beginning of many hard years that did not end with the Second World War. The racist politicians who drove them from the coast after Pearl Harbor would find ways to keep them away until four years after the end of the war. Even after they were allowed to return, painful and bitter memories of being uprooted and exiled meant that few Japanese Canadians would ever move back to the places from which they had been forcibly removed. Only the Murakami family would ever return to live on Saltspring Island.

In 1954, they returned to the island with the intention of buying back the land that had been taken from them. They were unsuccessful. Despite the systemic and social racism they faced, they decided to start over. They purchased land and with relentless drive and hard work managed to once again flourish. They remain on the island to this day, steadfast in their determination to ensure that the injustices of the past are not forgotten.

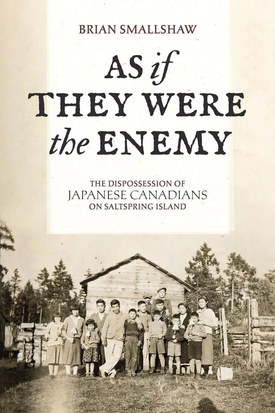

— from the Introduction, As if They Were the Enemy: The Dispossession of Japanese Canadians on Saltspring Island by Brian Smallshaw

Brian Smallshaw and his wife Rumiko Kanesaka relocated from Tokyo to Salt Spring Island in the mid 1990s, looking for a more natural environment in which to raise their young son. It wasn’t long before they began to connect with the small Japanese Canadian community on the island, numbering only six individuals at the time. Over the years the population has grown and there are now 70 Nikkei on the island, including kids born of mixed marriages, approaching the pre-war population of Japanese Canadians.

Rumiko and Rose Murakami were part of the group that created the Heiwa Garden in Ganges in 2009. During that time, Brian began to dig deeper into the story of the Japanese on Salt Spring. With his book, As if They Were the Enemy: The Dispossession of Japanese Canadians on Saltspring Island, Brian takes a deep dive into that story, peeling back layers of history, racism and opportunism to create a fascinating read for anyone interested in the history of this province.

* * * * *

Your life has followed quite a trajectory. Early on in the book you mention growing up in Saskatchewan and knowing Tom and George Tamaki. I wonder if they are any relation to Mabel Tamaki. My mother was born in Moose Jaw and Mabel was a friend of hers.

I suppose it is a bit of an unusual trajectory, from Saskatchewan to Southeast Asia to Japan to Saltspring. Yes, the Tamakis were family friends; my father worked with Tom at the Department of Mineral Resources in Regina, Tom as a lawyer and my father as a chartered accountant. I never knew George, who was part of Tommy Douglas’s famous ‘Brain Trust’, but Tom and his wife Mabel were often at our place because they and my Mom and Dad were in a number of bridge clubs, and Tom and my Dad were in an investment club together.

There was another connection too, Mabel and my Mom were high school friends. Mabel was born in Saskatchewan and her father Genzo Kitagawa owned a chain of fabric stores called Silk-O-Lina that had branches in several prairie cities and also in Vancouver I believe. Growing up I was aware of the injustice that Japanese Canadians had suffered during and after WW2, but only vaguely.

After high school I was lucky enough to be involved in two Canada World Youth exchanges, first to Indonesia as a participant, and then to the Philippines as a group leader. Afterwards, I was backpacking around Asia and ended up in Tokyo, where I taught English and began learning aikido. I had originally only planned to stay about six months, but I was hooked and ended up spending almost two years there.

I returned to Canada to continue studies at the University of Regina, but was longing to go back to Tokyo, so I applied to Sophia University, was accepted and ended up completing a degree in Sociology and Political Science at the university’s international campus.

Afterwards I spent two years in Sophia’s Japanese Language Institute working on my Japanese, and after graduation went to work for the Japan External Trade Organization editing an English-language magazine, and also worked for the Japan Auto News, a weekly digest of auto industry news for General Motors in the US.

I ended up spending another 12 years in Tokyo, all of it living within a 20-minute walk from Shinjuku Station. During that time I met and married my wife, Rumiko Kanesaka, who was working as a freelance editor and translator.

I loved living in Tokyo. Though I’ve always loved the outdoors and wild remote places, life in the middle of Shinjuku during the boom years of the 80s and early 90s was exhilarating. Tokyo was becoming very cosmopolitan, and Rumi was working for p3 art and environment, a group that managed an ‘art space’ that was created underneath a 400-year-old Zen temple in Shinjuku. We organized all sorts of art shows and events with artists from around the world.

Life in Tokyo was tremendously fun, but after I had been there 12 years we were feeling like it was time for a change. After our son Leh was born in 1994, we wanted a more natural environment to raise him than the centre of an enormous city, and made the decision to move to Saltspring.

We built a house on a piece of property that we’d purchased several years earlier and I continued working a business that I’d started about five years before, importing computer networking equipment into Japan. We’ve lived here ever since; Leh grew up as an island kid, graduated from UVic (University of Victoria) several years ago with a degree in geography, and recently was hired by Environment Canada to do GIS work.

Some of my favourite memories are fishing for bass on St. Mary’s Lake, and in fact Amy and I spent our honeymoon at a small place called Frida’s Cottage on Salt Spring. I found your book fascinating, looking at the early history of the Japanese in Canada and the subsequent dispossession and expulsion, as viewed through the history of Salt Spring island. What was the impetus to write the book?

One of the reasons we moved to Saltspring was because one of my profs at Sophia, Neil Burton, had decided to retire here. Neil was a Canadian and one of the first graduates from UBC’s China program, and after living for many years in China he and his Japanese wife moved to Yokohama and he began teaching at Sophia where I met him. He became a very good friend and mentor, and when Rumi and I decided to buy property in Canada, he suggested we look on Saltspring where he’d already bought a place.

Years later when we were all living on the island, Neil became ill with cancer and in the last year of his life I met another of his old friends, John Price who was teaching history at UVic. He asked for some help with a web project he was involved in, and spending time at the university made me realize how much I missed the academic environment. John encouraged me to take a class, which led to me deciding to do a graduate degree in history, which led to a paper on the Uprooting as it occurred on Saltspring, which I ended up expanding to become my thesis, which I then turned into this book.

I suppose the original impetus, though, was curiosity about the Japanese history of the island after moving here from Japan. Rumi became involved in the effort to create a Japanese garden in Ganges to commemorate the Japanese Canadian pioneers on the island and the Uprooting. In the course of that, we got to know Rose and Richard Murakami and heard their family’s history of being exiled from Saltspring and later return, and the fact that the largest of the Japanese Canadian properties before the war ended up in the hands of the local agent for the Custodian of Enemy Property.

Writing a paper about it for a class at UVic I started digging deeper into that history and was horrified by what I discovered. I became determined to make the story better known.

I’m curious – my inclination is always to write Saltspring Island but it most often seems to be written as Salt Spring Island, two words. You chose to use Saltspring in the title and throughout the book. Why is that?

‘Saltspring’ or ‘Salt Spring’? Ha! There has been a controversy about which is correct almost since the beginning of the colonial history of the island. Valdy, the well-known Saltspring musician, defines an island as ‘a difference of opinion surrounded by water’, and that even extends to disagreement about which is the right spelling! Both are considered correct, but I’ve seen the one-word spelling on some early nautical charts and decided that I like it better, so that’s what I use.

One of the most interesting parts of the book is near the beginning when you talk about the early history of the island, post-contact, and the ethnically-diverse makeup of the island. We’re talking about going back to 1894. It sounds like that while racism did exist, for the most part, things were relatively harmonious. Would that be a fair summation?

Actually, the ethnically diverse make-up of the island goes back to the very beginning of the island’s colonial history in 1858. Blacks from the US were among the very first settlers here. Was early Saltspring relatively harmonious? This was a question I really wanted to answer but from my research I conclude that it’s very difficult to say. There’s plenty of evidence that there was a kind of ‘frontier egalitarianism’.

The Gulf Islands are considered to be kind of idyllic now, but in the late 1800s and early 1900s life here was pretty hard and settlers trying to eke out a living on this rocky little island depended on each other for survival. Saltspring’s first schoolteacher was black. Hawaiian settlers were encouraged to settle here with land grants. At the same time, there was vocal opposition among some of the white settlers when a black settler was given a position as a policeman.

Things seemed to get worse during the 1930s. The MLA for The Islands, a Saltspringer by the name of Macgregor Macintosh, was a strident racist who gave public lectures on the island and around the province calling for the expulsion of all Asian Canadians, lectures that were apparently quite well attended on Saltspring. So I think it’s difficult to say whether it was harmonious or not; some people were racist, some weren’t, and the situation changed over time.

After nearby Mayne Island, Salt Spring had the highest ratio of Japanese to non-Japanese residents in the province. It’s astonishing to see how much property was owned by Japanese Canadians. It seems that for the most part, the community was held in high regard by other islanders. Yet when the time came for Japanese Canadians to be forcibly removed, no one stood up for them.

This was also something that I tried to grasp; why did almost nobody push back against what was done to the Japanese Canadians of the island? You’re correct: by the beginning of WW2 the Japanese Canadians of Saltspring were doing well and their prosperous market gardening operation clustered around the end of Booth Canal were an important part of the island’s economy, shipping sizeable quantities of food to southern Vancouver Island and the mainland.

They were clearly a well integrated part of the community and they had some influential allies, such as Dr. Rush, the island’s doctor, who stood up at one of Macintosh’s meetings to dispute what he had to say. Yet almost as soon as the Japanese Canadians were taken from the island their properties were basically looted and nobody did anything about it.

It didn’t have to be this way; on Bainbridge Island in Washington, a fairly good American analogy to Saltspring, the property of Japanese Americans was cared for during the war, and a large proportion of them returned afterwards and resumed their previous lives. I attribute the difference to the fact that they had some strong local allies, the American government didn’t sell off their property, and they were allowed to return to the coast at the end of the war, instead of 1949 as was the case in Canada.

You give a lot of emphasis in the book to the wartime dispossession and fight for fair compensation. Was there anything that stood out for you?

In researching Iwasaki’s court case to get fair compensation for his property I dug pretty deeply into how the government came to the decision to sell off Japanese Canadian property and the legal mechanism that it used to do it. Among scholars of the Japanese Canadian uprooting there is a consensus that what was done was unmerited, unjust and even immoral, but I actually go further—I think it was illegal. While most historians condemn what the Canadian government did, they believe it cannot be legally challenged because it was done while the War Measures Act was in force.

In my view, however, the War Measures Act changed how laws and regulations were enacted—without the oversight of Parliament—but it didn’t alter the fact that the country still operated under the rule of law. The government didn’t govern by decree, its actions had to be supported by laws and regulations. The politicians and government officials of the day were fully aware of this and Order-in-Council 469 that ordered the sale of Japanese Canadian property was given under the authority of a government regulation concerning the handling of enemy property, and concluded with the words:

“…and for the purpose of such liquidation, sale or other disposition the Consolidated Regulations Respecting Trading with the Enemy (1939) shall apply mutatis mutandis as if the property belonged to an enemy within the meaning of the said Consolidated Regulations.”

The authority for this order rests upon a regulation with a very clearly defined scope: enemies. It was being applied to Canadian citizens as if they were the enemy (hence the title of the book). The action was outside the scope of that regulation, or ultra vires, to use the legal term. It was a legal sleight of hand to give a veneer of legality to the use of a regulation pertaining to the handling of enemy property, to that belonging to Canadian citizens. I am not a lawyer, but I cannot believe that it is legal to apply a law for enemies to Canadian citizens.

It’s clear from your book that there are lasting scars left on the Salt Spring Island community by what transpired during and after the war. How is your work being received on the island?

I’ve been happily surprised by the reception the book has been receiving, especially here on Saltspring. There were a lot of myths floating around about the events during and after the war and there has been some push-back from families that benefited from the sale of Japanese Canadian properties, but it seems that research on primary sources has put most of those old tales to rest.

The book has been very positively received by the Japanese Canadians of the island, a community that has grown substantially since our arrival a quarter of a century ago, though it is still less than the 77 who lived here at the outbreak of the war. Many of them are Issei curious about the people that came before. Most of all, the book was written for them.

*This article was originally published on The Bulletin: A Journal or Japanese Canadian Community, HIstory, and Culture on February 6, 2021.

© 2021 John Endo Greenaway / The Bulletin